The case of Saint Regis University (SRU), an online distance-learning school which between 2002 and 2004 held recognition by the government of Liberia, is uniquely complex and problematic in the study of transnational education and the questions of legitimacy and authority that it raises.

The case of Saint Regis University (SRU), an online distance-learning school which between 2002 and 2004 held recognition by the government of Liberia, is uniquely complex and problematic in the study of transnational education and the questions of legitimacy and authority that it raises.

SRU was a radical and iconoclastic interloper in the higher education establishment. It was established by the owners of a successful trade school and brought the direct, no-nonsense approach of a trade school to the university sector. It did not so much challenge academia as threaten to destabilize it altogether. In the middle-class circles of university education, SRU was a blue-collar outsider not inclined to mind its manners. SRU was hugely successful, with many satisfied graduates, and made millions of dollars. It also made some extremely powerful enemies, determined not only to close it down but to demonize everything it had stood for.

In 2004, SRU found itself denounced by its opponents as a diploma mill in US Congressional hearings, with no right of reply and no attempt at a balanced presentation. Subsequently, the United States government let it be known to the Liberian Ministry of Education that if it did not withdraw support for SRU, US funding to the Ministry might be withdrawn. Mired in legal troubles. SRU closed in late 2004. Then, in 2005, criminal charges were filed against eight US citizens involved in the operation of SRU. All eight subsequently pleaded guilty, thus meaning that no trial took place and many of the most significant arguments surrounding the case were not tested in court.

There remain troubling questions about the role of the US government in the whole saga. The case itself raises serious issues of bias and due process. Its conclusions have also been subject to a great deal of politicization, both by the media and by the education establishment.

In the discussion below, I intend to tell the story of SRU, focussing on the following issues:

- What was SRU’s educational methodology?

- Was the claim by SRU that it held accreditation from the government of Liberia true, and if so, what did this accreditation mean?

- If the accreditation claim was true and meaningful, to what extent were degrees issued by SRU (a) legal and (b) legitimate?

- In the light of the above, what approach should be taken towards the many individuals who obtained degrees from SRU?

1. The birth of a revolutionary idea

The principals behind SRU were a married couple called Dixie Ellen Randock and Steven Karl Randock from Spokane, Washington. Before starting SRU, Dixie Randock had started and grown a real estate school to a position of significant success. She was smart, ambitious, single-minded and dedicated to making SRU a revolution in online schools. She was the educational mastermind behind what would become SRU, while Steve Randock handled the finances.

Dixie recalls,

I attended college quite a few years and was a very successful real estate broker with multiple offices and member of Spokane Club, Country Club, etc. My husband and I were millionaires long before ever starting SRU, had very successful businesses and exceptional reputations.

It was after we were embezzled [by their former accountant, who went to jail as a result] that I began putting together SRU, even though I had thought about it for a few years prior. The embezzlement of what police said was $600,000+ (actually much more) caused me to close my brokerages in WA and ID, although I kept the real estate/law school open. I had written all the State approved texts and courses for these schools myself, which are still in use in the school and other colleges to this day.

In 1999, Dixie had branched out and become the proprietor of AdvancedU.org. This offered degree programmes by using life experience credit. It asserted, “Our Evaluation & Endorsement Advisors evaluate and match your life experience with traditional college curriculums to provide you a wide variety of 100% verifiable degrees, certifications, credentials, designations and awards for “self-made” and “self-taught” experts in all fields. No classes or attendance is required, because this is NOT a school. Unlike school programs, The Evaluation & Endorsement Program is an evaluation process, which is done by only a few specialized organizations.”

The Evaluation and Endorsement Program used a concept described as “peer evaluation”, conducted by a “peer advisory” and administered by the Evaluation & Endorsement Peer Advisory Trust. By 2001, the evaluation body had developed into the Advanced Education Institute Trust (AEIT). The peer advisory idea was radical, for it suggested that rather than assessment being conducted by individuals of higher status than the candidate (as in traditional academia), it would actually be conducted by peers of similar status. Cohort or peer assessment had precedent in short-residency non-traditional mainstream programmes such as the University of Phoenix, and also at the Union Institute, whose doctoral committees were composed not only of mentors but also of peers. The Trust said of its process,

Our clients describe accreditation by their peers as the ultimate validation of their own knowledge and achievements, and their credentials as extremely valuable and proven in enhancing personal careers, gaining confidence to increase earning potential, improving self esteem, and heightening recognition, respect and appreciation by others.

Clearly, peer evaluation was a radical and nontraditional statement of educational philosophy – effectively asserting that any person who had received the proper training could be competent to recognize educational achievement gained through life experience and to map it to a degree curriculum. It also avoided some obvious problems in recruiting faculty. The faculty and doctoral graduates of mainstream universities were unlikely to have specialist expertise in experiential credit assessment or to be sympathetic to its revolutionary implications, rendering them unsuitable for appointment. Dixie said,

I researched the many ways available to earn college credits through an evaluation process of experience, self-study, independent studies and research, etc. I collected and studied the processes (e.g.; x years practical experience equaled x credits) and began creating a sort of matrix for our advisors to use that closely matched US and European universities.

Although not all our advisors held mainstream degrees, they did understand the equivalency matrix and also had access to sources when the credit might be given for research, dissertations, other papers, or independent studies.

The Trust made it quite clear that what was being offered was a non-traditional challenge to the mainstream.

This is a unique process, established for deserving individuals who for one reason or another did not obtain a degree in the traditional fashion.

Even the most stringent educators are coming to the realization that in today’s information age, an individual can reach and surpass college graduate levels of knowledge without ever stepping inside a “brick and mortar” classroom.

Many talented, intelligent, and creative individuals have attained more education than a college graduate by self-teaching, and learning through their own research, practice and work experience.

It is common knowledge that many of our world’s most innovative pioneers in technology, science, and practices belong to this group of individuals.

However, most universities arrogantly insist that you can ONLY attain a degree level education by enrolling, paying and attending a college for years.

Perhaps this thinking is meant to prevent a perceived conflict of the school’s own best interest, in that granting a degree to a self-educated person may take away tuition that might have otherwise been paid to the school.

Initially, AdvancedU.org awards said on the diploma that they were not degrees, and that the Evaluation & Endorsement Peer Advisory Trust was “a process, not a school”. Nevertheless, the market was looking for a product that would fit into the mainstream of credentials, and that meant awards that were described as degrees and, if they were not actually to be issued by schools, at least used names that were similar to schools. As of 2000, the website stated,

These are NOT schools, and they should not be confused with the names of any University. Please let us know which Peer Advisory Program name you prefer. You may choose from any of the Peer Advisory Programs:

Holy Acclaim University, Saint Lourdes University, Holmes University, Cathedra University, Audentes Technical College, Concorda Graduate Institute, Saint Concordia University or Valorem University.

Peer Advisories are assembled into groups of individuals who are considered to be experts in their subject areas.

These lines came to be further blurred, however. A year later, the same section read:

You may choose from many established Peer Advisory names, or you may choose a Custom Name. A custom name is any name that you choose or create and is not in use by an existing, accredited university or one that would infringe upon registered trademarks, symbols, etc. [A link was provided to unavailable names that were members of the Collegiate Licensing Company]

To view a list of names that AVAILABLE names that are no longer used, and are available, click the link for a list of Closed Universities & Colleges.

It must be stressed that the Academic Peer Advisories use words including “college”, “university”, “academy” etc., not as nouns, but as the lexis in their descriptive titles. The names are titles of Academic Peer Advisories, NOT schools. The programs do not offer courses or classes and are not for those who are beginning or continuing their academic education.

Viewed with the benefit of hindsight, this justification was too subtle a distinction to be grasped by most consumers. Documents that were the result of the peer advisory process continued to bear the seal of the Trust, and were worded so as to state that it was the awarding body, but started also to bear the names of genuine schools when these were chosen as Academic Peer Advisories. Moreover, they could be verified by the official verification centre (also maintained by AEIT) in whatever institution’s name was on the certificate.

While this might be ethically problematic, it was not a legal difficulty – at least not for AEIT as the issuing body, since there was no law against doing this in either Washington or Idaho. The documents from AEIT presented as exhibits in the SRU case are not similar to those provided by “replacement diploma” or “fake diploma” services that mimic the look and the signatures that appear on actual diplomas issued by the schools in question. Rather, they all use an identical and distinctive typeface and format. They bear the AEIT seal and state that the awarding body is “The Regents of the Evaluation and Endorsement Advisory and the President and Chief Provost” Other wording states, “Be it known that knowledge and proficiency has been demonstrated by completing and satisfying all requirements of the Regents of the Evaluation and Endorsement Advisory”. One transcript using the peer advisory name of “University of Maryland” gives Dominica as its address. The documents might well have produced confusion, but a straightforward reading would be unlikely to give the impression that they had been created to deceive.

At AEIT, as would be the case at SRU, each candidate was assigned an advisor for the duration of their programme. These peer advisors carried out assessment of the candidates and assigned credit to them. They had all received a full training programme and were equipped with a kit consisting of hundreds of electronic letters that were scripted responses to likely enquiries. Where an issue arose that they could not handle themselves, they would pass this on to senior management.

Peer advisory degrees could be backdated. The rationale was that if the applicant was qualifying on the basis of their experience, then their degree would logically have been earned at the point in time when that experience had reached the level required by their degree, rather than at the point when it was presented for credentialling,

Your degrees and transcripts will be dated as closely as possible to the time that you attained your education.

For example, if you reached a Bachelor Degree level education (without attending classes) by 1996, we recommend that your degree be dated no earlier than 1996. Then, if you attained a Master Degree level education by 1998, your degree should be dated 1998 or later, and so forth as your education level increased up to a Doctorate level.

The peer advisories allocated experiential credit by creating formal transcripts listing coursework that, according to them, were comparable to the applicant’s experience. These transcripts were based on the standard degree curriculums of mainstream universities. The final result did not indicate that credit had been earned through experiential assessment, and simply gave a list of courses, credits, grades and a grade point average.

Transcripting experiential credit in this way was in keeping with the practice of several mainstream schools that granted credit for experiential learning. For example, Charter Oak State College in Connecticut (www.charteroak.edu), a regionally accredited US institution, had at that time (and still has today) a bachelor’s degree programme in which it is possible to submit a portfolio of experiential learning credit to challenge a wide variety of courses that would otherwise be completed via examination or coursework.

In addition, applicants could transfer credit into the AEIT programme from other universities, which was permitted without limits on the age or amount of credit that could be transferred in. Many other institutions place artificial limits on credit transfer in order to compel the student to take a minimum number of credit-bearing courses with their school, irrespective of whether such a learning experience is academically necessary from the student’s perspective.

As was explained,

…you will receive transcripts for each degree, showing representative courses that correspond to your experience as compared to a traditional classroom setting. The transcripts show a traditional curriculum of courses that are the equivalent of the skills you have acquired as though you attended. There is no mention of “equivalency”. The dates and grades and grade point average will appear.

An enormous amount of research and labor is required for each individual transcript. Transcripts are carefully compiled to match the candidate’s qualifications and education.

Based on the educational information and description of experience supplied by the candidate, the peer advisory can determine if the candidate’s knowledge level is on par, or exceeds that of a college graduate.

When the advisors are not provided with certain information, or if the candidate cannot provide information concerning former grades or other documentation, the advisory will make their judgment based on the available data and their own research.

When the candidate does not provide grades, the advisory may also make their own recommendations as to grades in each course, based on whatever information the candidate has provided.

There was also significant input from the candidate, who was expected to self-evaluate as part of the process:

…we always provide the candidate with a “proof” of the transcript and other documents, before original documents are produced.

When your “proof” is emailed to you for your approval, you may request changes to ensure accuracy. You may also submit your grades and other documentation at the same time of your acceptance.

We welcome and encourage your participation in the selection of representative courses that best fit your skill levels, as well as your overall and specific grades.

Your original transcript will not be completed until you are completely satisfied and have given final approval.

If you feel that certain courses (or degrees) do not fit your skill level, please let us know.

Your peers will review your data and based upon the certain criteria, they may either replace courses with those you recommend, or our advisors will research other representative courses (or degrees) to better match your circumstances.

If you wish for the advisory to modify or replace courses, please and identify the courses and provide additional as to your strengths.

Self-evaluation is again a concept encountered in non-traditional education, usually as part of a philosophy of democratization and a critique of educational hierarchy. To do this outside of a school setting is reasonably widespread. To do it as part of a process leading to the award of a degree would be an open challenge to traditional academia.

2. St Regis becomes a Liberian university

The success of AEIT made it clear that there was significant demand for experience-based credentials from a school that was real and verifiable. The next step would be to create a legitimate online university targeting working adults and offering degrees at all levels via an accelerated experiential assessment at low cost, and Saint Regis University was designed specifically for this purpose. As of 2001, SRU was one of the AEIT peer advisory names that could be used on peer advisory degrees. Later that year, it developed an independent life of its own. While its website did not include much of the information about the peer advisory process that had appeared at AEIT, the concepts and methodology were the same.

Institutions that award college credit based on the assessment of experience gained outside a formal classroom setting (referred to as the accreditation of prior learning (APEL) or prior learning assessment (PLA)) are engaged in the most revolutionary aspect of non-traditional education. College credit for experiential learning democratizes education by changing the role of the university from education provider to education assessor. It is this process, when used by schools outside the mainstream, that is most vociferously attacked by mainstream advocates, because it poses the greatest threat to the mainstream. It offers the prospect of radically cutting the duration, resources and cost of degree programmes in many areas for experienced adults, and when allied to distance learning methodologies, can potentially be expanded to meet an international market. In a key example of disruptive innovation, the non-traditional movement pioneered experiential credit as early as the nineteenth-century. Gradually, the mainstream took on elements of APEL, though still with obvious resistance to the ideology, and in a patchy manner that has left areas such as graduate-level credit poorly served. That particular market niche then became a focus for a number of non-traditional schools working outside the mainstream.

There had been “assessment universities” before SRU. One of the leading examples was the former Summit University of Louisiana under the late Raymond Chasse. Summit was a genuinely alternative distance learning school operating outside the accredited sector. At Summit, experiential learning received full credit and adult learners were placed in charge of their degree programs. Summit in turn was an extension of the University without Walls project that had begun in California in 1974 under the late Melvin Maier Suhd. Eventually, Summit and most similar schools were driven out by legislative changes. Even with the significant respect in which Suhd was held as an educational theorist and humanitarian thinker, Summit had faced constant battles with the education establishment and the lawmakers who were protecting that establishment. What they did was considered not to look like a university, nor to behave like one. It was determinedly alternative and challenging, in an area that promotes conformity – through the standardization process that is accreditation – and fears substantive change.

Ray Chasse also founded a very similar school to Summit called American Coastline University, and ran the two in parallel from his home in Louisiana. While Summit closed, American Coastline survived for a time after Chasse’s death.

When SRU first appeared online in late 2001, it asserted that it was chartered in the Commonwealth of Dominica and also derived authority from being a branch campus of the International University of Fundamental Studies in Russia (as did American Coastline University). It also cited a number of accreditations from private bodies (which did not hold government recognition) which also accredited American Coastline University. Dr Richard J. Hoyer of American Coastline University served in an uncompensated role as Provost of SRU between February and October 2002.

While its Dominican corporation would be maintained behind the scenes, this period, however, was to be brief. Clearly, it was impossible for SRU to become accredited by the conservative accrediting associations in the USA, which were extremely hostile to experiential credit for degrees. The question was then, what would be an acceptable foreign alternative? Accreditation by a national government was held by key authorities in the USA – foreign credential evaluators – to be the equivalent of recognized US accreditation. Well-known distance education author John Bear had devised the concept of GAAP – generally recognized accreditation principles – and said that for non-US schools, this meant, “recognized by (or more commonly a part of) the relevant national education agency”. Moreover, “schools the agency accredits are routinely listed in one or more of the following publications: the International Handbook of Universities (a UNESCO publication), the Commonwealth Universities’ Yearbook, the World Education Series (published by PIER), or the Country Series (published by NOOSR in Australia).”(1)

The search was therefore on for a national government that would be prepared to support SRU and grant it accreditation. Dixie said of this,

“I chose Liberia, for many reasons, one of course because they are English speaking, their constitution was very close to our US constitution, many laws are similar, and I had an idea they may be open minded as to how any person may earn a degree. It may be that many Liberians are uneducated, but there were and still are many highly intelligent people with drive and ambition, whose actual education levels are on par with those in the US and other countries with college degrees. But, these people had little to no chance of ever moving up without any documentation or evaluation of their knowledge.”

Other American non-traditional providers had also sought a home in Africa. At one time the largest non-traditional distance learning university in the USA had been Columbia Pacific University of California, which was closed in that state in what many saw as a politically motivated process. A successor institution, Columbia Commonwealth University, had sought and gained accreditation from the African nation of Malawi in 2001, and continued to offer programmes to American students on the basis of this status. Another non-traditional distance learning university offering programmes to an American as well as international base, Adam Smith University, had been established by an act of the legislature in Liberia in 1995.

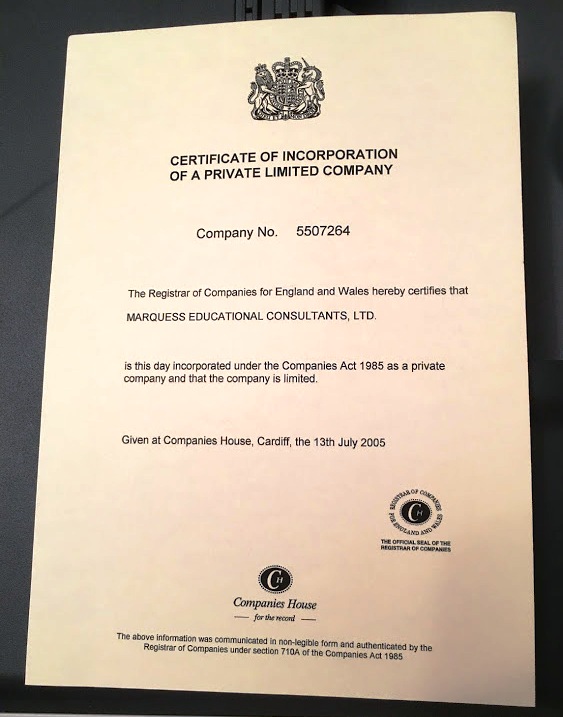

On 12 June 2002, the National Board of Education, Inc., was incorporated as a non-resident domestic corporation in Liberia with its registered address as 80, Broad Street, Monrovia. The directors were listed as F. Derradji, C. Dreyer and M. Fuchs, all of the aforementioned address, with Derradji the sole shareholder. This corporation was to be the legal owner of SRU in Liberia.

Around September 2002, all mention of Russia and Dominica was removed from the SRU website and it was asserted that SRU was chartered and accredited by the government of Liberia. Specifically, the following claim was made:

“St. Regis University was originally Chartered January 10, 1984, Created by Decree of the People’s Redemption Council Government of Liberia, as a private school with a physical campus. In 1998, St. Regis University closed the physical campus and moved to a virtual location to better serve students by offering affordable programs without sacrificing quality, and began a four year accreditation process toward formal recognition.

(Prior to 1998 no process existed for the accreditation of online universities.)

On August 28, 2002, St. Regis University completed all accreditation requirements and received formal recognition by the Higher Education Commission of the Education Ministry of Liberia as a legal, valid and authentic university, operating under the authority and in conformity with all current laws and regulations ruling educational competency certification of the Republic of Liberia. The Higher Education Commission of the Education Ministry of Liberia is solely responsible for granting recognition to post-secondary education institutions in Liberia including St. Regis University, University of Liberia and Cuttington University College…

St. Regis places less emphasis on “systems” and more emphasis on “outcomes”.

St. Regis University has submitted documentation of degree programs, descriptions of course/course equivalency completion, curriculum, catalog, assessment manual, policies and all required criteria meeting the very high standards required to gain recognition by the Education Ministry of Liberia.”

(Source: http://www.saintregisuniversity.ac/accreditation.htm as retrieved on 2 December 2003)

What had happened was that the NBOE had purchased a semi-defunct school in Liberia and renamed it St Regis University. According to Dixie,

The Liberian government was eager to work with us, and it was they who recommended that we buy an existing accredited school (accredited in 1984) to become established.

The school was in Monrovia, the same building as the Liberia Department of Education, and had a small staff and phone system, but because of the ongoing war, there were no longer any students or teachers. But our intention was never to teach, but to offer online equivalency programs. So, we agreed to keep the small staff and equipped it with computers/servers, filing system and used the school in the beginning, as a base. They told us we could change the name, which we did, paid all back fees and taxes owing plus accreditation transfer, keeping the original accreditation date.

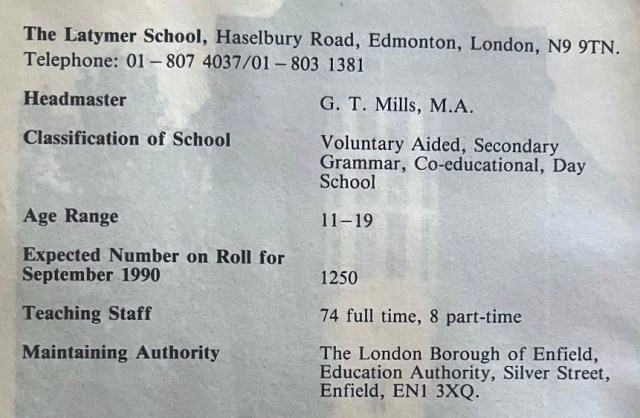

Aside from all the other costs, the accreditation for SRU had cost a mere US$300. The school had originally been named after James Monroe and was owned by the mother of one of the Liberian officials, possibly Dr Lawrence Bestman. Before long, the Randocks bought a second school, named after Joseph Jenkins Roberts, which had been accredited in 1982. The Liberian Ministry of Education suggested that this should be renamed Robertstown University.

It was news to many that SRU had had any existence in Liberia in the 1980s (albeit under a different name) before it first appeared on the Internet as a Dominican entity in 2001. However, even SRU’s harshest critics acknowledged that this was the case at that time.

“George Gollin, a professor of physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has researched Saint Regis University and “diploma mills” like it. Despite its claims to Liberia, he says the school is based in the United States, and has a network of more than 100 Web sites. “These were real schools in Liberia, but they folded in the ’80s,” Gollin said.”(2)

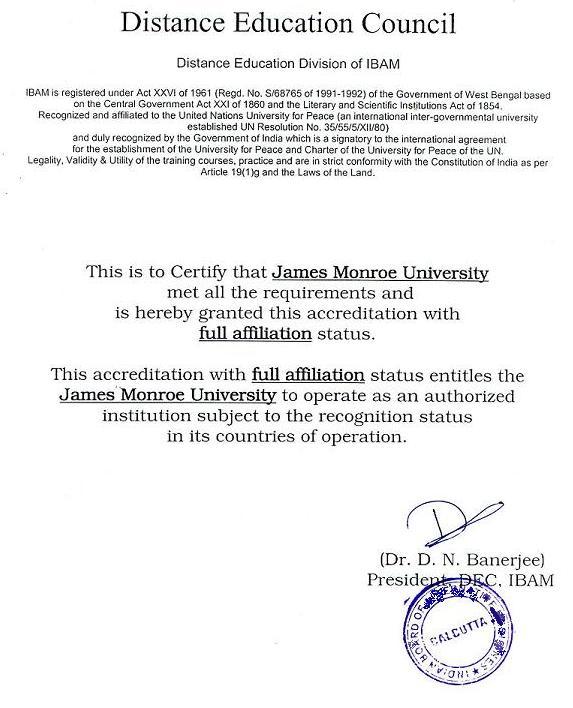

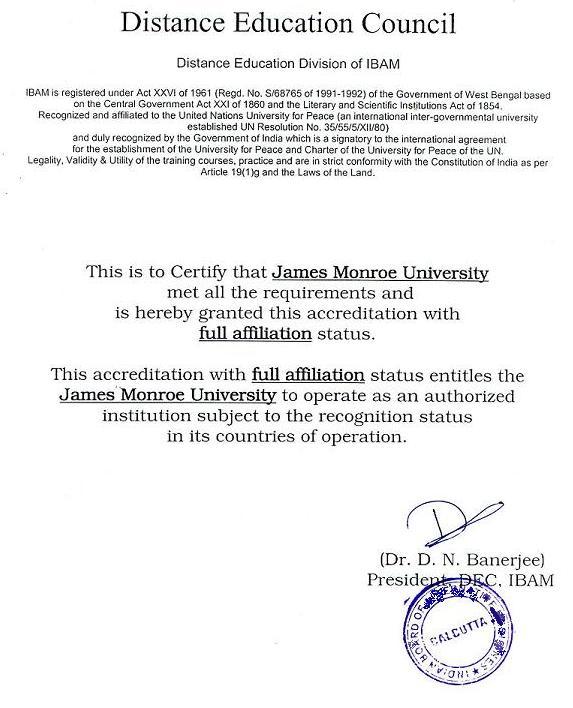

In support of the accreditation, a number of documents were made available to enquirers. The first of these was an accreditation certificate issued by the Liberian Ministry of Education to the National Board of Education, Inc., as operator of SRU, and signed by two officials, supplemented by a document giving further particulars.

A further, similarly worded certificate would follow, signed by Dr Lawrence Saydee Bestman, the Executive Director of the National Commission of Higher Education of Liberia:

The motto adopted by the Minister of Education was “Accelerated Education for Accelerated Development”. This would exemplify the synergy between SRU and the Liberian government. As it emerged from the destruction of civil war, Liberia saw there was an urgent need to expand its higher education sector and to embrace new technologies such as distance learning and experiential assessment in order not only to meet its domestic needs but to compete internationally.

Before long, SRU acquired an official .edu.lr suffix, and its main website became saintregis.edu.lr. The .edu.lr domain was restricted to institutions with official standing as a recognized Liberian educational entity.

Gaining recognized accreditation transformed SRU. Its initial home in Dominica had offered legality, but not the acceptance that would come with government accreditation. Liberia offered membership of the cartel of accredited institutions, and a route into the acceptance that came with being part of the academic mainstream. It was a step that few other experience-based universities had previously made.

In addition, there was a market for a whole range of ancillary services. During the 2002-05 period, the Randocks not only operated SRU but a vast range of other websites, not only of other online universities but offering accreditation (through the National Board of Education, SRU’s parent body – this was available for $50,000), turnkey online universities for entrepreneurs, apostilles, an association and journal for online universities, credential evaluation and degree verification services.

Student enquiries started to pour in from around the world. Suddenly, what had been a small-scale family-run enterprise was making millions of dollars. The Randocks were unapologetic about making money. They marketed SRU with great energy and complete confidence. However, there was more to SRU than simply the drive to profit. Its success was because it was meeting market need head-on, and in doing this it was also serving to promote experiential and non-traditional education to those who would not previously have considered them.

Because so many requests for verification of SRU’s accreditation were being directed to the Liberian government, SRU made arrangements with members of the Liberian diplomatic corps and Ministry of Education staff whereby they would be paid a retainer in order to answer questions and verify the accreditation when needed.

On 13 September 2002, some two weeks after the accreditation documents were issued, Liberia’s National Commission on Higher Education published a National Policy on Higher Education:

>>National Policy on Higher Education in the Republic of Liberia (13 September 2002)

The National Policy defined the process for creating new universities thus:

The National legislature has the statutory authority for chartering institutions of higher learning only following recommendation from the National Commission of Higher Education.

The process for accreditation was described as follows:

The National Commission of Higher Education will evaluate the missions, objectives, academic programs, physical resources, finances and qualifications of administrative and instructional staff of an institution of higher learning and subsequently accredit the same. Physical resources will include campuses, classrooms and office furniture, libraries. adequate and relevant books, instructional material, laboratory equipment, conductive working environment, safe drinking water, electricity aid sanitary facilities. Evidence of accreditation will be the issuance of a certificate of accreditation by the National Commission of Higher Education or use of another official instrument by the Commission to be considered a legal document of permission to operate.

Further provisions of the National Policy dealt with financing, curriculum and the other expected aspects of tertiary accreditation. It certainly gave a clear impression that Liberian accreditation involved the operation of meaningful standards and was not merely a rubber stamp. However, SRU had been accredited just before the issuance of the National Policy.

3. SRU’s educational processes

SRU offered several routes to a degree. As of 2003, these were listed as “assessment of knowledge; “testing out” (summative examinations); Independent Study – Thesis Research; Transfer of Credit; Coursework”. A number of alumni dissertations and theses were placed online; these included some accomplished work as well as some that would admittedly have been unlikely to have met the standards of a recognized US university. Some graduates were also known to have completed a coursework route to a degree.

The majority of degrees, however, were awarded by assessment of the applicant’s prior education and experiential learning. Up to 100% of a degree could be earned through the submission of prior learning and experience, including at the masters and doctoral levels. These processes were explained at length on the website with examples of the conversion of experience to college credit.

This was followed by a series of detailed breakdowns for a number of common degree programmes.

This was followed by a series of detailed breakdowns for a number of common degree programmes.

Concerning what was required of the applicant, SRU said,

These are general principles for conducting assessment.

Apply online for a FREE Evaluation Include your resume/CV and references.

It is rare, but occasionally applicants qualify using through assessment alone (Pre-Approval). But, more often additional credit is required which can be earned through instructions/guidelines provided by the Assigned Professor. (Conditional Approval).

Applicants will be emailed a notice of either Pre-Approval or Conditional Approval. If the applicant receives Pre-Approval he/she will be give directions for acceptance and payment of graduation fees.

If the applicant receives a Conditional Approval, he/she will also receive details about the ways to proceed to meet the desired degree graduation requirements.

The applicant’s evaluation results, resume/CV will be assessed and validated by the assigned Professors and an evaluation results report will be emailed.

Once the applicant has received the required credits for graduation, he/she may accept the degree by paying the proper graduation fee.

If the applicant’s scores and assessment do not meet the number of credits required, his/her assigned Professors will suggest courses, alternative learning sources and/or supplemental submissions to complete the graduation requirements.

Also,

Send us your resume, CV, thesis, and description of your skills and experiences for a FREE EVALUATION. Your appointed advisor will compare your knowledge to levels of education required in traditional college curriculums.

The application form allowed the applicant to submit a resume, but in addition they were asked in a section allowing for free-form text (which could be added to by email if needed) to,

Please describe your life and work experience, and/or qualifications, and/or other education you have acquired, and/or any other justification you feel is important and should be considered by your advisor in your evaluation for credit.

Two references were also required. One notable omission was that there was no attempt to verify the identity of the applicant through examining official identity documents. This would prove a costly error in the light of subsequent events.

SRU’s failure was not in its willingness to promote experiential college credit or boldly to proclaim it the direct equivalent of a traditional curriculum. That process won it friends and supporters, including me, among those who favoured that methodology and who wanted to see it furthered, as well as enemies among those who wished to see it curtailed. Too often, the attacks made on SRU graduates were the result of envy and resentment from those who were unshakeably wedded to the time-serving vision of university education, and could not accept that someone might have gained experience that was judged to be the equivalent of many hours of classroom instruction. For them, it was “unfair” that SRU graduates had qualified for degrees by APEL assessment rather than doing college “the hard way”. They privileged processes over outcomes, and their outrage was easily manipulated by the media and opponents of SRU.

3. Recognized American academic authorities that accepted SRU

When some enquirers made contact with SRU from mid-2003 onwards, they were given a file of documents that indicated wide acceptance of SRU in the United States academic community. Firstly, there was a series of letters and faxes from accredited United States and Canadian universities. Secondly, there was a series of evaluations from foreign credential evaluators in the United States.

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Vanguard University, California

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by the University of New Orleans, Louisiana.

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Tufts University, Massachusetts

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Northern State University, South Dakota

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Lasell College, Massachusetts

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Florida Metropolitan University

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Eastern New Mexico University

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Emerson College, Massachusetts

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by Concordia University, Wisconsin

Acceptance of an SRU degree for graduate study by the Canadian School of Management, Ontario

Foreign credential evaluation of SRU degree by SDR Educational Consultants

Foreign credential evaluation of SRU degree by Lincoln International Educational Associates. It is not clear how they determined that SRU was founded in 1947!

Foreign credential evaluation of SRU degree by Foreign Consultants, Inc.

Foreign credential evaluation of SRU degree by AUAP Credential Evaluation Services

Foreign credential evaluation of SRU degree by the American Evaluation Institute

With respect to the universities, it should be noted that detractors of SRU, notably Dr John Bear, commonly used to ask its defenders to produce just one accredited university that would accept its credits or degrees. It will be clear that there were, in fact, several, and there were others besides those that have been documented above. Directly such information was made public, however, it would lead to the targeting of the institutions concerned by those opposed to SRU in a bid to reverse the situation; it is doubtful that any of the universities above were still accepting SRU degrees beyond 2003. For example, the University of Connecticut’s response to a SRU graduate’s admissions enquiry was made available on the web in April 2003; it is reproduced below:

After Bear contacted the author, however, things changed:

[Bear] Following an inquiry as to whether Ms. Balinskas had in fact written this memo, and whether her office did, in fact, accept the degrees of St. Regis University, Ms. Balinskas replied as follows:

Date: 2003-04-30 17:36:33 PST

“I have gone back through my e-mail archives to try to find the original question regarding St. Regis. All I was able to find was this e-mail that was written after I faxed back the response to the question. As is evident, the Subject of this e-mail was Bachelor’s Equivalence in general, and not St. Regis. I am truly sorry for this misunderstanding.

My information indicates that there are two national academic bodies in Liberia authorized to accredit educational institutions: the Ministry of Education and the Liberian National Commission for Unesco. There are only 2 institutions recognized by these bodies as legitimate: University of Liberia and Cuttington University College. I also have an e-mail from an educational advising assistant at the U.S. Embassy in Monrovia, Liberia that the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Univ. has the approval of the Ministry of Education to operate in Liberia. Unless there are other (more recent than my references) educational institutions that have been LEGITIMATELY ACCREDITED we would only consider applicants from the institutions I have listed above.

Marylou Balinskas, Director, Graduate Admissions

University of Connecticut, 438 Whitney Rd. Ext. Unit 1006

Storrs, CT 06269-1006, E-Mail: mary.b…@uconn.edu

Phone: (860) 486-0988, Fax (860) 486-6739″

(https://groups.google.com/d/msg/alt.education.distance/Gsyq62KOjYE/mnoDHFjdZ_kJ)

It will be obvious that this response was at complete variance with the memo; it was also factually incorrect, in that the Liberian National Commission for UNESCO never had any role in the accreditation of educational institutions. But the strategy for SRU’s opponents was clear and proceeded by several steps:

- challenge SRU to produce any accredited US university that had a policy of accepting its credits, and use the lack of the same to make a case that SRU was not legitimate.

- contact any school that did appear to accept SRU and supply negative information concerning SRU to it, including discrediting its accreditation, possibly even with a threat that any school accepting SRU would be reported to its accreditor.

- produce a public response from the school that stated that, despite any document to the contrary, it never had and never would accept SRU.

This activity further inflamed the conflict between SRU and its opponents.

The positions of foreign credential evaluators changed, too, though this was prompted more by the 2004 disclaimer (that will be discussed below) and negative publicity. The former American Evaluation Institute was the last evaluator known to accept SRU degrees and was still doing so at the point of SRU’s closure.

There were several cases of SRU graduates being accepted to postgraduate degree programmes at accredited universities in the USA and elsewhere, and going on to complete those programmes successfully. They were the fortunate ones. Other postgraduate students were targeted and expelled from their programmes once activists had seized on their SRU degrees and made trouble for them.

4. SRU and the Liberian government

The Second Liberian Civil War had reached a point of relative stability by September 2002 when the government lifted the state of emergency in Monrovia. 2003 started quietly but then degenerated into further fighting in March. At this stage the USA and others exerted pressure to bring about peace talks. These took place in Ghana from June 2003 and after US forces had ended the siege of the capital in July, President Charles Taylor agreed to resign in August. This was not the end of hostilities and conditions in Liberia continued to be hazardous and characterized by violence, shortages, and poverty. Amid this situation, members of the civil and diplomatic services went unpaid for long periods of time.

SRU was in touch directly with President Charles Taylor both by phone and email prior to his resignation.

SRU was represented at the peace talks in August by Richard Novak, its Executive Vice-Chancellor, who travelled from his home in the USA with Abdulah K. Dunbar of the Liberian Embassy in Washington, D.C. As a result of SRU’s representation at the talks, the Liberian Embassy in Ghana agreed also to act as a verification source for the accreditation and status of SRU, with the contact details of the Chargé d’Affaires, Andrew Kronyanh, being listed on the SRU website. In addition, Novak met with Kabineh Ja’neh, who would be appointed Minister of Justice in the new administration, and who was supportive of SRU’s educational mission. A group of SRU’s alumni had expressed a wish to assist Liberia in its reconstruction efforts, and it was put to Ja’neh that the funds alumni had raised could be used to set up a scholarship fund for students at the University of Liberia, which had been largely destroyed during the fighting. Ja’neh informed Novak that the Ministry of Education would be the responsible body for any such arrangement. An agreement for the acceptance of academic credits was also to be negotiated by Ja’neh between SRU and the University of Liberia in 2004, but this was not concluded. A similar credit agreement with the African Methodist Episcopal University had been mooted in 2003.

At the Liberian Embassy in Washington, D.C., there was confusion for a period in 2003 as to who was in charge between Abdulah Dunbar, the First Secretary and Consul, and his rival Aaron Kollie, who as Chargé d’Affaires was head of the mission. Dunbar had come to the embassy in the 1990s under the Tolbert administration and was opposed to the Taylor regime, while Kollie had been appointed under the Taylor regime in 1998. Dunbar had been a key figure in obtaining accreditation for SRU and was paid a retainer by SRU to answer the many requests for verification of SRU directed to the embassy as well as additional fees for extra work when required. Kollie, meanwhile, would later be cited as having provided assistance to the US authorities in the SRU prosecutions(3).

Dunbar was responsible for sending official letters to several US-based critics of SRU, defending the university and its accreditation.

>>Dunbar to Oregon Office of Degree Authorization, 10 March 2003

>>Dunbar to Ten Speed Press, 10 March 2003

In June 2003, Dunbar was recalled to Monrovia, but refused to go. He maintained that the recall was void because it was part of a plot by Kollie and others to sack him. When he attended the Liberian peace talks with Novak in Ghana in August 2003, Novak lobbied for Dunbar’s reinstatement. Meanwhile, the US State Department confirmed Dunbar’s recall and withdrew his diplomatic status, with the result that Dunbar returned to Monrovia in October 2003.

During Aaron Kollie’s time in charge of the Embassy, he had refused to confirm the accreditation of SRU to enquirers and issued the following statement in September 2003,

The Embassy of Liberia in Washington, DC wishes to dissociate itself and to announce that it has no official dealings with the online St. Regis University. The Embassy of Liberia is not a source to verify or authenticate the accreditation status of St. Regis University, and would as such assume no responsibility for any reference to the Embassy. Anyone seeking clarification on the status of St. Regis University should channel same directly to St. Regis.

Sgd: Aaron B. Kollie, Charge d’Affaires

After this, Kollie was contacted by SRU, and it became clear that he would be prepared to confirm SRU’s accreditation, so long as SRU arranged to pay him a similar retainer to that which they had paid Dunbar. Kollie was paid a sum of money, but events overtook the arrangement.

Dunbar arrived back in the Washington embassy shortly after his departure, this time bearing two letters from the new administration, one confirming his appointment as Chargé d’Affaires, and the other recalling Kollie. This time, Kollie refused to depart, and the two men ran rival administrations from the same embassy until the matter was finally resolved in Dunbar’s favour in December 2003(4). Dunbar would serve as head of the mission until the appointment of S. Prince Porte as Chargé d’Affaires in February 2004. Porte served until the appointment of Charles A. Minor as Ambassador in June 2004. According to Dunbar, Charles Minor was opposed to him, just as Kollie had been, because of Dunbar’s known antipathy to the Taylor regime.

Because of the confusion Kollie’s statement had brought about, Dr Bestman of the National Commission of Higher Education wrote the following letter to Oregon’s Office of Degree Authorization on 20 October 2003:

On 11 September 2003, the National Commission of Higher Education under Dr Bestman issued a document recognizing and authenticating SRU as a further measure to combat Kollie’s disinformation.

This document was authenticated by the Liberian Ministry of Justice on 2 February 2004:

and by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs the following day:

On 16 October 2003, SRU was awarded accreditation for a further five year period by the National Commission of Higher Education. This took it beyond the two year accreditation period awarded by the Commission on 28 August 2002, which would have expired on 27 August 2004.

The accreditation document and the charter that accompanied it would bring SRU into compliance with the published National Policy requirements. The Charter was very obviously not created in 1984, since it makes reference to delivering programmes via the Internet. However, this document was backdated to the original date of the creation of the Liberian school that subsequently became SRU with the full knowledge and blessing of the National Commission on Higher Education and its Executive Director, Dr Lawrence Bestman. Governments can and do enact retrospective provisions, and may also provide for the legality and validity of backdated documents.

>>SRU Charter

In mid-2003, I spoke to Dr Lawrence Bestman, Executive Director of the National Commission on Higher Education, on the telephone. My purpose in speaking with him was to establish the authenticity of SRU’s accreditation documents and also to gain some impression of the position of the Ministry of Education on distance learning and related matters. Our conversation lasted the best part of an hour, during which he confirmed that SRU was a totally legitimate Liberian university, and stated that he had dealt with them for about five years. Indeed, he had himself graduated from SRU during the 1990s. He confirmed that the National Commission of Higher Education under him was the only entity licensed to accredit universities in Liberia, and informed me that the accreditation process was “rigorous”. He was insistent that I should refer all enquiries to him directly, and that he was the authorized authority of the Ministry of Education to deal with all accreditation matters. He stated emphatically that the charter and the accreditation certificates that bore his signature were authentic.

Ambassador Prince Porte also issued a document on 18 March 2004 disclaiming Kollie’s actions and reaffirming the accreditation of SRU by Dr Bestman on 16 October 2003, including a list of recognized Liberian universities that had been prepared Dr Roland at the Ministry of Education:

I spoke by telephone to Abdulah Dunbar in January 2004, and to the Chargé d’Affaires at the Liberian Embassy in Ghana, Andrew Kronyanh. They both confirmed the accreditation to me and spoke highly of SRU. I spoke on two occasions to the Liberian Embassy in London, UK. On the first occasion, they told me that they had never heard of SRU. I reported this when speaking with Dunbar, who assured me he would deal with the matter. On the second occasion I called the London embassy in May 2004, they confirmed that SRU was on the list of recognized universities in Liberia.

On 27 May 2004, Prince Porte wrote to the newly appointed Liberian Ambassador in Washington, D.C., Charles Minor, confirming the authenticity of SRU and its accreditation as issued by Dr Bestman on 16 October 2003:

5. Trouble for SRU

One aspect of SRU that caused controversy was the anonymity of its advisors, who were referred to either by their first names or by aliases. Dixie explained this by saying,

“Most of the advisors were female, and wanted online anonymity. I came to know Kristiaan De Ley, owner of Concordia College & University, and he recommended the use of online names, and did this also at his university. He found the males were treated differently, and many females were often dismissed as “secretaries” or even harassed. He told me that females faced some discrimination and were not always treated with the same respect as the males. I also noticed many online schools, businesses and universities used only first names or screen names, so it made sense at the time.”

Dixie herself used a number of male aliases, including “Dr Thomas Carper” and “Patrick O’Brien”. At that time, entrepreneurs in postsecondary education were rare and female entrepreneurs vanishingly so.

As SRU got bigger, so it ran into difficulties. According to Dixie,

In the beginning, all advisors were well trained, some with teaching degrees, and others with experience in related fields.

But, as SRU grew and became very successful, many people came to us wanting to be “affiliates.” This was a time that online affiliate programs were quite new, but we had people from countries all over the world who wanted to be a part of this great new enterprise. I spent hours, weeks, months, training these new affiliates, and at first I saw no problems. But, as I am sure you are aware, some had other ideas….bad ones. One advisor, who was actually working on our Spokane office, using my equipment, staff, everything, simply copied my website. Word for word, and connected it all to his email addresses and credit card accounts and began issuing degrees – based on nothing at all.

We discovered this, by accident, got rid of him and shut down his fake sites, but damage was done. Then, some similar things happened with affiliates overseas, and I soon found I was losing control of what these people were doing.

At times I did have to speak to advisors for giving credit for fake submissions, or getting greedy and accepting just money without careful evaluation for equivalency. I believe overall, our staff did an excellent job, but it may be that some sloppy work got through from affiliates and people who just copied and stole our identity.”

Realistically, SRU had now developed into a major international enterprise that could only have been kept under control through building an equally significant administrative network through which authority could be delegated and each aspect of its operations managed closely and effectively. This would also need better systems designed to prevent the assessment processes from being abused. The problems were compounded by the fact that any failure was, of course, eagerly seized upon by the academic establishment and the newspapers.

SRU worded its application and disclaimers very carefully to avoid misleading clients. Dixie recalls,

SRU degrees were granted to politicians, judges, several prison wardens, CEOs, clergy, and people from all walks of life. We knew of no problems at all from any degree holder. When degrees were confirmed the inquirer was simply told the person had a degree and never were they told that anyone attended classes or took courses, or that SRU or other universities were “schools.” Every degree holder knew exactly how they earned their degree and was involved in the process.

In 2003, SRU created an alumni forum, and strong bonds began to develop among the eclectic mix of characters that emerged there, who included some who were now professors at SRU. It was not long before there was a concerted effort by this group to try to address external concerns regarding SRU and to help it achieve its potential. There was also much internal criticism and suggestions for improvement, some of which were acted upon.

There was also a movement to try to supply aid to Liberia to help with regeneration after the civil war, and some US$28,000 was raised for this purpose. Robert Stefaniak, one of SRU’s graduates and professors, who co-ordinated the effort, said this of it,

“Every dollar donated is matched with SRU matching funds. One dollar is then worth two and that becomes $120.00 Liberian.

Where else can you donate say $10.00 to a needed charity and have that ten bucks turn into $20 US and turn into a Liberian total of $1,200.00 worth of aid to people recovering from years of civil war, food shortages, water pollution, and outbreaks of cholera and dysentery? Getting kids back to school with education assistance is a major thrust of our goal as we work with the African Methodist Episcopal University in Monrovia, Liberia through their director Dr. Louise York.

Children in Liberia need to get healthy before they can return to the business of education and focus on rebuilding their lives, now that peacekeepers are in place and a new transitional government restores constitutional law and order under the watchful eye of the UN and the worldwide community.

You may want to give directly through the UN or other NGO non government organizations often faith based. But, your gift through our alumni association drive is automatically doubled with SRU matching all donations.”

SRU’s enemies were quick to try to portray SRU as exploiting Liberia in conditions of war and poverty. However, the reality was not only that Liberia had given SRU strong support from the outset but also that there was a sincere wish among many involved to see Liberia recover and strengthen from the recent conflict. When SRU was represented at Liberia’s peace talks, it was as a valued NGO with contacts at every level of government, seen as a key player in Liberia’s development and in the bid to credential its citizens.

Professorship at SRU was, for most holders, not a remunerated position. The advisors handled the assessment of candidates, and one role of the professors was intended to be to deal with any candidates who did not qualify based on initial assessment, and then needed to complete some form of top-up coursework or dissertation to qualify. Some professors did advise candidates in this way.

For most SRU professors, however, professorship was an honorary title, which could also be obtained by purchase for qualified candidates. Only a minority of professors were listed on the websites, some of whom were highly accomplished individuals. The alumni forum had called for more Liberian professors to be added to the faculty, and as a result a number from the African Methodist Episcopal University were appointed in 2003-04. These were remunerated by SRU, but were unable to do much for it since the poor state of telecommunications networks in Liberia meant that the Internet was often inaccessible for long periods.

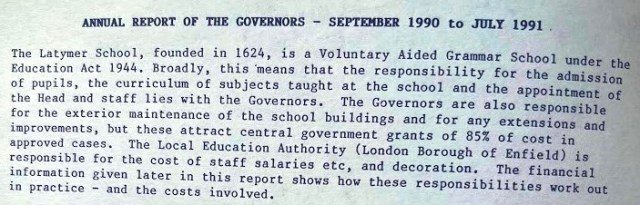

The professors were encouraged subsequently to develop distance learning courses. In October 2004, SRU relaunched with a series of schools – business, marketing, behavioural sciences etc. which were independently-run on a franchise model. This model would transfer to James Monroe University on SRU’s closure. It addressed long-held criticism that SRU did not teach or offer courses.

Some of those involved in course development had also been involved with the University College for Advanced Studies, which had launched in January 2004 from a base in Greece, owned by one of the SRU professors. This prepared students for degrees awarded by SRU and several other universities. In 2005, the majority of this work was transferred to a short-lived new affiliated school incorporated in Panama called Athenaeum University International. This had prepared students for JMU degrees. It closed in 2006.

At an early stage, SRU had come up against opposition from individuals and powerful institutions with a specific agenda. On the surface, that agenda was consumer protection and the combatting of fraud and criminal activity in education. Beneath the surface, what was really going on was specific advocacy against those schools and individuals who threatened the vested interests of the American educational establishment, with SRU perceived as constituting the greatest danger. Too often, the tactics of “diploma mill hunters” have blurred the distinction between diploma mills and legitimate alternative schools, and between those who use degrees with the intent to commit fraud and those who are in fact unwitting victims of that fraud.

Most obviously, the matter is deeply personal for those concerned. The inherent subjectivity of education leads to the situation where one man’s diploma mill is another’s alternative university. Such clashes do not stay dormant for long. They find expression in vendettas, rivalries, trolling and abuse that are all too familiar to readers of internet discussion forums. And at times, this behavior goes offline, sometimes with serious consequences. SRU was never given a fair hearing, with its defenders ridiculed, banned and attacked on and offline from the outset, and this sparked a predictable reaction. In retrospect, by far the best strategy would have been simply to have ignored much of what was being said, and yet those involved on SRU’s side felt, understandably, that there was a strong chance (given the evidence) that they could prevail. In the course of this process, the most vociferous of the anti-SRU internet forums, degreeinfo.com, would unexpectedly be exposed as having close links with epebophile pornography, a preference that has always been suspected to be close to the hidden circles of the deep establishment.

The discussion forums included members of the academic establishment and others whose networks included the gatekeepers of that establishment – college registrars, admissions officers, some foreign credential evaluators, and others involved in activism. A further category was those officials involved in administering laws in certain US states against the use of degrees from domestic and foreign universities that were not considered to have the equivalent of recognized US accreditation. The judgements involved were based on opinion, but were too often presented with the certainty of the zealot.

In July 2003, the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO) issued a statement concerning SRU:

“Saint Regis University” is a virtual university claiming recognition by the Ministry of Education of Liberia. Recently, the Ministry of Education in Liberia has recognized a number of virtual universities, few of which have any actual physical entity in Liberia. Most of these virtual universities use the same address in Monrovia. Recognition of an institution by the appropriate educational authority of a country is usually strong evidence of the credibility of its issued academic awards as comparable to similar awards in the United States. However, as the standards of recognition of institutions in some countries may vary due to local conditions such as civil war and economic hardship, simple recognition by a foreign government alone cannot be considered an automatic guarantee of comparability to a United States academic award and each country’s system must be judged on its own merits in this regard. Therefore, while we acknowledge previous recognition by the Ministry of Education of Liberia of the following universities – the University of Liberia, Cuttington University College, and the African Methodist Episcopal University – we do not accept the recognition of Saint Regis University by the Ministry of Education on Liberia as comparable with the recognition afforded the three above referenced universities and AACRAO considers Saint Regis University to be comparable to an entity in the United States that does not have regional academic accreditation.

AACRAO importantly did not deny that SRU was accredited by the Liberian government; rather, it questioned the meaning of that accreditation and its comparability to US standards. Others concerned with foreign credential evaluation, as has been shown above, did not find those aspects to be problematic.

In mid-2003, Dixie created websites at the domains liberiaembassy.com and liberianembassy.com. She has said of this,

One question that came up almost every day – “Is SRU accredited”? We had a certificate and accreditation was genuine but there was no way to verify it. So, I asked someone in the Department of Education, I think it was Isaac Roland, if they’d post accreditations at their website. I was told they had no website. I asked if they might have one soon, and there was no plan for this. We discussed that there was no way for the public to see the accreditation of any Liberian schools so they needed a website for this and many other uses. I had Rick [Novak] meet with Bestman, Prince Porte and Roland, in Monrovia, to offer to build one for them, as we had a good relationship and they did a lot for us.

So, one of our techs built it but it was put into control of one of their government officials. They not only knew, they wanted us to do this, and seemed to be happy with it.

The websites gave general information about Liberia and a list of recognized universities, including SRU, with a verification email. The contact for the websites at the Liberian Embassy in Washington, DC, was the Consul General, Mrs Stataria Cooper, who answered all telephone enquiries arising from them.

An email address associated with these websites was used by Dixie to send email to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, complaining that Dr George Gollin was using his faculty webpage to publish material attacking SRU. Gollin reported that in August 2003 he had taken the online test for SRU’s high school division twice, scoring 26 and 21 per cent respectively, and being offered an associate’s degree both times. UIUC initially sided with SRU and ordered Gollin to remove the material from his website(5), an act which he has referred to as trying to “drop the University of Illinois on me like an anvil.”(6) Subsequently, after protest, UIUC reversed its decision. But by then, SRU had made a mortal enemy in Gollin, and one who would develop a host of contacts with accreditation agencies, education regulators, the academic establishment, government and assorted diploma mill vigilantes. Gollin had no doubt that he was morally in the right. He said of SRU, “These sons of bitches who smell money are just using the situation [in Liberia] there for their own ends,” says Gollin. “They’re monsters. They’re just disgusting monsters.”(7) Gollin was quoted in a later interview as saying, “My anger about all this just stuck.” So did his thirst for revenge. “I was going to fuck them.”(8)

In October 2003, George Gollin tried unsuccessfully to get the FTC to sue SRU. That winter, he wrote a document entitled “Information about the “National Board of Education”, Saint Regis University and American Coastline University”. This was added to by John Bear, the author of a well-known distance learning guide, who had both operated diploma mills and subsequently acted as a consultant to the FBI in diploma mill prosecutions. Alan Contreras, administrator of Oregon’s Office of Degree Authorization, also became involved in the anti-SRU campaign. Gollin’s document reached Washington’s Attorney-General, but there was no willingness to file suit. In time, all three antagonists would correspond privately with Dixie. She recalls,

I did try to talk to Bear, because I wanted his help to make any corrections he thought were needed to stop all the issues with Gollin. But, he was more interested in being Gollin’s friend…it almost seemed he was envious of SRU.

Unfortunately, the document was inaccurate in some respects. It named Dr Richard J. Hoyer, who had been SRU’s provost on a volunteer basis between February and October 2002, as a major force behind SRU. In fact, Hoyer had discontinued his involvement and stepped down soon after SRU became accredited in Liberia, and was never an owner or manager of SRU. John Bear had other ideas, however. Writing at degreeinfo.com in August 2003, he said, “For the record, Richard Hoyer, who at one time controlled American Coastline University is also a (or the) founder of St. Regis University.”(9) This produced a furious remonstration from Hoyer, which Bear proceeded to ridicule and then ignore. In October 2003, Bear would wrongly attribute the Liberian Embassy website to Hoyer too, stating “Richard Hoyer sets up a a Liberian embassy site, which supports the accreditation of St. Regis University.”(10) In fact, the Liberian Embassy website had absolutely nothing to do with Hoyer. Did the accusers check? Did they care? Not if it suited their agenda. Hoyer would eventually publish his own reply on the forums, entitled “Stalking in the Guise of Academic Freedom”.

SRU graduates began to be targeted, too. Eleven teachers in Georgia with SRU degrees had been awarded pay raises on the basis of their new degrees. What had once been acceptable to the board ceased to be so once activists and journalists started their campaign, and all were banned from working in Georgia public schools.

It was easy for those opposed to SRU to convince the majority that SRU was not legitimate. Most people know little or nothing of higher education methodology beyond the practices of traditional brick-and-mortar schools. The idea of a progressive non-traditional distance-learning establishment that challenges these practices in a controversial way is not what people expect from education, largely because their expectation is rooted in state control and time-serving. The public view of educational standards is largely a detached one, and the idea that those standards might be highly subjective is disconcerting to them. They are readily persuadable that experiential credit is at best “easy” and at worst fraudulent, and that “real” education consists of sitting in a classroom receiving instruction, doing assignments and taking exams. They are unfamiliar with theorists such as Elizabeth Monroe Drews, who wrote “It is immoral for us to squander [the learner’s] time by asking him to learn what he already knows”(11). They are also used to taking national accreditation as a definitive indicator of acceptability. In some countries, practices just as controversial as those of SRU are undertaken at nationally accredited schools, but because those schools do not target the US market, they pass without notice.

Moreover, higher education is highly unionized and operates as a cartel. It could not be less market-friendly if it tried, and that is before we get to the overwhelmingly left-wing bias of academics. Indeed, the unfettered free market is the enemy of mainstream education as currently constituted. SRU met that market directly at its point of need, rather than funneling the market through the narrow and artificial aperture that mainstream academia imposed. The cognitive dissonance this created could only be met with condemnation from those who had something to lose from SRU’s innovation.

SRU had hoped to be included in the authoritative International Association of Universities/UNESCO World Handbook of Universities. Listing of institutions is based on their forwarding by the government ministry responsible, and the following letter was issued on 18 October 2003,

Despite this, the intervention of opponents soon meant that SRU’s inclusion in the Handbook was not to be.

During May 2004, Senator Susan Collins held US Senate hearings on the subject of diploma mills. SRU’s enemies in the US accreditation cartel ensured that it was mentioned unfavourably and given no opportunity for right of reply or a balanced presentation. Bear’s former colleague Allen Ezell, a retired FBI agent, spoke on SRU, and inter alia repeated the false statement that Richard Hoyer operated SRU.

This was the point when, according to Dr Roland, problems with SRU began. In fact, as has been shown, it was well before then that the US education establishment had determined to put SRU out of business in any way possible. Its public denunciation now gave legitimacy and impetus to that mission.

In October 2004, Dr Roland would subsequently write in an email, “At the moment, the U.S. Embassy has and continues to raise serious concerns regarding St Regis. The Embassy has expressed, with grave concern, that the U.S. Government may likely withhold certain financial and technical support for the Ministry of Education.” (Isaac Roland, email to Robert Stefaniak, 6 October 2004) There was a clear trade-off here; if the Liberians continued to support SRU, it would come at the cost of losing much more valuable American foreign aid.

Accordingly, Dr Roland and Chairperson Dr Evelyn S. Kandakai issued a disclaimer of the accreditation of SRU, declaring its documentation null and void.

Dr Roland now further asserted that Dr Lawrence Bestman, who had issued the five-year accreditation certificate to SRU, had been dismissed from his position on 14 October 2003. This was not credible; Dr Bestman was in touch with SRU in his official capacity well after that date, and moreover he was referenced by Justice Kabineh Ja’neh and by Abdulah Dunbar in their communications. The documents he had issued after 14 October 2003 had been authenticated in Liberia and given credence by Liberian government sources, an unlikely position if he had not had the authority to issue them.

The disclaimer was dated 22 July 2004, but it was not published to the web or publicized until October 2004. It was posted at degreeinfo.com on 5 October. Given its supposedly “urgent” status, the delay of several months was curious. It might be speculated that the document was most likely backdated, and that its creation was prompted by pressure from the US government in the wake of the Senate hearings.

All was not lost for SRU. Dr Roland subsequently showed that he was trying to square the circle of standing by the 22 July statement while reconciling it with a more honest account of what had really happened regarding the accreditation. Consider this email from Dr Roland from 3 January 2005, for example:

Because St Regis University, James Monroe University and Robertstown University first applied for accreditation prior to [14 October 2003] it is certain that the school’s officials had no knowledge that their accreditation certificates signed after Bestman was dismissed were not effective. This does not mean that the schools did not meet the criteria to be accredited, and in fact it appears that they each do operate in compliance with all Liberian laws and regulations.

SRU enlisted Prince Porte to intercede on its behalf as well as Novak and Robert Stefaniak, and there was an exchange of emails with Dr Roland leading eventually to his issuing a disclaimer of the disclaimer on 20 December 2004, the text of which had been worked-out with SRU beforehand:

This now meant that SRU was “recognized” but not “accredited” by Liberia – a distinction that had not previously existed. However, it was a distinction largely without significance. No schools in Liberia were now “accredited” since none had yet completed the new process. “Recognized” schools were still fully authorized by the Liberian government to award degrees. The verification of the recognition was still available from Liberian embassies.

Dr Roland’s position was established through interview, recorded in a defence memorandum in the SRU case,

“Dr. Roland stated that because the St. Regis people had been mislead by the previous MoE administration during the Charles Taylor regime, they were not aware that two signatures were required on the accreditation documents and based on the documents they had obtained from the Liberian government should have reasonably believed they were accredited by the Liberian government.

Dr. Roland went on to state that after the disclaimer signed by he and Evelyn Kandakai as posted on the Embassy web site the St. Regis people tried to resolve the situation by interacting with him and Ambassador Prince Porte. Dr. Roland did state that he visited the offices of St. Regis University in Monrovia along with Porte to establish the schools presence in Liberia. After reviewing documents and establishing the presence he subsequently prepared the letter dated December 20, 2004. Roland stated that there was no specific documented process established by the MOE for online schools during the time St. Regis was going through this process, and to this day there is no defined policy or process for the accreditation of online universities.

Dr. Roland stated that his position is that there is a difference between Accreditation and Recognition and although St. Regis was “Recognized” they were not fully accredited, so the list of “Recognized Higher Education Institutions of Liberia” which was- posted on the Embassy web site, which he prepared and signed, was accurate.”

>>Affidavit of Brian R. Breen, filed 7 December 2007

The view taken by Dr Roland in his private correspondence with SRU was that SRU urgently needed to address the concerns about its operations that had been raised in the USA. But once this was done, he foresaw bright prospects. In an email to Stefaniak of 6 October 2004, Dr Roland said, “I have seen the St. Regis catalogue, and the programs and professors are excellent and fantastic; hence, I do not doubt the credibility of the institution.” Dr Roland knew of what he was speaking; he too was a graduate of SRU.

There were also efforts made by Ambassador Prince Porte on his return to Liberia. According to the defence report of interview with Porte, after the disclaimer had been published, “Richard Novak seeking assistance contacted Porte, and Porte agreed to assist Novak through the process of accreditation, including setting up an office for St. Regis University in Monrovia [which was one of the conditions of the accreditation process]. Ambassador Porte did make arrangements for various items of office furniture and computers for the office, which were paid for by Novak via wire transfer. He also made arrangements for staff and once the office was set up went with Dr. Roland to inspect the office. Ambassador Porte stated that once Dr. Roland saw the office he stated that it was better then all of the other ones he had inspected.”

Porte confirmed the views expressed by Dr Roland earlier in response to interview, “Ambassador Porte specifically stated to me that based on the documents provided to St. Regis University prior to the disclaimer from the Ministry of Education, the people associated with St. Regis would have reasonably believed that the University was in fact accredited and recognized by the Liberian Government, and that even after the disclaimer based on Dr. Roland’s list of “Recognized Higher Education Institutions of Liberia”, that they were at the least “Recognized”.’