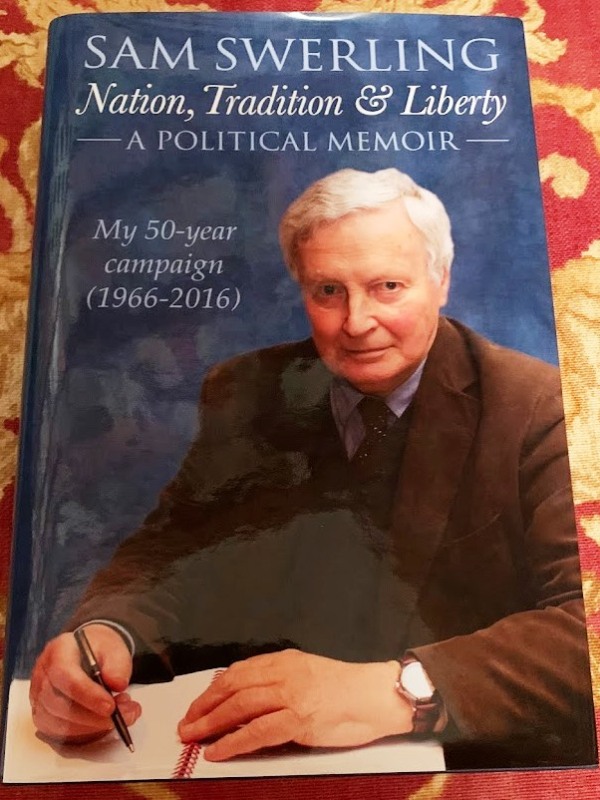

A functioning aristocracy is fundamental to a traditionalist society, and its structures and concepts have greatly influenced the development of British society over the centuries. In this essay, I intend, while showing some of the difficulties that have come to occupy the British aristocracy today, to consider whether the aristocracy as a class may be useful to our nation in firstly seeking to challenge the prevailing structures of the state and secondly offering us a model and structure for a projected traditionalist replacement of it.

Why secessionism?

This essay is written from a secessionist perspective. It addresses both partial secessionist or regionalist solutions, and also explores a limited number of total secessionist solutions. In doing so, it is concerned with secessionism on the basis of geographical regions that form a part of Great Britain, and is not concerned with secession that is not based upon the ownership of land and that therefore applies solely to a non-geographically constituted individual (sovereign individualism) or group.

This paper adopts a secessionist perspective because it recognizes the following conditions to apply:

1. that the government and institutions of Britain have effectively been captured by an enemy political class that, regardless of party affiliation, is dominated by Left-wing ideology and permanently subject to the European Union, as well as supporting a form of global oligarchy that runs counter both to British national interests and to a genuinely free approach to trade;

2. that there is active support from the political class for the destruction of the historic culture, precepts and way of life of the British people, together with the absorption of the British nation into an European super-state, and that it is a fundamental right that the British identity should be able to be preserved against such threats;

3. that there is and has been ineffective control over the borders of the British Isles, such that mass immigration both from within and outside the European Union has been politically sanctioned, as has been admitted, as a means of attack upon the traditional values of Britain;

4. that there is, for the present, little prospect of sufficient mass support against the political class being mobilized through democratic structures, and even were such support to be forthcoming, any political solution would depend to a large extent upon the co-operation of political class itself and its substantial client state;

5. that despite the absence of mass support, there remains a substantial minority of traditionalist conservatives, paleolibertarians and others who are effectively disenfranchised by the political class and who seek alternatives to the prevailing status quo and direction of political so-called “progress”;

6. that this substantial minority is already concentrated geographically in particular areas and regions, such that those regions or subdivisions thereof could potentially produce majority support and therefore consent for a partial or fully secessionist solution;

7. that even if these minority areas were to be small and their secession only partial, nevertheless the gains in returning to a small or human-scale organization of society as distinct from centralized governance from London or Brussels would outweigh the disadvantages of such independence;

8. that such a secessionist solution would offer a peaceful answer to the ideological and cultural division that has come to affect our nation, and would therefore be preferable to any solution that would involve violent conflict or indeed civil war. It would end the current position whereby traditional conservatives are subjugated and disenfranchised by means of the exercise of force by the state, and at the same time seek separation from, rather than the subjugation of, opponents of a broadly traditional way of life, who would be free to continue to administer those areas and regions where their followers were most concentrated;

9. that the proposed solution would be complimentary to existing long-term cultural strategies that aim towards the support of British national heritage and institutions through the creation of an active counter-establishment, ensuring that any secessionist entity could in time grow beyond its initial boundaries;

10. that the proposed solution would look to essentially British and traditionalist entities, in particular the aristocracy and feudal structures, and would thus promote an indigenous settlement of the problems facing us rather than seeking the adoption of any form of modern ideology or historical model that was either so far removed from our era as to be incompatible with it or that was based on a foreign or artificial construct.

Aristocracy – its landed origins and Parliamentary downfall

The origin of the aristocracy is inescapably feudal. The titles of our most venerable nobles are rooted in the land. The Dukes of Norfolk, the Dukes of Somerset, the Dukes of Devonshire, the Earls of Derby, the Barons Hastings; all speak of the feudal past of our country, and of a time when to be an aristocrat was inextricably linked with the ownership and management of territory. The greatest of these landowners sat at the top of a pyramid of feudalism that extended down to the lesser feudal overlords – in England and Wales, the lords of the manor, and in Scotland, the barons and lairds.

The major change that has come to influence this situation has been the gradual alienation of land-ownership from the concept of aristocracy, and the absorption of the aristocracy into a political class. Lords of the land became Lords of Parliament; as the barons were summoned to parliament, so that summons became in time the distinction between peer and commoner. This change was wide-reaching, and ultimately, as I shall show, would prove destructive. The old system was based upon a direct link between the sovereign and the landed aristocracy. The new system interposed a layer of parliamentarians between the two. Initially, the parliamentarians were, of course, themselves landed aristocrats, but that was not to remain the case, and the twin developments of constitutional monarchy and universal enfranchisement served further to weaken the traditional role of the aristocracy. In time, the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 would serve to subjugate the House of Lords entirely to the House of Commons, a reversal of the natural order that has assisted in the decline of our nation.

This is not to say that there have not remained to this day aristocrats who are great landowners. Particularly, but not entirely, in Scotland, this link has remained extremely robust. However, the move towards the parliamentary concept of an aristocrat caused an anomalous situation to arise, whereby a man could be a great landowner, indeed a feudal lord, yet not be a peer on account of the lack of a summons to Parliament. This gave rise to the class which from the sixteenth-century onwards was termed the landed gentry; a class of landowners that includes several notable families who had either never been peers, or whose peerages had become abeyant or had been attainted due to political factors – the family of Scrope of Danby being perhaps the most notable example of these latter conditions.

The loss of the feudal basis for the aristocracy was the beginning of their slow decline. It signified a loss of power, and moreover a loss of that measure of individual sovereignty that the landed aristocrat exercised as an immediate vassal of the king. Administration, which under the feudal system had included the administration of justice, became monopolized through a centralized structure, and the traces of feudalism were in time relegated to the exercise of mineral and fishing rights over particular land and the occasional quaint custom, such as the right of the Lord of the Manor of Worksop to place a glove on the monarch’s right hand at his or her coronation. Appointments to peerages became a matter of political favour and were before long entirely independent of the ownership of land. With the coming of constitutional monarchy, this process accelerated to produce the ancestor of the modern “honours system”; one in which the sovereign was eventually relegated to a mere rubber stamp for appointments made entirely by, and for the benefit of, the political class and its attendant establishment.

Nation and state, and the values of the aristocracy

It is perhaps useful at this point to draw a distinction between the terms nation and state as they are to be used in this essay. The state is that body of administration formed by the political class and its extensions. Those extensions constitute the following entities: large corporations, which cannot flourish without the active support of the state; the supportive administrative apparatus, both local and national, that implements the decisions of the political class; the legislature; the military and the police; the state’s church, and the major institutions that are dependent upon the state for direct or indirect patronage, such as our education system and the majority of the arts establishment. These, then, are the clients of the state; their relationship with the political class is symbiotic and effectively unbreakable. And moreover, the state, for the past few decades and for the foreseeable future, is the creature of the philosophies and ideologies of the Left, both indigenously and as expressed through the European Union.

The nation is not the same as the state. It is a much looser term, defined by a common culture, the origins of its people, their customs, character and manners, and to a large extent influenced by the very land itself and its variety. The feudal system, and the feudal aristocracy, are part of the nation far more than they are part of the state. The nation is less easily defined in purely tangible terms; rather, it is almost a matter of instinct. We might say that we know it when we see it. The nation represents a true and authentic expression of traditionalism and conservatism. It is free from ideology, immune from fashion, a greater entity than those men and women who serve it. Even though we can trace specific events in its history and even pinpoint some of its origins precisely, it feels as if it is independent of the constraints of time; it is our ancestral memory expressed through a living experience.

It is from these broad values as a nation that those specific values develop which we most readily associate with the patrician archetypes of the aristocracy and with noblesse oblige; an ability to take the long view, an independence of mind, a deep sense of rootedness to place and people, and following from this latter a duty to those for whom the aristocrat has responsibility, be they family, tenants, his peers or indeed the nation itself. That is not to imply that all aristocrats are paragons of virtue; far from it. Within aristocracy as a class, nevertheless, there is an expectation of virtue, a code, if you will, that if disappointed causes us to regard the exception to the rule as aberrant; both aristocrat and non-aristocrat understand the high standard that is expected of those who enjoy privilege as of right of birth. In turn, the sensible aristocrat will also realise that his own interests and those of his family depend upon his choices and behaviour, and that excess and greed will result in detriment, whether immediate or delayed until the next generation. The aristocracy did not survive for centuries simply because wealth and position propped it up; its survival was dependent upon the consent of the nation as a whole, which would hardly have supported it had it been seen as merely a narrow self-interest group for the rich. It is because the aristocracy lived out its code that it established such a basis of consent. That code can still be of service to us today.

The sovereign, to a certain extent, is also carefully positioned to epitomize the nation and not the state. Yet here this is a false distinction, for while the sovereign has in theory an independence from the state, in practice the sovereign is bound to agree with the state lest a constitutional crisis be provoked and the supposed will of the people be countermanded. Can it truly be said that a sovereign who has consented – without an apparent murmur – to such heinous wrongs as the absorption of Britain within the European Union, and thus to the effective extinction of our national independence, is not effectively indivisible from the state?

The hereditary principle

Fundamental to our understanding of the true principles of aristocracy, and indeed of the nation of which it is a part, is the hereditary principle. Aristocracy represents, at its origins, the logical means by which land is preserved intact from generation to generation. It is the enshrining of what Roger Scruton has cogently described as the rights of the dead. The fundamental concept in effect here is that what one owns should be conveyed intact not so much to an individual member of one’s family, but to the family itself as represented by its most senior individual. The family name – perhaps seen most clearly in the Scottish clan system – is seen as the primary quality to be preserved in inheritance. The aim is to avoid a situation where, as a result of marriage, the estate passes out of the family and one’s kinsmen by name are thus dispossessed, perhaps losing their lands to another rival clan that will treat them as aliens and give their positions and tenures to their own kinsfolk. It is more desirable, therefore, that the estate be held by a male member of the family than a female, because this is the only way by which the family name may be continually allied with the estate in question. Inheritance by successive males in order of seniority is thus the main system by which both land and peerages have come to be organized. It is through this system that permanence is assured as best it can be; when implemented it means that stability should be the defining characteristic of our land rather than the uncertainties of political whim and opportunism.

In recent years there have been attacks on descent by primogeniture in the case of peerages of the United Kingdom, notably in the case of the Earl Kitchener, whose title became extinct even though there were female descendants of the second Earl living[i]. Legislation has also been introduced to establish “gender equality” in the case of succession to the Crown[ii]. Of course, where land is not in question and the peerage is simply “an award of the state”, one may ask to what extent it matters; the Crown is no longer seen as truly dynastic per se – else, by strict Legitimism, our monarch would be a Jacobite heir – and indeed there was no established surname for the Royal Family at all during the Hanoverian years. Nonetheless, there is in peerage primogeniture more than a vestige of the importance of ancestral name, of descent, of blood – all of which are fundamental components of identity not merely for individual peers, but for the peerage as a class. There are ways around these problems – the Dukes of Northumberland, after all, would but for an eighteenth-century Act of Parliament be Smithsons and not Percys, for their Percy descent is through the female line – and many of the oldest English baronies may descend either to male or to female heirs. But nevertheless, it is primogeniture that is a part of our national warp and weft. It is not a perfect system, yet it still serves to maintain land, family and title as a single unit more than would any other.

The state and aristocracy in opposition

It is the intervention of the state that has caused the acceleration of the slow decline of the aristocracy. That is not to say that the feudal system would not, of itself, have changed and evolved over the centuries. It would be imaginable, though, for Britain to have developed more along the lines of pre-unification Germany had our peers not instead have been absorbed into the political class as Lords of Parliament, with regional autonomy much more a feature of our land. And moreover, as my colleague Sean Gabb has written recently[iii] it is possible to imagine a Britain where the Industrial Revolution happened differently. Without the massive intervention of the state, global corporatism would not have taken hold in the way that it did. Certainly, there would be some centralized production, some international specialization, but this would be taking place within a framework that was still essentially and historically indigenous to the British nation and not simply as an alien extension of the political class.

The relationship between aristocrats and their serfs and franklins would certainly have developed differently in these circumstances. It would more than likely take the form that today’s landed estates have adopted, where the bonds of co-operative endeavour establish common interests between individuals, whatever their class differences, and the permanence and stability offered, not to mention the charity often shown to aged and infirm workers, stands in stark contrast to the mercantile alternatives, with their care for workers defined strictly by the boundaries of contract and legal obligation, and those of pensionable age offloaded to the responsibility of the state. A landed aristocracy would have had more to concern itself than simply profit and competition for their own sake, not least because the majority of the supply for its products would be local and domestic rather than national, thus reducing the number of its likely competitors, but also because the long-term and inter-generational nature of aristocratic interests contrasts starkly with the short-termism of elected politicians concerned with five-year leases upon office.

Of course, we can look to the French Revolution as a major watershed in the spillover of anti-aristocratic sentiments, and the consequent adoption by the Left (notably under the influence of Marx) of class war as a major means of discourse, still very present in the Labour Party of today. The futility of the First World War deprived the officer class of many of its brightest and best. The introduction of punishing death duties robbed many estates of their natural heirs. Legislative change separated both English lordships of the manor and Scottish baronies from the ownership of the lands that went with them historically; they can now be bought and sold simply as titles.

The last days of the aristocracy

What is crucial, however, is this: an aristocracy is an exclusive club, certainly, but it can never be a closed club. There must always be a route in, if an aristocracy is to live. Yet if it was the Left that sought the disestablishment of what was left of the aristocracy, it was as much the Conservative Party that cut them off at the knees. By closing the door to the creation of hereditary peerages, the state has killed our aristocracy through an infinitely slow and tortuous asphyxiation. Every time Debrett’s and Burke’s Peerages are published they list those peerages that have become extinct since the previous issue for want of heirs, or, in the case of life peerages, simply through the death of the holder. The list grows ever longer. Just as some peerages are well supplied with heirs, others hang by a thread. The Dukedom of Westminster has only one heir at present; if he should die without male issue, the dukedom will die with him. We have already lost the Dukes of Leeds, Portland and Newcastle within the past century. And it is doubtful as to whether life peers, for all their profusion, are aristocrats in any true sense of that word.

Just as long ago, the peerage had exchanged a position in the nation as territorial administrators for one as parliamentary governors; now in turn the logical conclusion of that process is working itself out: the hereditary peers are gradually being lost from even that role and it seems that the majority of life peers view their role as akin to members of an appointed senate rather than being in any sense part of the nation’s permanent settlement. This, then, is the beginning of the end; those peers who are great landowners will doubtless be able to withstand even this change, but those who are not will increasingly need to look for a redefinition of their role within a country that has decided that they are surplus to requirements.

Peers stand up to Parliament

This is not to imply that there are not within our peerage today those who have a very sound view indeed of their obligations to our nation and a willingness to act upon that duty. In 2001, four hereditary peers, acting under the settlement of Magna Carta, clause 61, and with the pledge of support of many more, presented a petition to the Queen to urge her to block provisions of the Treaty of Nice which they rightly pointed out would destroy fundamental provisions of British liberties[iv]. The clause in question provided that if the Sovereign did not observe Magna Carta, the people would be justified in waging war upon her, seizing lands, castles and possessions until they obtained redress. A period of forty days was given for the Sovereign’s response, but response came there none.

As will be obvious, there has been no outbreak of civil war and certainly no recorded response from the peers in question, but this position serves amply to reinforce my earlier comments about the sovereign as part of the state, and only symbolically part of the nation. A number of individuals have entered into a common law state of Lawful Rebellion as a result of these events, in which they have served petitions upon the Queen declaring that their allegiance is now to the Barons’ Committee rather than to Parliament, and that they are therefore exempt from various forms of taxation and state charges[v]. In doing so, they have not gained the endorsement of that committee or any individual member of it, but have instead relied upon the same provisions of Magna Carta as formed the basis of the 2001 petition.

We may at least derive some degree of comfort from the fact that the intricacy of the legal arguments that surround Lawful Rebellion can be used by its adherents to impose delay and confusion upon what is already a strained and inefficient system, but the eventual results of these endeavours, should they embrace any form of widespread popular movement, will surely ultimately be the same as any others that seek to oppose the state; since the state has a monopoly on force, it will use that force against any threat to its position regardless of any moral, historical or legal legitimacy that might otherwise prove an impediment. We should not forget that the power of the state is based entirely upon force; those who resist, and keep on resisting, will be imprisoned, and those who resist imprisonment will be killed.

The prospects for the aristocracy

We must be clear, then, that our aristocracy is today in an extremely difficult position. It is largely excluded, and will before long be entirely excluded, from its legislative role. It has lost much of the territorial role that it once had. The feudal system that once gave it vitality has been dismantled. Year by year, hereditary peerages become extinct and no more are created. The state promotes an egalitarian ideology in which aristocracy is less important than mere celebrity, and pays court to an elite of wealthy globalists who show little regard for the historic British ways of life. The outlook does not appear promising.

Before we discuss solutions, let us point out one additional factor. This is that the opposition to any aristocratic counter-establishment is likely to come from at least some of our existing aristocrats. State patronage and position is a heady brew, and it is not easy to wean people off it. There are still many conservatives who have not grasped that a loyalty to the institutions of the political class is a loyalty to style and not to substance. They remain within, and supportive of, the current establishment even though that establishment has – across all parties – actively supported their disenfranchisement and eventual extinction. Perhaps some hope that things will, in the end, turn around and that if only the right people are in the right positions some progress may be made. I do not share that optimism, and indeed at this stage it would appear to be the last gasp of a drowning man.

How can the aristocracy be saved to useful purpose?

Now, let us examine how the drowning man may yet be saved. In the first place, we should be clear that we are advocating the preservation of aristocracy as a defined class, with its accompanying context and structures, and not simply endorsing individual peers, however worthy they may be. We can then establish the following steps:

– The preservation of aristocracy and the re-establishment of aristocratic structures as a partial or complete alternative to the state as I have defined it, and as a means of solving the current difficulties that have arisen through power passing into the hands of a centralized political class;

– The need for aristocracy to continue to represent an exclusive and defined class, but also an open class, ie. that there are circumstances where someone who is not at present an aristocrat can become one. If we do not do this, the aristocracy will face etiolation and eventual extinction, and it will also risk becoming a monopolist body;

– We are not proposing a return to a medieval feudalism or to serfdom, but rather that feudal principles can be re-interpreted with regard to our own age, on similar lines to the management and organization of many of the major landed estates today;

– We are concerned with this preservation firstly because it will re-establish a future for our country that is based upon long-term interests and sound, sustainable principles, and secondly because it returns our country to its natural, historic and time-honoured order and rejects the egalitarian ideology that has done it such harm;

– In our process of preservation and re-establishment, we must accept that the aristocracy of our projected future will not be the same as that of its parliamentary past. We must be prepared to be radical traditionalists.

A future society that seeks to establish traditionalist principles must be based initially on a strict interpretation of propertarianism, as set out by Murray Rothbard (“Ethics of Liberty”) and Hans-Hermann Hoppe (“Economics and Ethics of Private Property”). A private property society establishes a means of social organization that does not depend upon a political state. Indeed, it is above politics altogether. Individuals, families and in some cases covenanting communities own land and determine the use of that land, including who will live and work on it, who will exercise rights over it, and under what conditions those grants will be made. The state ceases to be a surrogate for its people in exercising land ownership or establishing a monopoly on its use. It ceases to exercise a role in centralized taxation.

The role of feudal structures in a revived propertarian aristocracy

If we seek an indigenous solution to the issues of property, the basic land unit of this future society would most naturally be the manor. Manors, being a feudal structure, are among the oldest dignities in England and Wales that are still extant, and all date to before the statute Quia emptores of 1290. Ownership of a manor within a propertarian neo-feudal structure is likely to engage the owner in a range of responsibilities, relating to commerce and trade, the local administration of justice through courts leet (in accordance with a specific bill of rights or code of private law), the maintenance of or contribution to a militia, the payment and housing of employees, and provision (typically organised through the voluntary sector) of healthcare, education and welfare facilities for the sick and elderly. There would also be significant responsibilities for the spiritual welfare of the manor, through the responsibility of the lord of the manor to appoint the parish priest or other clergy, as well as to establish provision for religious worship of those kinds that are held to be desirable. There would further be responsibilities for border control and relationships with neighbouring communities, enabling co-operative alliances and ensuring that areas where centralization was considered essential could be conducted through shared facilities and access agreements.

It should not be thought that this is anything terribly unusual. Several of the Crown Dependencies have implemented something that – at least until quite recently, and perhaps even still – is not dissimilar to just such a plan. Life in the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey is not by any definition medieval, and yet these places are far closer to the model of propertarian feudal governance that I have proposed than they are to the state control of mainland Britain. Indeed, until external pressure was applied in 2008, Sark was governed via a wholly feudal system, with the Seigneur ruling it as a fiefdom of the Crown. All of these places have a provision for representation of the people, and in most cases this consists of a formal parliament. That parliament has distinct differences from the mainland state structures, however. On Sark prior to 2008, for example, representation was confined to those who were landed tenants. Likewise, the powers of representation in such small bodies can be limited in ways that seek to concentrate upon areas of common interest rather than any infringement upon the rights of individual landowners.

There will be some who may say that this is all too agrarian, that it makes no allowance for industry or for large-scale business. We should be realistic in that almost all of Britain’s heavy industry has now been lost and that it is not likely to return. Certainly, there are foreign businesses that choose to bring their industrial requirements to Britain. But the system I propose can accommodate this. When we speak of a manor, that entity can as easily be formed of industrial plant or a major shopping centre as farmland. None of this alters the fact that a propertarian system can encompass any type of commercial activity. It simply alters the means by which the land upon which that activity takes place is governed, and results in the landowner having the effective power and responsibility concerning the use of that land without being disenfranchised by the state.

Is secession as a Crown Dependency possible?

If an area of mainland England were to find the proposed form of organization attractive and to decide that it wished to take advantage of it, it could perhaps seek to remove itself from the United Kingdom and to redesignate itself as a Crown Dependency. There is no apparent minimum size limit on a Crown Dependency – some of the Channel Islands are very small in population as well as in geographical area. A single manor or group of manors could in theory constitute a Crown Dependency. A Crown Dependency also has a different relationship with the European Union from that which applies to the United Kingdom. The existing Dependencies have chosen to permit the free movement of goods but not the free movement of people, services or capital. They are exempt from the Common Agricultural Policy and in the case of the Channel Islands, from VAT.

But we should not imagine that this would be an easy process. The first challenge would be to secure effective ownership of the land in question. Purchasing the relevant Lordship of the Manor is not enough to do this. The Feudal Tenures Act 1660 abolished feudal tenure. Today, manorial lordships can be separated from their lands, and the last of the effective structures of the manor in the form of copyhold tenancies were abolished in 1925. The right to manorial incidents – that is to say, rights held by a lord of the manor over other people’s land – lapsed in October 2013 unless those rights had by then been registered with the Land Registry. As a result, we must look to freehold ownership to establish the necessary basis for action. Supposing that this were done – after all, it is not unknown for substantial landed estates and interests to be held in private hands in Britain – and a petition for Crown Dependency status submitted to the Queen? What next?

We have already established that the Queen made no response to the petition by the Barons in 2001. In 2008, Stuart Hill, who had purchased the Scottish island of Forewick Holm, maintained that the island and indeed the entirety of Shetland were illegally incorporated into Great Britain in the Act of Union of 1707, and presented a Declaration of Direct Dependence to the Queen seeking to establish what he has designated as Forvik as a Crown Dependency under his Stewardship[vi]. The Queen has not made any response to this document, but the Department of Justice – in other words the state – issued a statement the day before Hill’s declaration was published saying that Forvik is an integral part of the UK. Hill has since declared full independence for Forvik in view of the lack of any response from the Queen to his declaration. Because Hill is seeking to contest this point in law, and believes that he is in the right with regard to the relevant historical and legal arguments, he welcomes any resulting conflict with the UK government. However, in the only court case so far to hear any of Hill’s arguments, they were simply rejected out of hand without any investigation of their merits; the court assumed jurisdiction and proceeded to jail Hill for traffic offences relating to driving what he has designated as a Forvik consular vehicle on the Scottish mainland. This again establishes the principle that the state will not engage with arguments about its authority, since its authority is primarily established and exercised by means of force.

It seems highly probable that were another attempt made to convert part of the United Kingdom to Crown Dependency status, particularly if that part were relatively small and sparsely populated, it would meet with non-response from the Queen and hostile action towards those involved from the authorities. There would appear to be a case for regarding the Queen not as superior to the constitutional settlement but in fact something closely approaching a prisoner of it, in that she can take no action of governance that is not specifically countenanced under that settlement – and is thus effectively subject to the state, even when the interests of the state run directly counter to her own views as to what may be in the best interests of the nation. The state will not give up any of its territory without a fight, and it is uninterested in the Queensberry Rules. Only if the territory were substantial and fairly heavily populated would it become an option that would stand a chance of success; even in the case of Scotland itself, which is large, populous and has elected a nationalist government, the road to independence appears to be far from smooth.

Can the Barons’ Committee offer an alternative?

If the concept of a Crown Dependency is not available, we might instead look to place our territory under the authority of the Barons’ Committee acting as a surrogate for the Crown, and effectively holding that we had entered Lawful Rebellion. But to do so would by now to have entered into open conflict with the powers that be, and it would rely on the robustness of the Barons’ Committee to step up to the role that was now expected of it. The Barons’ Committee would need to engage in an active opposition to the British government, providing an alternative (and more legitimate) source of governance and guardianship of the nation’s conscience. It would need to be able to govern those who wished to place themselves under its authority efficiently, with widespread consent, and without the ensuing crisis of power provoking open conflict with those loyal to Parliament. A central question would inevitably be whether the Barons’ Committee was up to the job. Are our present generation of aristocrats the heirs to the spirit of their ancestors, or simply the parasitic beneficiaries of generations of political patronage? It may well be that such a challenge would produce interesting results.

Some indication of likely outcome might be gained from the approach of the Barons’ Committee to their petition to the Crown. A brief survey of press coverage of the matter shows that this is sparse. None of the members of the Committee appear to have given an interview to the press on the outcome of the matter, or considered its implications given their earlier stance. No website or published journal represents their interests. Significantly, none of the members of the Committee have, apparently, exercised their claimed rights under Magna Carta, entered Lawful Rebellion, or advised others to act in furtherance of these rights. We must ask: was their rebellion merely a publicity stunt or empty gesture? It seems too serious a matter – and they too serious a body of people – to be subject to such a response. If the Barons’ Committee meant what it said then, it would have to either follow through on those principles or openly recant them. Perhaps we shall yet hear from them as to their plan of action and proposals for our country’s future. Until we do, any allegiance that is pledged to them would appear to rest on insecure foundations.

In a strange way, any bisection of Britain caused by the Barons’ Committee forming an alternative government would re-open precisely the same sorts of historic questions that were at issue in the English Civil War, in which Crown was set against Parliament, except that in this case, the very position of the monarch would be one of the issues to be decided – could the Queen be liberated from her position as a “prisoner of the constitution” and reinstated as the head of an aristocratic feudal structure? Or, indeed, as might well be agreed to be preferable, could she in fact combine both roles? Just as Sean Gabb imagined a position in which the Industrial Revolution had happened differently, can we perhaps imagine a position in which the culmination of the strife of the 1640s was not regicide and the Puritan dictatorship, to be followed by the compromised Restoration of 1660, but instead a voluntary separation between Royalists and Puritans, with each determining to live within their own communities and to allow their opponents their differences?

Concluding thoughts

Such a suggestion raises again the issues that we set out at the beginning of this essay, and specifically whether secession can be achieved peacefully and without rancour by those who wish for a non-violent means of living in the manner that they choose. Logic and libertarian theory says that this must be possible. History is less favourable, pointing to the tendency for the assertion of human difference to result, sooner or later, in armed conflict and bloodshed between different groups. Yet this is where, perhaps, we can learn history’s lessons and determine that such an end is not inevitable. It is, indeed, the forcing of human difference into an artificial and often oppressive state hegemony that is the most likely means of bringing about unpredictable and destructive revolt. Alternatives to that hegemony, be they cultural, territorial or, indeed, secessionist, are a means of releasing pressures that would otherwise be overwhelming; they are ultimately the expression of the self-determination that lies at the heart of any humane vision of mankind.

It seems clear that Crown and Parliament will not be separated, at least in their present state. The Queen has shown herself unwilling or unable to act independently of Parliament; all attempts to appeal to her directly have been met by a wall of silence and by the action of the state. It is not impossible that a future settlement may change this. Equally, it would be wrong if we did not, given the facts, judge that the Queen, having so comprehensively supported her government throughout, did not bear the joint responsibility with that government for its actions in abdicating our national sovereignty and other rights. We can conclude that the apparent distinction between Crown and Parliament is more illusory than its public image would have it seem.

The revival of aristocratic structures in a neo-feudal propertarian society is not entirely a retrograde step, nor should it be seen as a panacea for all of our present malaises. It would, nevertheless, offer a way forward that is so deeply rooted in the British culture and people that it would probably preserve much that would otherwise be lost and restore a good deal that had already been consigned to history. It seems that such an appeal to aristocracy cannot rely entirely upon the present aristocratic class, for this is composed of those who are the beneficiaries of the patronage of the current system, but should instead look to a renewal of the aristocratic feudal impulse within the modern age and in the light of propertarian theory, knowing that such principles would likely bring about a society that was traditionally structured, stable and sustainable.

[i] “Julian Fellowes: inheritance laws denying my wife a title are outrageous”, Anita Singh, The Telegraph, 13 September 2011: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/picturegalleries/celebritynews/8757793/Julian-Fellowes-inheritance-laws-denying-my-wife-a-title-are-outrageous.html

[ii] Succession to the Crown Act 2013.

[iii] Sean Gabb, Traditionalism and Free Trade: An exercise in libertarian outreach, Libertarian Alliance Blog, 3 November 2013: http://libertarianalliance.wordpress.com/2013/11/03/traditionalism-and-free-trade-an-exercise-in-libertarian-outreach/

[iv] “Peers petition Queen on Europe”, Caroline Davies, The Telegraph, 24 March 2001: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1327734/Peers-petition-Queen-on-Europe.html

[v] See, for example, http://www.lawfulrebellion.org/

[vi] See http://www.forvik.com/ which is Hill’s website setting out his claims.