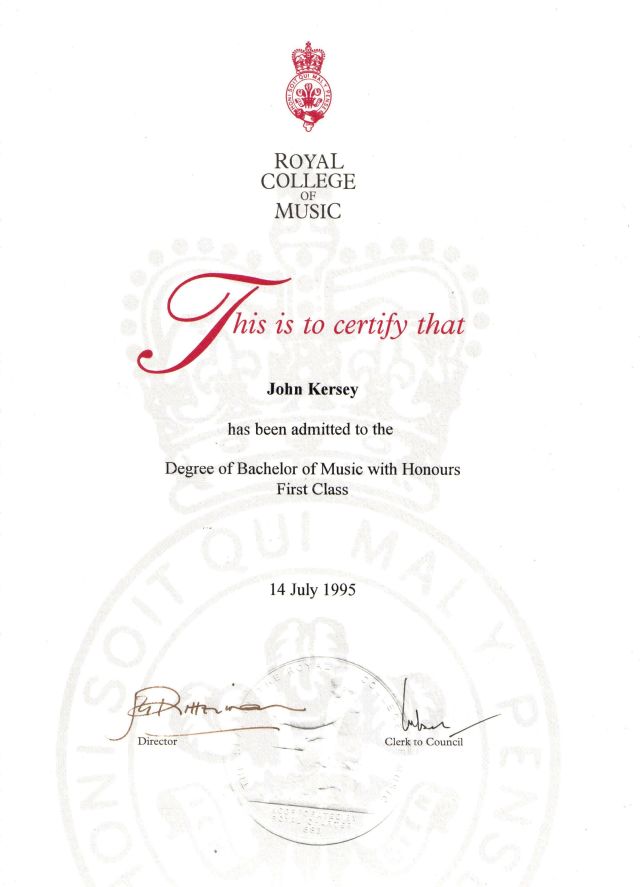

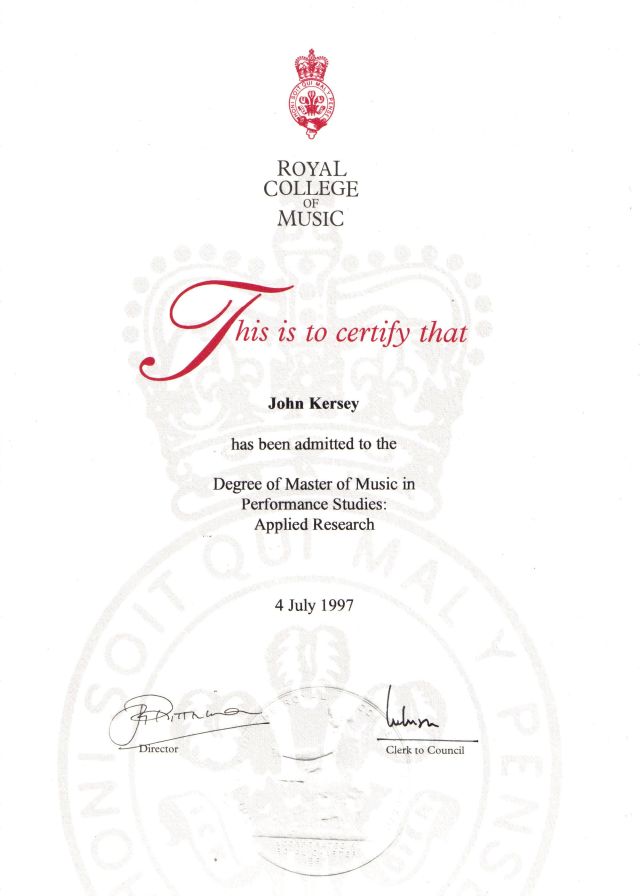

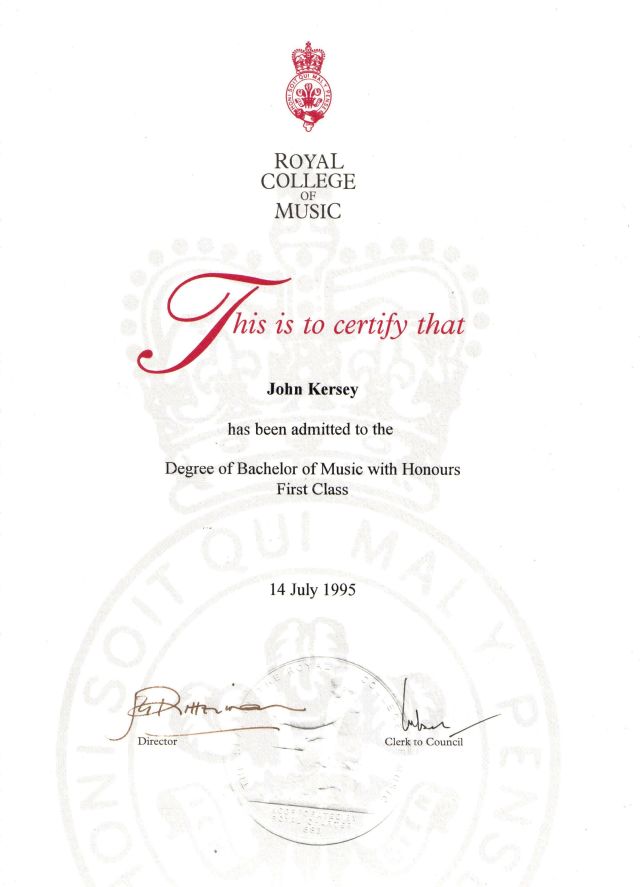

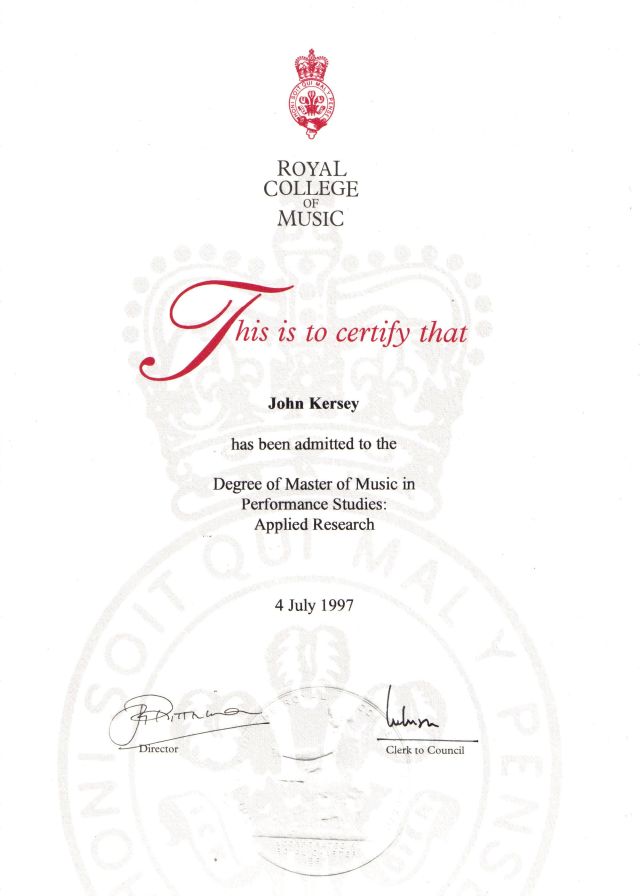

The Royal College of Music (RCM) is a public conservatoire in London, England, constituted by Royal Charter of Queen Victoria on 23 May 1883. The Royal Charter marked the RCM out as unique among conservatoires at that time, in that it was given the power in its own right to confer the degrees of Bachelor, Master and Doctor in Music either after examination or honoris causa. The RCM first used these powers in 1933 when it conferred the degree of Doctor of Music in the Royal College of Music, honoris causa, upon HM Queen Mary. From then until 1982 this degree was conferred only on members of the Royal Family. The degree of Master of Music in the Royal College of Music was first awarded in the 1940s and that of Bachelor of Music in the Royal College of Music in 1995.

The Royal College of Music (RCM) is a public conservatoire in London, England, constituted by Royal Charter of Queen Victoria on 23 May 1883. The Royal Charter marked the RCM out as unique among conservatoires at that time, in that it was given the power in its own right to confer the degrees of Bachelor, Master and Doctor in Music either after examination or honoris causa. The RCM first used these powers in 1933 when it conferred the degree of Doctor of Music in the Royal College of Music, honoris causa, upon HM Queen Mary. From then until 1982 this degree was conferred only on members of the Royal Family. The degree of Master of Music in the Royal College of Music was first awarded in the 1940s and that of Bachelor of Music in the Royal College of Music in 1995.

I was associated with the RCM successively as a Junior Exhibitioner, undergraduate student, postgraduate student and Junior Fellow for eleven years, between 1987 and 1998. During my time there, the RCM maintained a pre-eminent place amongst the world’s conservatoires and its diverse student body, with many coming from overseas to study, reflected its international reputation for musical training. It was highly selective in its admissions processes, and entry was by competitive audition. The RCM was generally regarded as having the strongest piano faculty of the London conservatoires at that time, and it was exceptionally difficult for a British pianist to win a place there. Once there, the atmosphere was intense and at times highly competitive. The College had a close relationship with the Royal Family, reflecting the foundation of the RCM under the personal initiative of King Edward VII (when Prince of Wales), and during my time I was present during multiple official visits by HM the Queen, HM the Queen Mother and HRH the Prince of Wales.

The Local Authority Junior Exhibition Awards were scholarships awarded by the London boroughs that allowed musically gifted school pupils to begin their training at the London conservatoires alongside their regular schooling, by attending the conservatoires’ Junior Departments free of charge on a Saturday. These awards, too, were subject to competitive audition, and I was fortunate to win a London Borough of Enfield Junior Exhibition Award to the Royal College of Music in 1987. I was then aged fourteen, and, as a late starter, was only in my fourth year of piano lessons.

Prior to entering the RCM, I had spent a very enjoyable year studying privately with the concert pianist Paul Coker, who apart from his work as a soloist was Yehudi Menuhin’s accompanist. Paul was an alumnus of the RCM and it was at his suggestion that I applied to study with his professor, Yu Chun-Yee. This was still more of a challenge since Yu Chun-Yee did not teach regularly at the RCM Junior Department and only accepted two junior students in addition to his undergraduates and postgraduates. Having successfully auditioned for him, I found myself at the RCM twice a week; on Friday evenings for my piano lesson with Mr Yu, and then all day on Saturday for the other activities of the RCM Junior Department.

In all, I would study with Yu Chun-Yee for nine years. He had one of the finest analytical minds I have ever come across. He could be fiercely demanding, and was often quite right to be so in setting the highest of standards, but was also extremely supportive and expressed great confidence in my abilities. Under his guidance, I developed both as a musician and as a person, and his detailed and exacting approach to study and interpretation has remained a cardinal influence on me ever since. What I valued in particular was that he taught me how to work out the answers to musical and technical problems for myself, providing me with an interpreters’ toolkit that has served me well ever since. The transferability of this training to other aspects of life has also proved to be considerable.

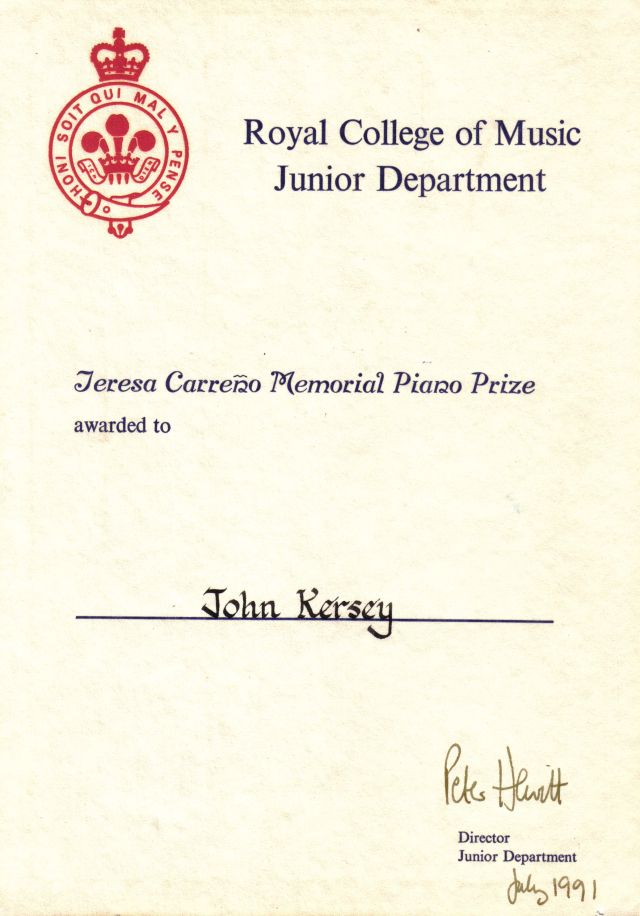

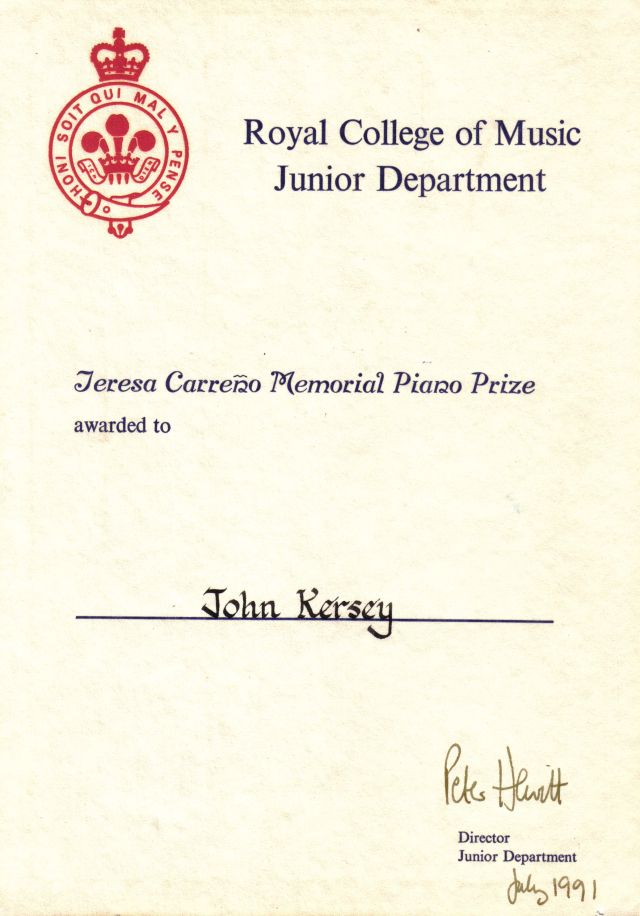

In my final year at the Junior Department I won the Teresa Carreño Memorial Piano Prize, the major competition award for pianists, and was also awarded the Constance Poupard Prize. After another set of competitive auditions, I was offered a place at the RCM to read for the Bachelor of Music degree, which was for the first time to be awarded by the RCM itself, rather than as previously by the University of London. This was a four year degree, in contrast to the usual three year duration of British first degrees.

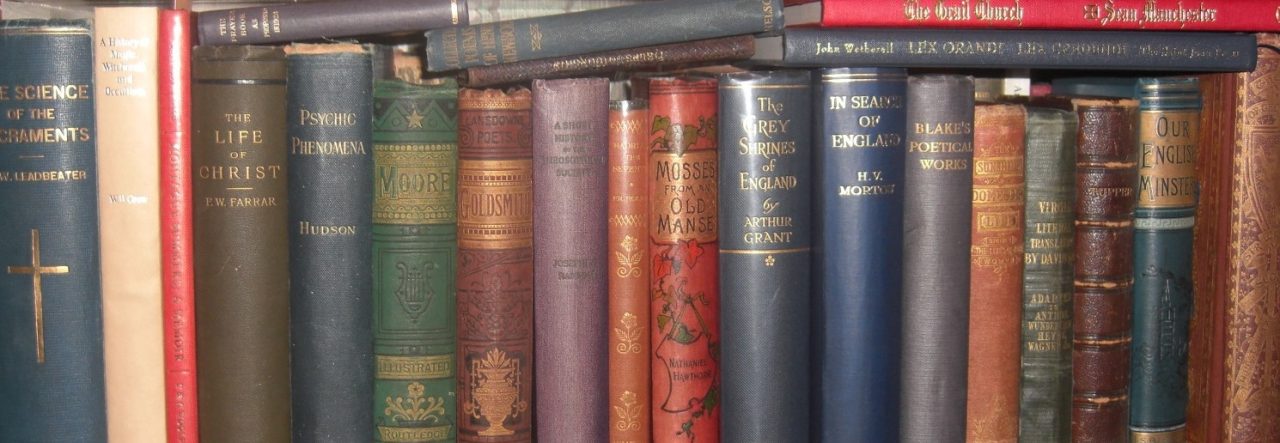

The great strength of studying at the RCM in those days was the fundamental emphasis on one-to-one tuition with leading professors. Most of those in the piano faculty were of many years’ standing and considerable eminence. Providing one made satisfactory progress, there was a great deal of freedom; obviously much time had to be devoted to individual practice and preparation for examinations and competitions, but outside this, there was the chance to read and listen widely, and to explore new repertoire with the aid of one of the best-stocked libraries of its kind. The overall ethos was dedicated to the applied musician. It was well suited to a pianist like myself who wanted in essence to be left alone to develop and grow under expert guidance, rather than to seek a more conventional “student experience”, and although I had a lively social life in those years, it was almost all outside the RCM. There was also a confidence in the RCM’s position as guardian of the traditions of Western art music, and in particular as the artistic home of several generations of distinguished English composers and pianists.

The RCM’s outlook of determined independence had been reinforced because at that time its closest rival, the Royal Academy of Music (RAM), had mounted what was in effect a takeover bid for the RCM. This seemed for a time to have government support. The RCM resisted the resulting pressure to create a London “superconservatoire” fiercely, and other than a joint vocal faculty with the RAM which lasted for a few years before being abandoned, was successful in maintaining its separate identity.

The RAM had deliberately jettisoned the conservatoire tradition that it had inherited in favour of a bid to create a “centre of excellence” on the model of Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute. This involved inter alia a reduction in student numbers, an academic partnership with King’s College, London, and an emphasis on masterclasses by international classical superstars, despite complaints that these were disruptive to first study teaching. In contrast to the RCM’s emphasis on the codified Western tradition, the RAM had also begun to teach jazz. Whilst I greatly enjoyed listening to jazz (and was a member of Ronnie Scott’s club for several years), I did not take the view that it should be taught in conservatoires or given equal standing with the interpretation of codified music. Largely out of a sense of obligation, I had auditioned for the RAM, but disliked the atmosphere and approach strongly, and never seriously considered studying there.

It was in this context that the RCM had decided to exercise its own degree-granting powers in respect of the new Bachelor of Music programme, which was introduced in 1991. When I was able to add input to the RCM’s direction – chiefly as a member of student review panels for my degree courses, as well as more informally in conversation with members of the administration – I sought to argue for the vision of the conservatoire in its historic context as a wholly independent entity dedicated to applied music, separate both from the university sector and the wider higher education establishment. This was a view that also enjoyed support among a significant number of the RCM’s staff, but that was increasingly coming to be seen as reactionary and anachronistic given the prevailing political winds.

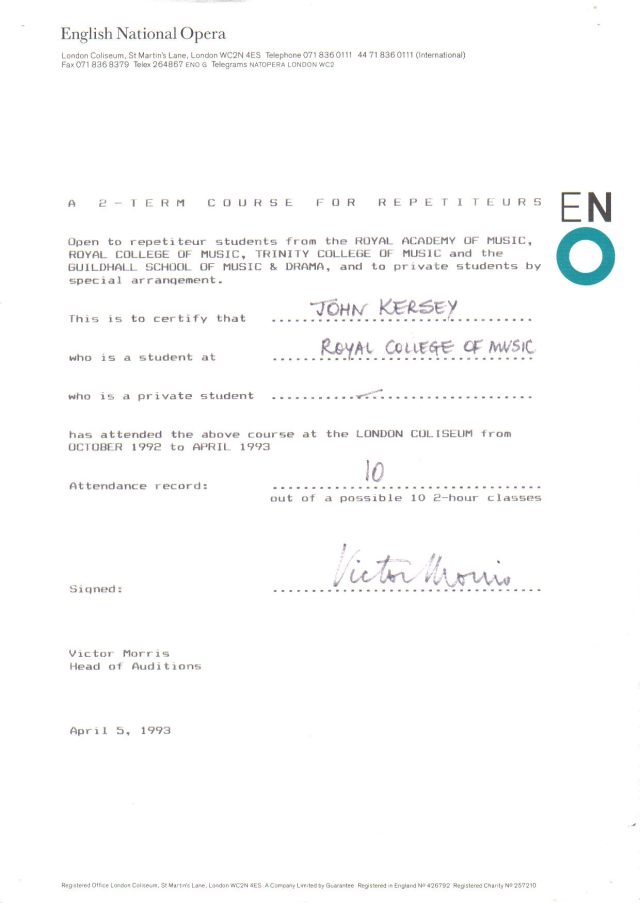

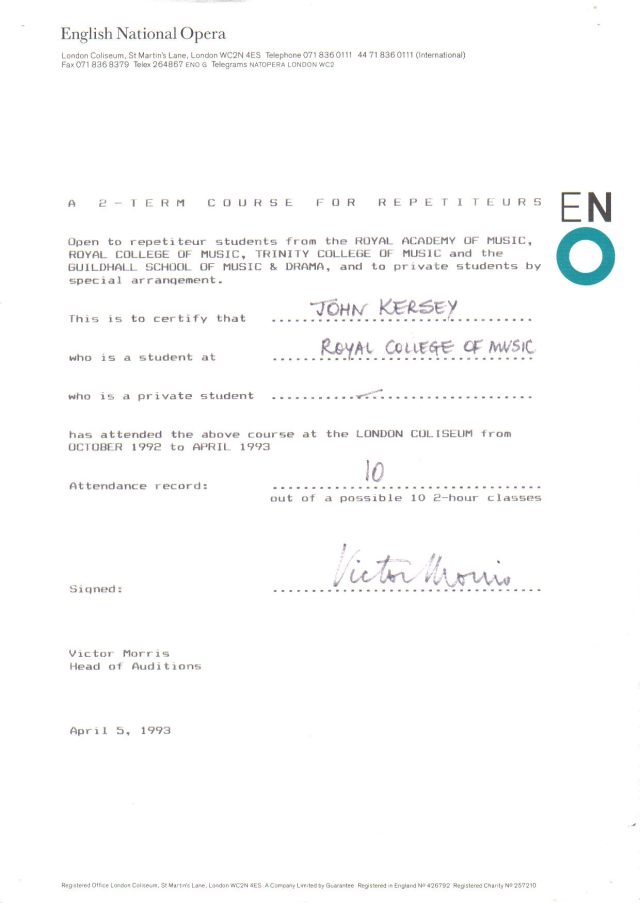

During my second year at the RCM, I was given the opportunity concurrently to undertake the Répétiteurs’ Course at English National Opera, which was usually open only to postgraduates. Not only was this fascinating and useful, it also carried with it a free rehearsal pass to all of ENO’s productions. I spent a good deal of time there during the year immersing myself in some glorious music-making, of which a marvellous and innovative production of Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel made a particular impression.

My studies at the RCM were pursued alongside a good deal of professional freelance work as a pianist and organist. Both as soloist and as a member of various duo partnerships, I played concerts at music clubs and societies around the country and also worked as a choral accompanist and pianist for musical theatre. One of my duos led to my playing on several occasions for the cellist William Pleeth at his home in north London. I found Pleeth’s energetic approach fascinating and loved his passionate, committed engagement with the music. Of course he was well-known as the teacher of Jacqueline du Pré, and a further close connexion with the circle of du Pré and Finzi was my supervisor at the RCM, the composer Jeremy Dale Roberts, who encouraged my developing interest in British music of the twentieth-century. Some years later, I would meet another member of the Finzi circle, the poet Ursula Vaughan Williams, when my duo partner and I gave the first performance of the song cycle All the Future Days in which the composer Jonathan Dove set her poems.

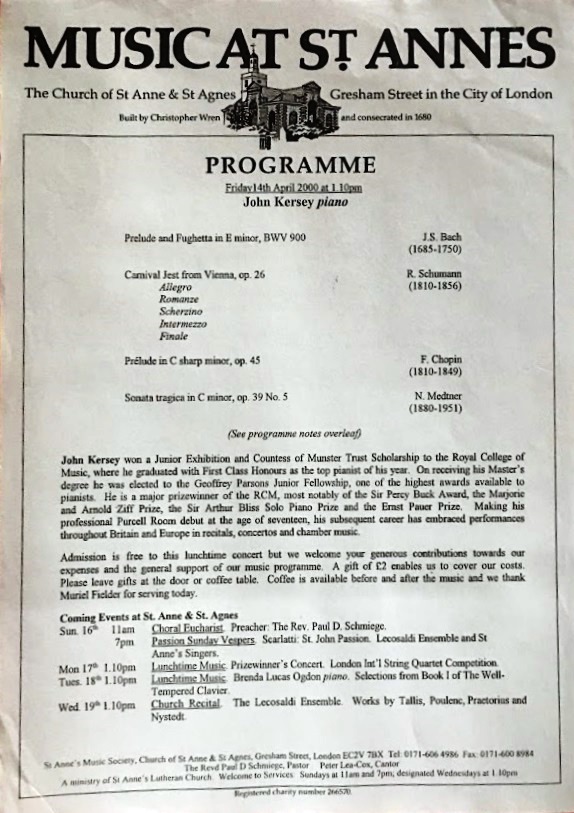

I was continuing to develop as a pianist, and several key performances in RCM concerts included Rachmaninov’s Second Sonata in the original 1913 version, and his Symphonic Dances in the version for two pianos. As well as concerts, the RCM placed much emphasis on competitions, which are often seen as a means to gain exposure for young pianists. However, the competitive spirit did not sit well with me. Competitions were deeply opposed to my own philosophical approach to music and I thought they did a profound disservice to music itself. During my time at the RCM, I entered internal competitions largely out of a sense of obligation and without ever feeling that they brought out the best in my playing. I certainly had no inclination to enter external competitions or to play the international piano competition circuit. Notwithstanding this, I managed to win some of the RCM’s prizes and awards. At the end of my second year, I was awarded the Margot Hamilton Prize for piano and the prizes for second year techniques and practical skills. A year on, I won the third year examination prize for piano, the Pauer Prize.

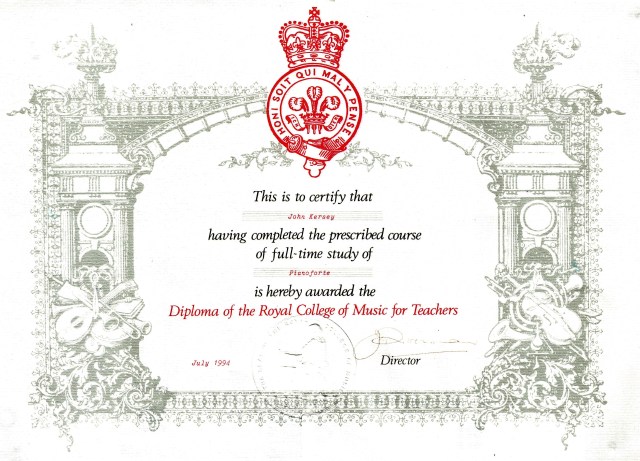

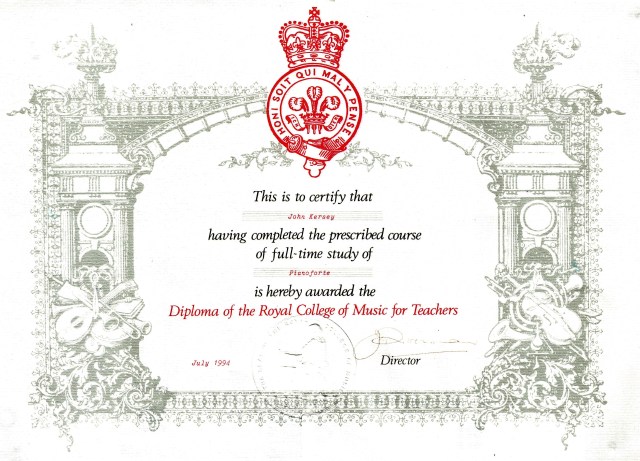

In addition to my degree studies, it was then a requirement for piano undergraduates that they should take the RCM’s teaching diploma. This was designated as the DipRCM(Teacher) for internal full-time RCM candidates, but followed the same syllabus and was examined to the same standard as the Associateship of the RCM in teaching that was available to external candidates. I attended some excellent Art of Teaching lectures with Peter Element, whose confident and authoritative approach appealed greatly to me, and the splendid Patricia Carroll, who I had known from the Junior Department. I was a successful candidate for the diploma at the end of my third year.

My interest in historical musicology was developed during my final year with a stimulating elective study in Advanced Performance Practice and Editorial Method under the organist and harpsichordist Gerald Gifford. As well as being a professor at the RCM, Gerald was also Fellow and Director of Music at Wolfson College, Cambridge, where I was invited to give a chamber music concert with fellow students that included Brahms’ wonderful late Clarinet Trio. Under Gerald’s guidance, I prepared a dissertation on cadenzas and related performance practice issues in Mozart’s piano concertos, focusing particularly on the C minor concerto K491. The RCM has Mozart’s autograph score of that work in its library, and the experience of seeing this familiar music in Mozart’s own handwriting left a deep impression on me.

Gerald Gifford was in charge of the RCM’s Master of Music programme in Performance Studies, which he had been responsible for designing. This combined advanced performance studies with research into cognate subjects. The programme had an excellent reputation and I had no reservation in applying for a place. Having been accepted, it remained only to undertake the remaining requirements for my BMus.

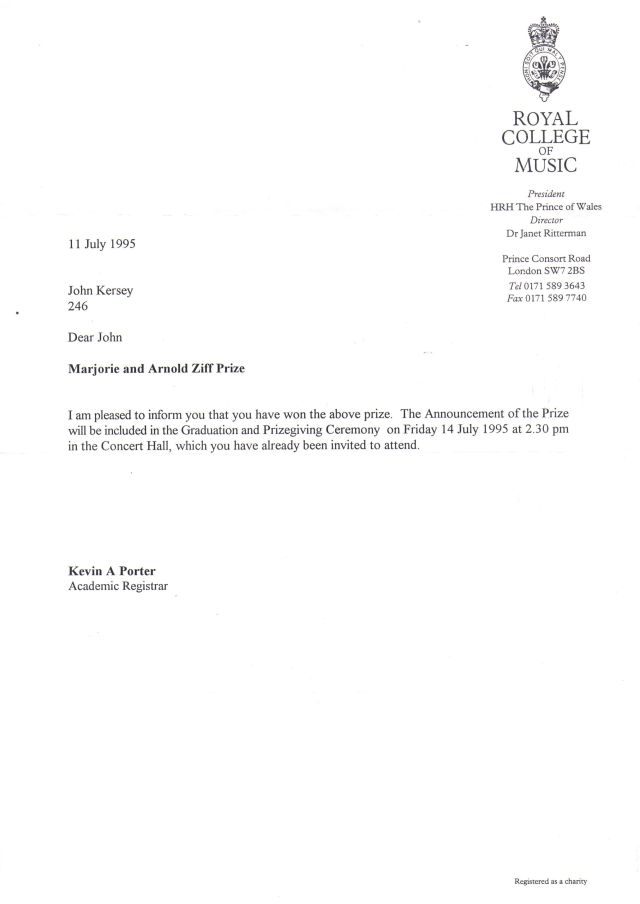

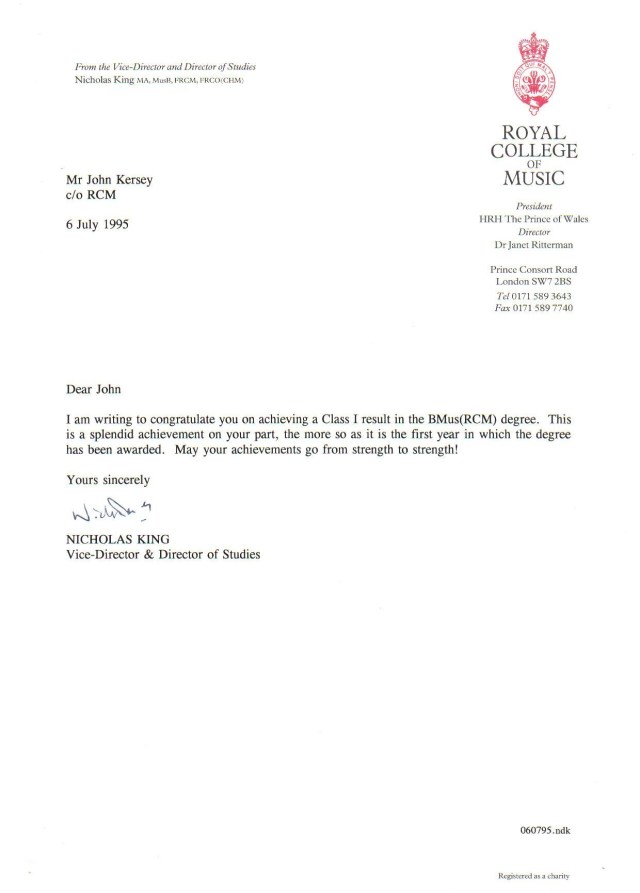

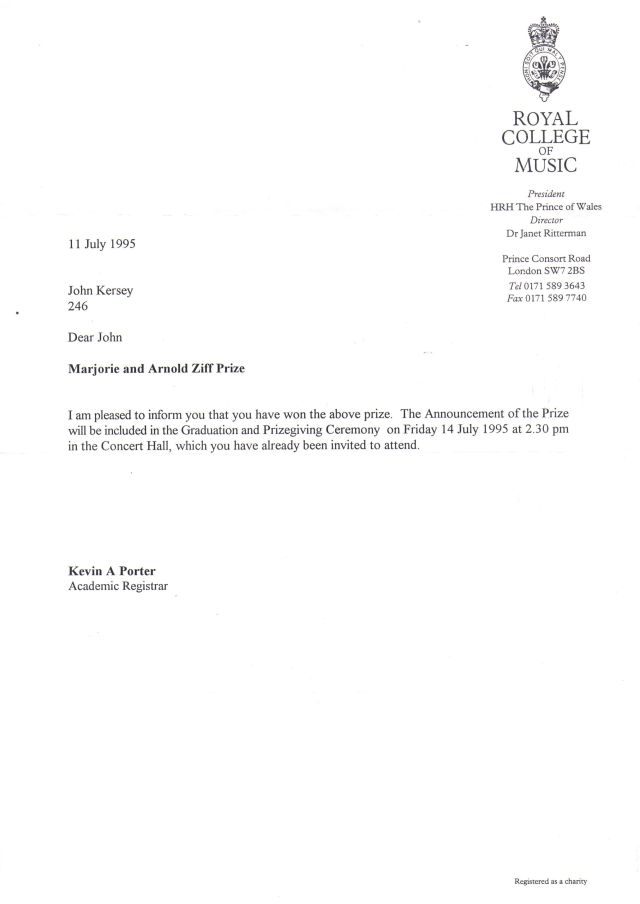

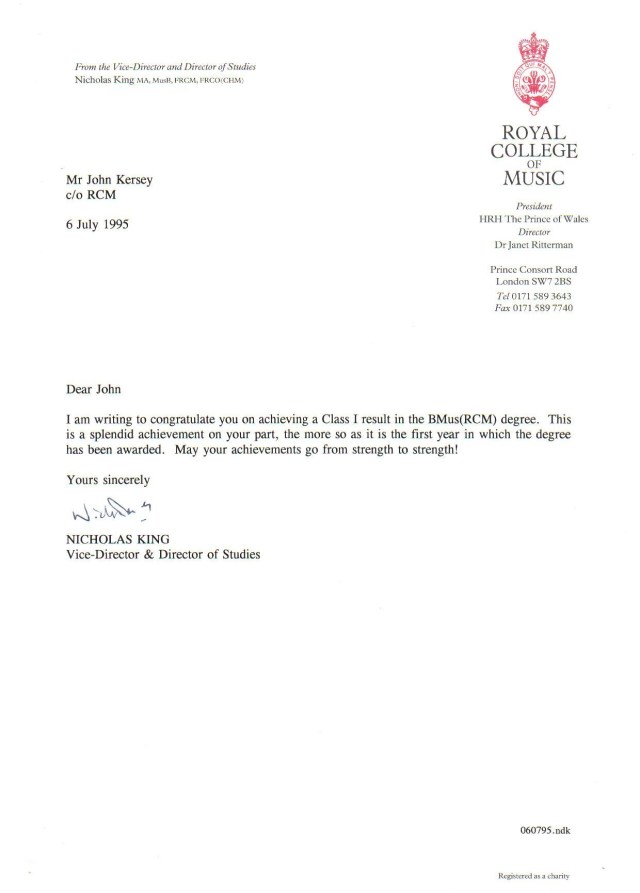

My degree studies culminated with a public final recital of some fifty minutes. I presented a varied programme including music by Bach, Berio, Schubert and Rachmaninov. I was awarded the Marjorie and Arnold Ziff Prize for the best piano final recital, and was the only first study pianist to be awarded a First. I was also the only first study pianist of the 1991 undergraduate intake to take First Class Honours overall in my degree.

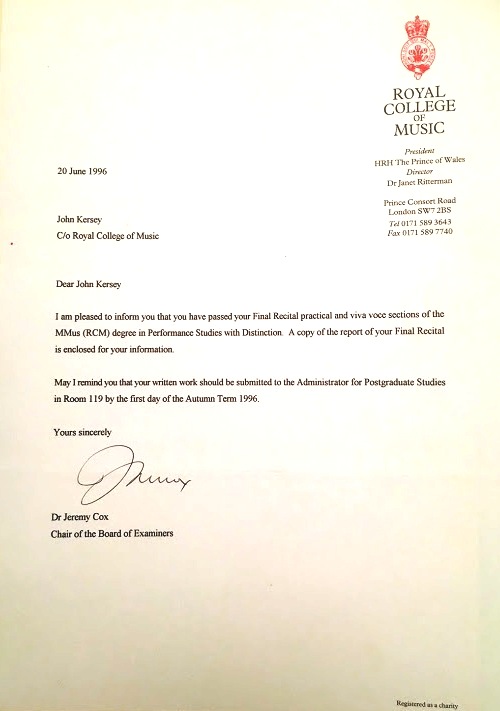

I received an official congratulatory letter from the RCM on achieving my First.

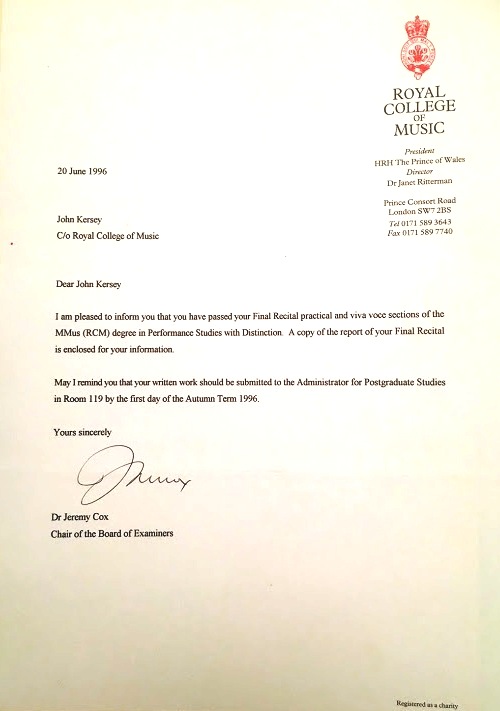

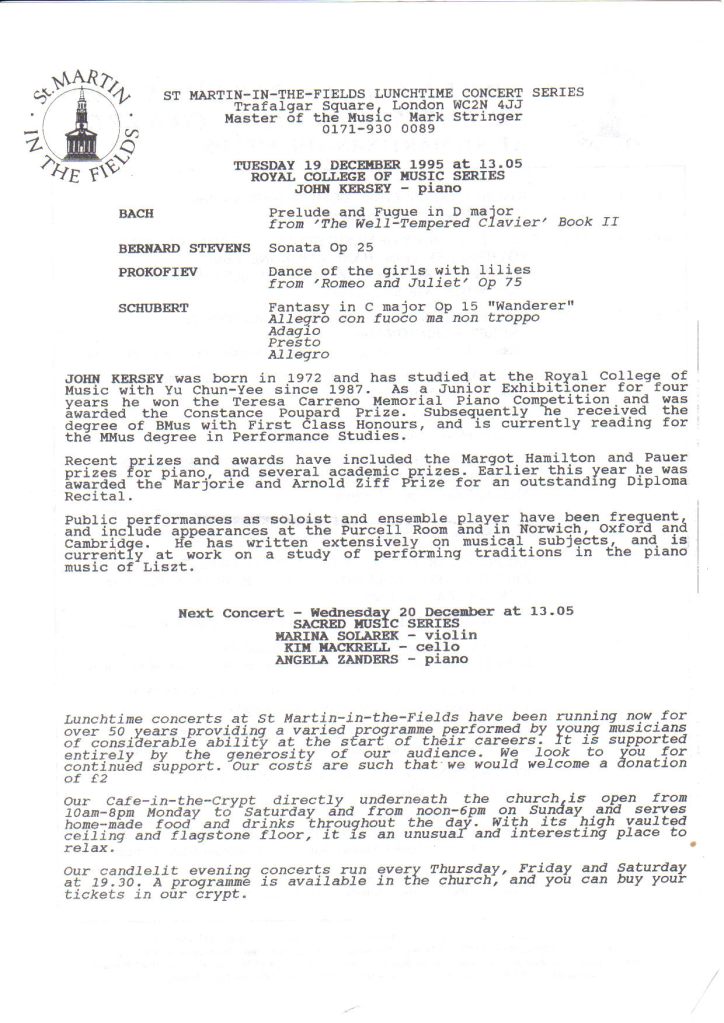

That autumn, I began my studies on the Master of Music programme. This required a final recital, a lecture recital and a research dissertation, with viva voce examinations on each component. The programme was unusually structured. The degree was not awarded until the end of the second year after enrolment, but formal studies extended only over thirteen months, leaving most of the second year vacant. This time, my research focused on performance practice in recordings of Liszt’s piano music by his pupils, and my lecture-recital was on aspects of rhythm in Alkan’s piano music. For my final recital, I presented two works, the Piano Sonata by the remarkable composer (and former professor at the RCM) Bernard Stevens (1916-83), and Schumann’s Humoreske. Both this and the viva that followed were awarded distinctions.

I was fortunate to be one of the winners of the RCM Concerto Trials, which offered the opportunity to play a concerto with one of the RCM orchestras. I had chosen Liszt’s Totentanz, a demanding and demonstrative virtuoso work, and performed this with the RCM Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrea Quinn on 23 January 1996. I chose to use the expanded performing edition by Liszt’s pupil Alexander Siloti, which adds a number of interesting passages to the original.

During the year, I won the Sir Arthur Bliss Solo Piano Prize and was also awarded the Bernard Stevens Performance Prize for performances of those composers’ piano sonatas. The Bliss Prize led to a recital at the West Road Concert Hall in Cambridge and a meeting with the composer’s widow, who wrote “your interpretation of the Bliss piano sonata is one which would, I know, have delighted the composer.” I was also awarded the Sir Percy Buck Prize for a postgraduate who had previously studied in the RCM Junior Department.

As I reached the end of my studies, Yu Chun-Yee told me that I had now arrived at the point where I could play anything in the pianist’s repertoire. He meant by this not that I would not have to work hard at whatever I had chosen to attempt, but that I now knew how to do that work and was in possession of the necessary interpretative skills, musicianship and technique. This was the fulfilment of what I had set out to do when I first began studying the piano seriously, and although I would subsequently seek advice from other professors when preparing for concerts, notably John Blakely and Yonty Solomon, I regarded my formal piano studies as now being complete.

I was notified that I had been successful in the Master of Music degree that autumn, and would await formal graduation the following summer.

The question inevitably arose as to what I should do next, both immediately in the eleven months that remained until my MMus would formally be awarded, and beyond this. There was the option of simply continuing (and hopefully expanding) the freelance performing work that I had been doing throughout my time at the RCM, but I also felt that I did not want to rule out opportunities for further research, which would require a continuing institutional affiliation.

In considering my options, I had to face the fact that the RCM was no longer the same institution that I had joined almost a decade earlier. The higher education funding and regulation authorities, driven by the universities and by ministers who neither understood nor were sympathetic to the conservatoire way of doing things, were no longer happy to see the RCM plough its own furrow, and the postgraduate provision had been particularly (and in my view unfairly) criticized. These criticisms seemed to me to be designed to curb the RCM’s independent viewpoint and fully integrate it into the higher education establishment. Although the RAM’s “centre of excellence” plans had not directly provided the model for what was to come, it was not difficult to see that the reformed RAM was more obviously suited to the new regime, and that the RCM was to be compelled in a similar direction. The first signs of this were an increase in administrative and bureaucratic requirements culminating in a fairly brutal round of staff departures. Two further changes that I considered key were the effective abolition of its alumni association*, and of the RCM Magazine. It seemed to me that these moves were attempts to keep a lid on staff and alumni dissent, which had previously proved a significant issue during the RAM’s period of radical change.

These changes were not happening in isolation. The British musical tradition was under attack from a press that considered it mediocre in comparison to the glitzier product on offer abroad. My chief research interests in rare music of the Romantic era, in piano performance history and in twentieth-century British tonal music were deeply unfashionable. It was also clear that the concert infrastructure that had supported British pianists for generations, in particular the music clubs and societies, was diminishing significantly as its members grew older, and there was an increasing demotic shallowness to the way in which classical music was now being sold to the public that did not sit well with me. As society itself became more consumerist and fixated upon youth, the virtues of maturity and reflection, which are cardinal to musical interpretation, all but disappeared from view. More practically, even pianos themselves were changing. The pianist is hypersensitive by nature; so is ivory, which is the ideal material for piano keys since it not only absorbs perspiration but is highly responsive. In the wake of the international ban on ivory, the top manufacturers had turned to making piano keys from resins and various forms of plastic instead, which lacked the responsiveness of ivory and also left drips of perspiration on their surfaces. For me, it was like replacing gold with brass.

That autumn, I had the opportunity to undertake a term of postgraduate research at Cambridge, which I have written about elsewhere. After Christmas, I returned to a life of freelance musical engagements in London, and before long also began to do some voluntary work at the RCM Library, where I covered staff vacancies and undertook several cataloguing projects of historic materials concerning British musicians of the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries. The Library had not yet been computerized, and was still using handwritten card indices and catalogues. This suited me well, since I had an innate dislike of computers, and my time there was both happy and productive.

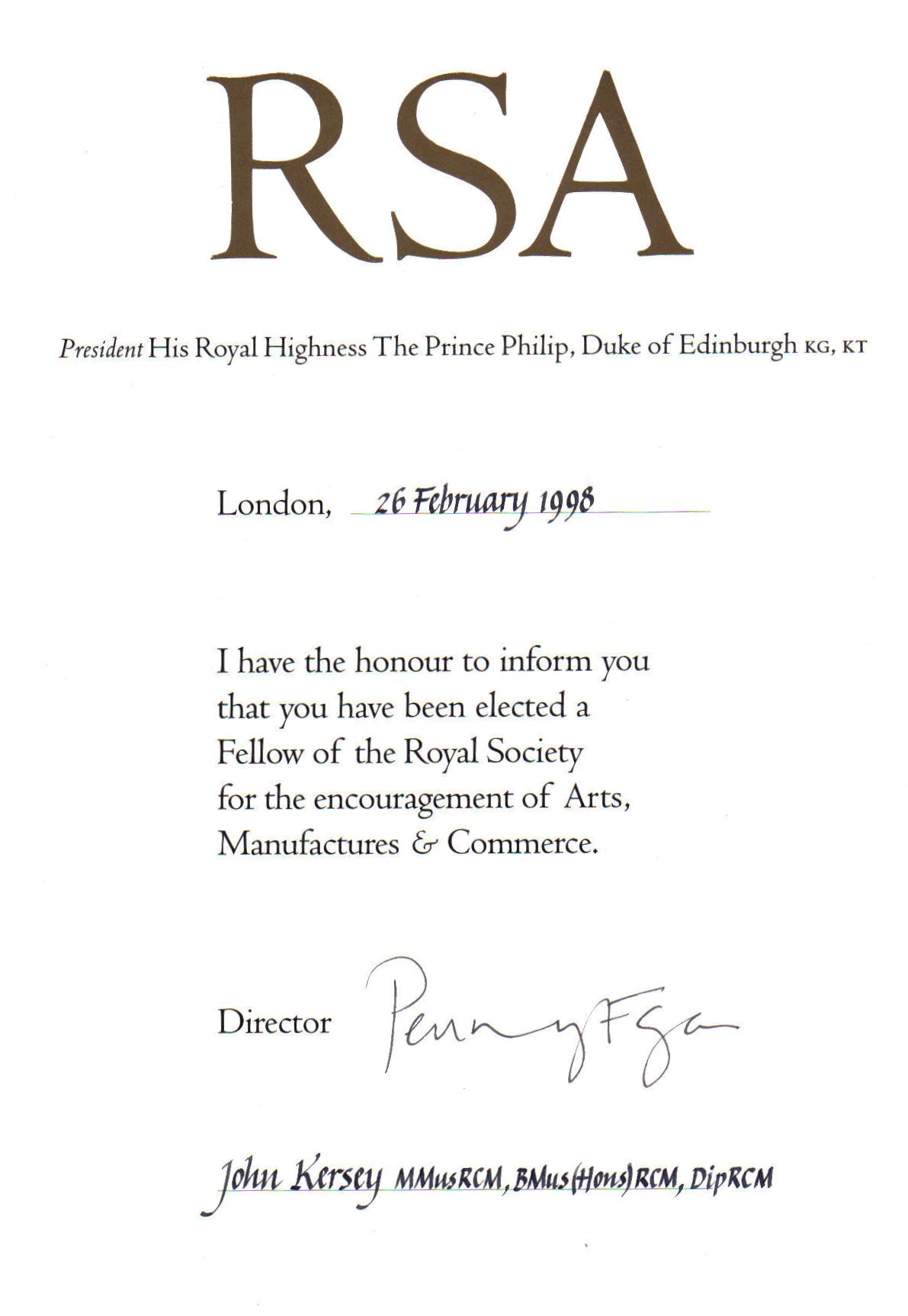

A new development at the RCM was the introduction of Junior Fellowships. These were intended to support young musicians after the conclusion of formal studies and their holders were attached to the staff rather than to the student body. I was offered the Geoffrey Parsons Junior Fellowship for the academic year 1997-98, and as a result was presented to HRH the Prince of Wales, President of the RCM.

There was a sense in which my Junior Fellowship year felt valedictory as soon as it had begun, and I was certainly aware that I needed to make the most of all the opportunities that it offered. I undertook a great variety of ensemble and accompaniment work, and also toured with the RCM in Portugal, playing before the President and Prime Minister there at the British Embassy. All this was combined with my existing external commitments as a performing musician, to which I had now added regular work as a record critic and a teaching position at a nearby sixth-form college. I enjoyed the atmosphere of the RCM’s Senior Common Room, and formed good relationships with a number of the professors.

Although Junior Fellows were not permitted to perform as soloists in RCM concerts, I considered it vital that I should continue my work as a solo pianist alongside my other commitments. The RCM had recently built a professional recording studio, and I was given the opportunity to record a CD of some works of my choice there. I devised a programme of twentieth-century British piano sonatas by Arthur Bliss, Bernard Stevens and Stanley Bate. Bate’s unpublished second piano sonata was part of his manuscript collection now in the RCM Library. I prepared the work from the composer’s autograph, and played it in concert at St Martin-in-the-Fields. Although Bate was an accomplished pianist who was often to be heard in his own works, there was no record of him having performed this sonata in public, and accordingly both my performance and recording were premières.

I returned to the RCM on a few occasions in the year after my Junior Fellowship. I was delighted to be asked back to join a group of postgraduates in playing the demanding piano part in Webern’s arrangement of Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony for the Pierrot Lunaire combination of instruments, and much enjoyed the resulting performance. I also undertook some occasional deputy teaching to cover the absence of one of the keyboard professors. This, however, was to be my final involvement with the RCM.

In my view, the RCM as it is now has changed immensely from the institution as it was during my time. The change has not merely been of a kind that one would normally expect of an institution over time but has been radical and at times iconoclastic in response to external pressures on higher education, meaning that the concept of what the RCM is and how it fulfils its mission now is quite different from the conservatoire tradition that I experienced and inherited there. My loyalties continue to remain with the principles that the RCM upheld during my era, and as an old Royal Collegian, I have tried to bring those principles to bear on my other work in music and education since then.

* The initial alumni and former staff association of the RCM was the RCM Union, founded in 1906, which also included as members all current students and staff of the RCM. The RCM Union was the body responsible for the RCM Magazine. In 1992, the RCM Union was closed. The alumni association element was continued by a new RCM Society, which like the RCM Union was a subscription-based association, but in 2001 this was repurposed as a non-subscription body of wider scope including all former students and staff. In 2009 it was abolished altogether. The RCM Magazine was initially taken over by the RCM Society but was discontinued in 1994, to be replaced by an Annual Review that was issued as an official publication of the RCM’s governing administration rather than being under the editorship of a member of the professorial staff as had been the case with the RCM Magazine.

The

The