ACADEMICAL DRESS OF MUSIC COLLEGES AND SOCIETIES OF MUSICIANS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

with notes on certain other Institutions

Second Edition

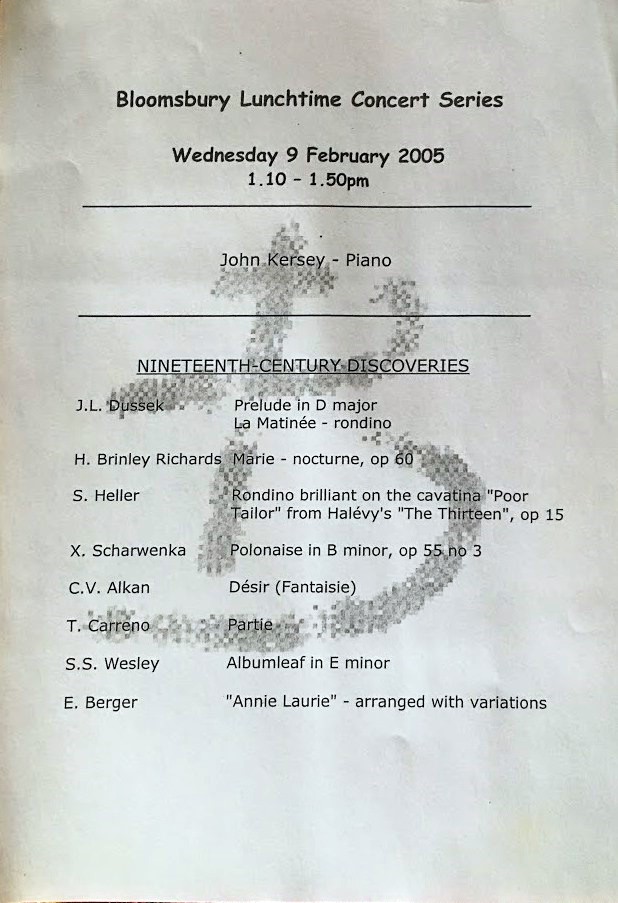

John Kersey

First edition (co-authored with Nicholas Groves) published in 2002 by The Burgon Society.

Second edition published 2007 by European-American University Press.

Copyright © 2002, 2005, 2007, John Kersey.

John Kersey asserts the moral right to be identified as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. This electronic file may not be sold or resold in any manner whatsoever; it is designated for free distribution and no charge may be made for access to it.

Introduction

This work is a celebration of the many British institutions dedicated to the art of musical performance and composition (hereafter referred to by the American term of “applied music”) and the robes that they have used to signify their corporate identities and record the distinctions of their members.

Musical education in Britain has a much older history within the conservatoire system than within universities, for, despite the fact that university degrees had been offered in Music since Cambridge’s earliest known example of 1463, no tuition was offered by the universities for such degrees, their role being confined to examining the work presented by external candidates (who were not admitted as members of the university; thus creating the absurd situation, in the case of Oxford DMus and some Cambridge MusD graduates of their having to sit for a pass BA degree in some other subject before they could take up a teaching post at their respective universities. Thus both Sir William Harris (who was DMus Oxon by examination) and Dr H.K. Andrews (who was DMus Oxon by incorporation from the DMus of Trinity College, Dublin) had to take the Oxford degree of BA upon becoming organists of New College, Oxford. Indeed, the work of the conservatoires formerly included (as well as preparation of candidates for their own diploma awards) preparation for these external university degrees. This situation persisted until the middle years of the twentieth-century (and external degrees in music continued to be offered beyond then) at which point the universities, perhaps spurred on by the increasing success of the conservatoires, were eventually minded to form teaching faculties in music. Even then, the nature of the university undergraduate music courses, especially at the ancient universities, was usually such as to exclude performance and free composition almost entirely in favour of studies in music history, analysis and pastiche composition, and at the graduate level to wholly reject the admission of work in applied music to research degrees.

Fortunately, the more progressive university courses now firmly establish applied music within a comprehensive study of the subject at undergraduate level, and several institutions have now introduced the American-originated DMA degree as an alternative to the PhD (although few so far grant it equal status). Meanwhile, the most senior of the conservatoires, now drawing on over a hundred years of experience of teaching music and with some of the most illustrious names in the profession numbered among their alumni, have introduced searching and broadly-based undergraduate courses that are designed to meet the needs of the dynamic musical profession of today, at the same time as developing international research profiles in their fields of expertise; the DMusRCM programme being a leading example of a progressive higher doctorate that admits cognate work in applied music in addition to the customary research thesis to its requirements.

There are several distinct categories of institution that may be found within these pages. These may be defined as the conservatoire, which to all intents and purposes is an institution offering full-time courses devoted primarily to applied music (including those of graduate status and beyond) that is national or international in its reputation, outlook and level of activity, and which may be seen as a specialist university-level institute. There are also smaller bodies, often having originally performed some of the teaching functions of a conservatoire, but whose activities may now be confined to functioning as examining boards. Then there are those institutions that have been founded solely as examining boards and whose main work is to be found in the provision of examinations from local graded schemes to diploma level. Lastly, there are numerous learned societies of musicians, often founded with a particular specialism within the field in mind, which encourage musical performance through their activities and also promote debate and fellowship among their members. It will generally be apparent to the reader into which category a particular institution falls.

The prescription of Academical Dress is a practice inherited by musical institutions from the universities, and there is evidence that a number of institutions (notably the Tonic Sol-Fa College of Music and the Victoria College of Music) had introduced their own robes by the late nineteenth-century. Others were slower to take up the practice, and it used to be said (up to the 1960s) that graduates of the London Royal Schools would take the diplomas of the Tonic Sol-Fa College simply so that they might have a hood to wear! There is enormous diversity in the robes used, from the elaborate and quasi-doctoral to the simple and self-effacing, and the systems involved include fully logical (eg. NSCM) as well as semi-logical (eg. NMSM) examples. The GSMD is unusual in that it uses the American system of chevrons on the hood and sleeve-bars for the GGSM. It may also be seen that some institutions preserve an old tradition of Academical Dress, whereby the highest grades of award are granted fur on their hoods. This recalls the original system whereby doctoral hoods were granted fur, which persisted (at Cambridge) well into the nineteenth-century but can now only be found (amongst UK institutions) on the DrRCA hood of the Royal College of Art. The specifications of the robes is given using the Groves system of classification, which is explained before the institutional entries and offers an easy method of identifying a particular style of robe. Headgear is generally excluded from this study, but is only rarely prescribed by the institutions.

The inclusion of institutions within this work is subject to several criteria. In the first place, the institutions included in the main section have awarded their own autonomous qualifications or grades of membership as independent colleges, without being part of the mainstream university system. Secondly, the institutions included in this section have their own distinct scheme of Academical Dress. A few colleges whose status as far as conferring diplomas and prescribing Academical Dress is uncertain have been included, generally in footnotes to the main text. We have also included certain other institutions of interest; mainly the principal overseas music colleges. Where an institution in the first section awards, as well as its own diplomas, qualifications validated by an external body such as an university, but there is no difference in the robes prescribed by that institution from the usual robes of that university, the robes in question are omitted from our survey. Similarly, where an award is bestowed both ordinarily and honoris causa, but there is no difference in the robes, only the ordinary award is listed. Webpages and contact details were correct as at July 2004, but readers should be warned that these tend to change frequently in the case of some institutions.

During the course of preparing this work, a number of difficulties have been encountered on account of the extremely obscure nature of some of the bodies involved and the paucity of information available on them. I would be most grateful for any further information from readers on these institutions for inclusion in a subsequent edition.

It should be noted that the opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, except where otherwise indicated.

The first edition of this book was jointly authored by Nicholas Groves and myself, in that the text was principally my work but was based on joint research carried out by Nick and myself. Shortly after it had been published, new information came to light that suggested that, at least, a further booklet of addenda and corrigenda should be prepared, and this was duly proposed by Nick to the original publishers, the Burgon Society, of which he was at that time a Council member. On 2 February 2004, Nick wrote to me, “I raised the question of the music book addenda/corrigenda at Council on Saturday – it was felt that a duplicated pamphlet was not desirable, but that a second edition can be produced in a year’s time!” I duly prepared this second edition with the invaluable assistance of Nick’s research notes and comments. This resulted in a much improved book, which included a number of newly included specifications and institutions. The concluding section, which had included a number of institutions that were beyond the proper scope of the work, was also rationalized.

As late as 10 March 2005, Nick was writing to me, “The Society feels very strongly that it must remain as a BS [Burgon Society] publication.” (this in response to my suggestion that as an alternative the second edition might be issued online by the London Society for Musicological Research in which Nick and I were both at that time involved as council members). The second edition had by then been completed by me and was sent to Nick for submission to the publishers.

In the ensuing days, Nick decided, without informing me of his reasons, to withdraw his support from the book completely. The Burgon Society colluded with him and furthermore bizarrely denied ever having agreed to support the second edition, which nevertheless they attempted to suppress through ill-founded legal threats. I took the view that this was entirely disreputable conduct that reflected very poorly on those concerned, and duly terminated my connexions with them. However, it has been my determination that their actions should not prevent this potentially useful work from seeing the light of day.

John Kersey

London

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the following for their advice, information and encouragement, which has proved invaluable in the preparation of this book: Dr Michael Barkl, Dr John Birch, Maureen Forster, Revd. Philip Goff, Revd. Canon Dr Mark Gretason, Nicholas Groves, Dr Donald Heath, Dr Peter Horton, Dr Stephen James, Dr Frances Knight, Andrew Linley, Philip Lowe, Dr John Lundy, William McArton, Edward Moroney, Andrew Nardone, Br. Dr Michael Powell cj, Dr Robin Rees, Dr Stuart Sime, Amanda Townsend, Dr Terry Worroll, Ede and Ravenscroft Ltd., Wm. Northam and Son and the websites of the organisations included; also various directories of music, notably the various editions of Who’s Who in Music and the British Music Education Yearbook. The assistance of numerous works on Academical Dress by such authors as Wood, Haycraft, Stringer, Smith and Sheard, and Shaw, amongst others, has been invaluable.

I have endeavoured to acknowledge the sources of information contained in this book. If I have unintentionally omitted to do so, I apologise for this and will gladly correct this information in subsequent editions.

Hood and Gown Classification

This is the Groves system, designed to make each hood or gown pattern instantly recognisable. Certain distinctions have been simplified for ease of classification; Cambridge MusD and St Andrews doctors are recorded as identical here and all full hoods with a square cape are recorded as [f1] except Glasgow’s hood, which is distinctive.

Simple hoods have a cowl only and are designated [s]. Full hoods are those with both cape and cowl, and are designated [f]. A third category is [a] which is the Aberdeen type of hood consisting of a cape only.

Gowns are defined as [u] undergraduate, [b] bachelor, [m] master and [d] doctor.

An explanation of the different shapes of hood and gown may be found in Nicholas Groves’ Key to the Identification of Academic Hoods of the British Isles (published by the Burgon Society).

Simple hoods

s1: Oxford simple

s2: Burgon

s3: Belfast

s4: Edinburgh

s5: Wales bachelors

s6: Leicester bachelors

s7: Leeds

s8: Sussex

s9: Manchester

s10: Aston

s11: Glasgow Caledonian

Full hoods

f1: Cambridge

f2: Dublin

f3: London

f4: Durham doctors

f5: Oxford doctors

f6: Durham BA

f7: Durham BCL etc.

f8: Edinburgh DD

f9: Glasgow

f10: NCDAD

f11: Warham Guild

f12: St Andrews

f13: UMIST doctors

f14: American Intercollegiate Code doctors

Aberdeen hoods

a1: Aberdeen

a2: Leicester masters

a3: Kent

a4: East Anglia

a5: Leicester doctors

a6: Dundee

Undergraduate gowns

u1: Cambridge

u2: Oxford scholars

u3: London

u4: Durham

u5: Oxford commoners

u6: Sussex

u7: East Anglia

Bachelors’ gowns

b1: Oxford BA

b2: Cambridge BA

b3: Cambridge MB etc.

b4: London BA

b5: Durham BA

b6: Wales BA

b7: Bath BA

b8: Imperial College diplomas

b9: Belfast BA

b10: Dublin BA

b11: Reading BA

b12: Sussex BA

Masters’ gowns

m1: Oxford MA

m2: Cambridge MA

m3: Dublin MA

m4: Wales MA

m5: London MA

m6: Manchester MA

m7: Leeds MA

m8: Leicester MA

m9: Bristol MA

m10: CNAA MA

m11: Lancaster MA

m12: St Andrews/Glasgow MA

m13: Liverpool MA

m14: Open University (all degrees)

m15: Warwick MA

m16: Bath MA

m17: Sussex MA

Doctors’ gowns/robes

d1: Cambridge/London

d2: Oxford

d3: Cambridge MusD/St Andrews

d4: Oxford lay/gimp gown

d5: Oxford convocation habit

d6: Sussex

MUSIC COLLEGES AND SOCIETIES OF MUSICIANS

The Academy of St Cecilia

Founded 1999

Master: Mark Johnson

71c, Mandrake Road, London SW17 7PX

020 8265 6703

www:academyofsaintcecilia.com

The Academy of St Cecilia was founded as a learned and social society with a particular interest in Early Music, loosely interpreted as music before 1825. Since its foundation it has included a number of distinguished figures in the field of Early Music amongst its Honorary Fellows, and has enjoyed the association of patrons who include James Bowman, Monica Huggett, Naji Hakim, Professor Reinhard Strohm (Heather Professor of Music, Oxford University) and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies. The Master of the Academy, Mark Johnson, has pursued a career in music education and is a singer with professional choirs.

The activities of the Academy centre upon the UK, but in recent years, in response to a continuing growth in membership, Regional Representatives have been appointed for Australia and Canada. In the UK, the Academy’s twice yearly General Meetings are usually held in London’s historic Church of St Margaret, Lothbury, where the formal business of the Academy is followed by musical entertainment of a high standard. This has recently included vocal and organ recitals, choral concerts and illustrated lectures.

The Academy produces a regular newsletter, Vox, which includes articles written by members and relevant items of interest.

The honorary award of FASC is reserved for heads, officers and staff of musical organisations, universities, examining bodies etc. who have made a significant contribution to early music.

Since 2002 the Academy has established an Early Music Advisory Panel consisting of Honorary Fellows, who are available to answer specialist questions in that area.

Academical Dress

Gowns:

These are common to all; which is worn depends on the type of function being attended.

Performing: Cambridge BA in black [b2], with gold cord around the arm-slit and along the facings. There is a cord and button on the yoke.

Festal: Oxford MA in black [m2], with gold cord along the facings and around the armholes. There is a cord and button on the yoke.

Hoods:

FASC (until 2000): dark blue, lined and the cape bound 2” old gold [f9].

FASC (honorary & foundation Fellows only until 2000; all Fellows since 2000): as FASC above, but the cowl faced 3” cerise also.

AASC (since 2003): dark blue, lined and bound old gold [s2].

Members of Council: as for FASC (post-2000) but with the body of the hood in blue brocade.

The Academy also awarded one Honorary Membership in 2001, but that award does not carry the right to academical dress.

A scheme of corporate robes for choirs was introduced in 2003; this is as follows:

Gown:

A black gown with gold cord on the sleeve and the yoke [u5].

The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music

Founded 1889

Chief Executive: Richard Morris

14 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3JG

020 7636 5400

www:abrsm.ac.uk

The Associated Board arose out of a desire by the Royal College and Royal Academy and their respective Director and Principal, Sir George Grove and Sir Alexander Mackenzie, to join together to provide an examining body of integrity and high standards. The efforts of this body were directed towards a rigorous system of local graded examinations, of whose first syllabus it was said that the standard was so high “…that the certificate granted may be regarded as a distinction worthy of attainment.” Originally the minimum age at which candidates might be presented for the examinations of the Board was twelve, with the examinations divided into Junior and Senior grades, but soon a demand for examinations suitable for younger children caused the introduction of a new system of division into Lower, Higher, Intermediate and Advanced sections. This system persisted until 1949, when the present system of division into Grades I to VIII was introduced. In recent years the Advanced Certificate has been introduced beyond Grade VIII.

In 1947 the other Royal Schools, the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Manchester College, also became members of the Associated Board.

The diplomas of the Royal Schools have an interesting history. The distinction Graduate of the Royal Schools of Music was introduced at the RAM and RCM for those who had completed the searching full-time course of three years’ duration and of graduate level that was originally designed for intending teachers. From 1975 until its final award in 1995 it was awarded with classed honours rather than by the previous system of unclassed pass, pass with merit and pass with distinction. The diploma of LRSM (originally LAB) was introduced as an overseas equivalent to the diplomas of ARCM and LRAM and was awarded in all the normal divisions of performing and teaching.

In the recent past the diplomas of the Royal Schools have been re-designated, with the previous diplomas of ARCM, DipRCM (Teacher), LRAM (which, however, remains available to internal RAM students) and the former LRSM (for overseas candidates) all being replaced by a new LRSM diploma that is available to UK as well as overseas candidates. The recently-introduced diplomas of DipABRSM and FRSM are now also available by examination. It will be seen that in the Academical Dress of the ABRSM the RAM colour of scarlet is allied to the RCM colour of royal blue.

Since its outset the Board has maintained a panel of examiners largely drawn from the staff of the Royal Schools and their former students. It has in recent years expanded its range of examinations to include early grades in jazz piano.

Academical Dress

Gown:

a black stuff gown of Oxford BA pattern [b1].

Hoods:

ARSM: scarlet, lined black, with a gold tipping [a1]

LRSM: scarlet, lined white watered, with a gold tipping [a1]. This diploma was originally known as LAB (Licentiate of the Associated Board).

DipABRSM (awarded post-2000 only): scarlet, faced 3” royal blue, with a reversed (to shew royal blue) neckband [f1].

GRSM: scarlet russell cord, faced 3” royal blue silk [f1]; diploma last awarded 1995.

FRSM (awarded post-2000 only): scarlet, lined royal blue, with a reversed neckband [s2].

Academical Dress for GRSM was introduced at some point between 1948 and 1970, and for LRSM after 1970.

Association of Church Musicians

Now incorporated into the North and Midlands School of Music (q.v.)

Revd. Stephen Callander writes:

“The ACM evolved from a small group of singers in Worcester in the early 1980s and was incorporated into the NMSM in 1999. The last Fellows were created just before the incorporation. The ACM never had more than 20 members.

The original Foundation Fellows’ hood was Aberdeen shape [a1], Mary blue, fully lined red brocade. The inside of the “cowl” was faced 1″ fur. Fellows were the same sans fur. Latterly the hoods were changed to London shape [f3], dark blue, fully lined/bound pale pink.”

The ACM was founded in 1984 by Revd. Roger Francis.

Birmingham Conservatoire

Founded 1859 as the Birmingham and Midland Institute School of Music, often known simply as the Birmingham School of Music. Re-constituted in 1886.

From 1969-93 the BSM was part of the City of Birmingham Polytechnic.

In 1993, the BSM became the Birmingham Conservatoire, a faculty of the University of Central England in Birmingham.

Vice-Principal: Professor Alastair Pearce,

Birmingham Conservatoire, Faculty of the University of Central England in Birmingham, Paradise Place, Birmingham B3 3HG

0121 331 5901/2

www:conservatoire.uce.ac.uk

The Birmingham School of Music has, since its inception, been Birmingham’s foremost institution devoted to applied music. For much of its history it has offered full-time courses for music teachers and performers as well as part-time courses in instrumental studies. The School also formerly offered instruction in speech training.

Former Principals of the School include the composer Dr Christopher Edmunds (1945-56), who was himself a native of Birmingham, and the baritone Gordon Clinton (1960-73), who held the post concurrently with a Professorship at the Royal College of Music. The violinist Louis Carus, who had been Head of Strings at the RSAMD, became Principal in 1973, and his successor in the new post of Director, Damian Cranmer (1983) was to go on to the position of Director of Music at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

In the 1960s the School achieved official recognition by the Ministry of Education as the West Midlands Regional College of Music for its diplomas in teacher training. In 1969 the BSM became part of the City of Birmingham Polytechnic. Upon the creation of the University of Central England in 1993, incorporating the former Polytechnic, the BSM enhanced its role and reputation by adopting the title of the Birmingham Conservatoire as a faculty of the UCE. There are now over 400 students, and courses are offered in jazz and music technology as well as the other musical disciplines. There is also a Junior School which provides instruction for students of school age.

The Conservatoire is fortunate in its premises, which include four organs and the Adrian Boult Hall, which seats 525. In 1994 a new extension was opened containing 40 teaching and practice rooms.

The Birmingham Conservatoire is now firmly established among the country’s music colleges and has strong links with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

The diplomas of the Birmingham Conservatoire use the normal robes of the University of Central England at Birmingham.

Academical Dress

Robes of the Birmingham School of Music

Gowns:

Oxford BA in black [b1]. For ABSM, there is a 2” V-shaped slit in the forearm seam.

Hoods:

ABSM: dark green, faced 3” yellow [f1].

LBSM: not known

FBSM and GBSM: dark green, lined yellow [f1].

Blessed Guild of St Cecilia

Early twentieth-century.

Academical Dress

Hood:

Purple lined claret, faced 2” gold on the turn-out [s7].

British Academy of Music

Date of foundation c.1989. Currently in abeyance.

The BAM was founded by David Wilde, who had been involved with the Curwen College of Music (q.v.) but had left after differences with Revd. Canon Dr Paul Faunch. Wilde became Secretary of the Academy, in which the late Barry St John Neville was also a prime agent.

The Patron was Sir Anthony Harris, Bart. Other Fellows of the Academy included Professors Gordon Phillips, Ian Tracey and Leonard Henderson, Della Jones, Dr David Bell, Dennis Puxty and Dr Maurice Merrell (q.v. under Guild of Musicians and Singers). There is currently only one FBAM hood in existence, owned by Dr Maurice Merrell. Due to conflict among its founders, the BAM was dissolved after a brief existence that consisted largely of planning meetings for its future activities. Despite some talk of its restarting under new management, it remains a dormant institution.

The BAM name is currently used by an unrelated body conferring awards on popular music artists.

Academical Dress

Hood:

FBAM: scarlet watered taffeta, lined old-gold satin [f1]. No gown was prescribed.

It is not known whether there were any other diploma awards; if there were, no Academical Dress was prescribed for them.

British College of Music

Date of foundation unknown, but was extant in the 1920s. Now presumably defunct.

Academical Dress

Gowns:

FBCM: black, with 3 red chevrons on each sleeve. – presumably [b1]

LBCM: black with 2 pink chevrons on each sleeve. – presumably [b1]

ABCM: black with 1 white chevron on each sleeve. – presumably [b1]

All wear a black square cap, with tassels:

FBCM: blue, orange, red,

LBCM: blue, orange, pink.

ABCM: blue, orange, white.

Hoods:

ABCM: dark blue, lined orange and bound 1” white [s1].

LBCM: dark blue, lined orange and bound 2” pink [s1].

FBCM: dark blue, lined orange and bound 3” red [s1].

Cambridge School of Music

Founded 1990; ceased operating in 1991.

The Cambridge School of Music was founded at Peterhouse, Cambridge, by the two Organ Scholars there, John Shooter and Lee Longden.

Honorary Fellows of the School included Professor Ian Tracey. Honorary Life Members included Revd. Norman Young, who served as Chaplain to the School.

Academical Dress

Gowns:

ACSM: Cambridge BA in black [b2].

LCSM: London MA in black, with 1” white facings [m5].

FCSM: Cambridge MA in black, with 4” white facings [m2].

HonCSM: Cambridge BA in black, with 1” white facings [b2].

DipMusCSM: Cambridge MA in black, with white facings and white ribbon over armhole* [m2].

DipMusTh: as for DipMusCSM, but with red ribbon over armhole*

*The ribbon was 2” wide, and ran the length of the armhole, similar to the Cambridge ScD undress gown.

Hoods:

ACSM: navy blue, bound 2” white on all edges [s1].

LCSM: navy blue, bound 1” white on all edges [f1].

FCSM: navy blue, lined and bound ¼” white [f1].

HonCSM: navy blue, lined white [a1].

DipMusCSM: navy blue, lined scarlet cloth, bound fur on the cowl only [f1].

DipMusTh: navy blue, lined scarlet cloth, bound fur on the cape only [f1].

The robes for other awards bestowed by the School (reported by Nicholas Groves to have included awards at the doctoral level) have not been ascertained. Awards of the Cambridge School of Music were transferred to those of the Cambridge Society of Musicians upon the demise of the School.

Cambridge Society of Musicians

Founded 1991

From 1995-2000 the CSM also maintained a teaching college known as Phillips College, presently suspended.

Chief Executive and Director: Lee Longden,

Music Management International Ltd, MMI House, 8 Quarry Street, Shawforth, Rossendale OL12 8HD

01706 853664

www:music-services.demon.co.uk (website was defunct as of July 2004)

The Cambridge Society of Musicians is a learned society of musicians and music educators, and restricts its membership to those who can prove an active involvement in the practice of music. Election to the various grades of membership is on the basis of the applicant’s prior qualifications and experience; for example, Fellowship is restricted to graduates in music or music education or those who can prove equivalent experience.

The Chief Executive of the CSM, Lee Longden (q.v. under Cambridge School of Music), is a former Organ Scholar of Peterhouse, Cambridge, and it is the Peterhouse colours of blue and white that may be found in the Society’s Academical Dress. Like the Deputy Chief Executive, Dr Ian Roche, he is a member of the teaching staff of the Faculty of Church Music of the Central School of Religion (q.v.). Dr David Bell (q.v. under Guild of Musicians and Singers) was Warden of the Society during the early 1990s.

CSM now has a large membership worldwide, and in countries where the size of the membership warrants it, National Directors may be appointed. A newsletter has been sent to members in the past and local social meetings are encouraged. The Society also announced some time ago that it plans to enhance its online facilities, which will include a discussion group and online archive of musical resources, and aims to make these its primary means of communication with the membership.

In 1995 CSM established Phillips College as its teaching branch, named after the late Gordon Phillips, HonFCSM, Professor of Organ and Harpsichord at the London College of Music (q.v.). During its period of operation Phillips College provided pilot schemes for accreditation of special needs music courses in schools and colleges and a scheme of school-based diploma and certificate awards for serving teachers. Since 2000, the College has been in the process of preparing its awards for accreditation by the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, and its activities have consequently been suspended.

In 2004 its website was removed, and the current status of the Society is not known.

From about 2000, CSM has additionally offered the rank of Companion, and the awards of Merit, Silver and Gold Medals for individuals who have made a substantive contribution to music.

Honorary Fellows of CSM include Wendy Eathorne, Lady Walton, George Melly, Sir David Lumsden, Professor Ian Parrott and David Flood.

Academical Dress

Robes of the Cambridge Society of Musicians

1. 2000-: certain specifications revised from rescension 2: other awards still use the robes in that rescension.

Gowns:

ACSM, AMCSM, MCSM: a black gown of Cambridge BA pattern [b2], with a blue cord and button on the yoke.

FCSM: a black gown of Cambridge MA pattern [m2], with a blue cord and button on the yoke.

HonAffFCSM: a black gown of Oxford MA pattern [m1], with a blue cord and button on the yoke.

HonCSM: a black gown of London MA pattern [m5], with a blue cord and button on the yoke.

HonFCSM: a black silk gown of Oxford MA pattern [m1], with a blue cord and button on the yoke; the upper edge of the sleeves and outer edges of the facings and yoke are trimmed with Cambridge doctors’ lace.

Companion: not known.

Hoods:

MCSM: black, lined blue, bound 2” inside and out with white [s2].

AMCSM: black, lined white, bound 2” inside and out with blue [s2].

AffFCSM: blue, lined and the cape bound white, the cowl bound 2” scarlet [f1].

HonFCSM: blue, lined scarlet, the cowl bound 1” white fur [f1].

2. 1991-2000

Gowns:

MCSM (discontinued before 2000): a gown similar to ACSM, but of undergraduate size.

ACSM: a BA pattern gown in black [b2], with the whole front sleeve seam split, and joined at the wrist by a blue button and loop. There is a blue cord and button on the yoke.

FCSM: a black stuff gown of the Cambridge doctors’ dress pattern [d1], with the facings covered and the sleeves lined with black; there are blue cords and buttons on the sleeves. There is doctors’ lace along the turned-back portion of the sleeve.

HonCSM: a black gown of London MA pattern [m5], with a 1” white ribbon along the outer edge of the facings.

HonFCSM: a black gown of Cambridge MA pattern [m2], with detachable white silk facings.

Hoods:

MCSM: (discontinued before 2000): black, faced 1” blue inside and out, and the cowl bound ½” white [s1].

ACSM: blue, lined self-colour, bound 2” white on the cowl, and with a light blue ribbon, ½” wide set ½” away [s2].

FCSM: blue, lined and the cape bound ½” white [f1].

HonCSM: blue, lined white [a1].

HonFCSM: as FCSM, but the cape bound ½” scarlet.

Note 1: Councillors have special robes: the gown is as for FCSM, but the facings and sleeve-linings are blue; the hood is blue, lined scarlet (cloth originally, subsequently silk), the cowl faced 1” white watered silk (fur originally, until 1995) [f1].

Note 2: Originally, teachers who held a diploma of the CSM were permitted to bind their hoods with ½” gold.

3. American hood scheme for certain awards, applicable to members residing in the USA only

MCSM: American Intercollegiate Code Bachelors’ shape, black, lined blue with a white chevron and music faculty (pink) binding.

AMCSM: AIC Bachelors’ shape, black, lined blue with a gold chevron and music faculty binding.

ACSM: AIC Bachelors’ shape, blue, lined white with a black chevron and music faculty binding.

FCSM: AIC Doctors’ shape [f14], blue, lined white with a scarlet chevron and music faculty binding.

HonCSM: AIC Bachelors’ shape, blue, lined white with a scarlet chevron and music faculty binding.

AffFCSM: AIC Doctors’ shape [f14], blue, lined white with one gold and one scarlet chevron and music faculty binding.

HonFCSM: AIC Doctors’ shape [f14], black, lined gold, with two scarlet chevrons and music faculty binding. The gown is of AIC Doctors’ pattern, in black, with three black chevrons on the sleeves piped in scarlet.

Robes of Phillips College

Graduates of the College, whatever their diploma, wear a black gown of Oxford BA pattern [b1] with a purple cord and button on the yoke, and a black hood, lined purple with a 3” gold chevron [s1].

Honorary Fellows (FPC) wear an Oxford MA gown in black [m1], with three purple buttons set horizontally over the armhole, and joined by a purple cord; there is a gold cord and button on the yoke. The hood is of Durham doctors’ pattern [f4], in purple silk, lined cream brocade, bound on all edges with gold cord.

Staff Members wear a special hood: scarlet stuff, lined purple, bound on all edges with 1/8” gold cord. [f4]

There are no special robes as yet for Honorary Members and Associates.

Central Academy of Music[i]

Founded 1985

Principal and Director of Examinations: Dr Donald Heath

Empire House, 175, Piccadilly, London W1J 9TB

www:centralacademy.org

The Central Academy of Music was founded as an examining board by Dr Donald Heath and the late Ray Turnecliffe in order to encourage the playing of the electronic keyboard. Its Director of Administration is Stephen Rhodes. It offered Grades 1 to 9 initially, and later on diplomas were introduced. At that time no other college offered examinations in electronic keyboard[ii]. Today the Academy also offers examinations in piano and electronic organ, and has centres throughout the UK and Ireland leading to a busy programme of examining throughout the year.

CAM syllabuses are wide-ranging and flexible, and the Academy’s friendly but rigorous approach has won a loyal following in the popular organ world and beyond.

CAM is a company limited by guarantee in the United Kingdom.

Academical Dress

Gown:

Oxford MA in black [m1]. For FCAM, the facings are purple.

Hoods:

ACAM, AMusCAM: dark green, lined light green faced 2½” rose [f1].

LCAM, LMusCAM: dark green, lined rose faced 2½” gold [f1].

FCAM: gold slipper satin, lined purple bound 1” white fur [f1].

HonCAM: white, lined purple faced 2½” gold [f1].

Church Choral Society and College of Church Music; see Trinity College of Music

Church Organists’ Society

(sometimes called the Guild of St Cecilia, later appears to have been known as the Society of Church Organists)

Date of foundation unknown, but active in the early twentieth-century. Now defunct.

Academical Dress

Hood:

FCOS: black silk, lined white silk bound 1½” red silk [s1]. This diploma had been renamed FSCO by 1927.

College of Church Musicians

Early twentieth-century. Described as affiliated to the Guild of Church Musicians in Northam’s MS copybook. Likely the British branch of the Kansas, USA, institution described below.

Academical Dress

Northam[iii] gives the following hood:

FCCM: dark slate blue lined and bound light blue. [?]

The Ede and Ravenscroft Chancery Lane “bible” gives the following hoods:

ACCM: black lined and edged blue, the cowl bound fur.

Master: blue ‘tabby[iv]’ lined and bound London Laws blue.

Doctor: blue ‘tabby’, lined and bound London Science gold.

College of Liturgical Arts

Founded 2003.

www:sfrc.org

The College of Liturgical Arts was founded by Revd Stephen Callander and others as an examining body in theology and liturgical arts and related areas. It appoints to named fellowships, among which appointees are Aaron Kiely, Philip Allison, Peter Halliday and Revd. Andrew Linley. Its Faculty of Musicians in Worship was a dependent body functioning as a learned society that elected members without examination, now (2004) ceased.

Academical Dress[v]

Gowns:

FCLA jure dignitatis: black with facings and 4” sleeve trim of red purple St Aidan brocade [d2].

FCLA: black with facings of red purple St Aidan brocade [d2].

FFMW: none specified.

LCLA, ACLA, DipLitArts, CertLitArts, DipTheol, CertTheol: Oxford MA in black [m1].

Hoods:

FCLA jure dignitatis: black lined red purple St Aidan brocade [f5].

FCLA: black lined red purple St Aidan brocade [f5] with the inside of the cowl only edged 3″ of taffeta in the relevant discipline colour.

FFMW: black art silk, lined pale blue taffeta, and faced inside with 2″ red-purple St Aidan brocade [f5].

LCLA: black lined red purple St Aidan brocade [s2] with the inside of the cowl only edged 3″ of taffeta in the relevant discipline colour.

ACLA: black with the inside of the cowl only edged 1″ of taffeta in the relevant discipline colour and 4” red purple St Aidan brocade set next to the taffeta [s2]

DipLitArts, DipTheol: black cotton viscose, fully lined red purple St. Aidan brocade. The inside of the cowl is edged 2” white fur [a1].

CertLitArts, CertTheol: black cotton viscose, fully lined red purple St. Aidan brocade [a1].

Discipline colours:

Music: gold

Theology: purple

Practical liturgy: red

Vesture: green

Liturgical design: black

Faculty members wear an amaranth red cincture with fringed fall.

College of Music and Drama, Cardiff; see Welsh College of Music and Drama

College of St Nicolas; see Royal School of Church Music

College of Violinists; see Victoria College of Music

Correspondence College of Church Music

Founded as the Williams School of Church Music in 1971.

The WSCM closed c.1985 but the Williams charity is still extant (see below). The CCCM was established c.1985, and closed c.1990.

The Williams School of Church Music was founded with a bequest from G.H.T. Williams, a wealthy Methodist amateur organist. He built a substantial extension to his house at 20, Salisbury Avenue, Harpenden, in order to house an organ that he had acquired from his former church in East London. This concert hall could accommodate about 150 people, but was seldom used in Mr Williams’ lifetime. Teaching took place there from around 1961 onwards. After his death his home became the Williams School of Church Music, with Dr Francis Westbrook (1903-75), also a Methodist and professor of counterpoint at the London College of Music (1968-75), as its first Principal. The School was a registered charity governed by a Trust Deed of 20 March 1970.

The School remained relatively inactive until Clive Bright was appointed Principal in 1976, following the death of Dr Westbrook. Clive Bright was a London-based consort conductor who was resident in Harpenden. Under his leadership musical activities of all kinds expanded hugely, and the WSCM went from having no pupils to some 600, ranging in age from 5 to 72. In addition to individual instrumental tuition leading to a variety of examinations, there were brass groups, choirs, string and wind bands. There was also a chapel choir which sang Choral Evensong every Wednesday during term-time and on some Sunday evenings as well.

Clive Bright was the driving force behind all this activity, and the School closed down some eighteen months after his departure in 1984, by which time the School was suffering from financial problems. Unfortunately little was done by the Williams trustees to support the School or perpetuate the wishes of its founder. The concert hall was demolished in 2001, and its site is now being re-developed for housing. Parts of the organ were used in the re-building of the organ at High Street Methodist Church, Harpenden.

The Correspondence College of Church Music was established after the WSCM had closed in order to allow WSCM distance learning students to finish their courses, also offering some new distance learning courses. It was an extremely small-scale enterprise of far less significance than the WSCM had been, administered by Clive Bright and the former Registrar of the WSCM, Barbara Fairs, with support from Dr John Winter and Dr Frances Knight. All staff worked on a voluntary basis. Its activities ceased around 1990.

In recent years the Williams School of Church Music has resumed some activity in the guise of the Williams Church Music Trust, which continues the original registered charity. This is a grant-making body concentrated upon music within the Church of England. In 2005 its trustees were listed as sponsor for, among others, the St Albans Choral Society and Bach Choir, a recital at Lichfield Cathedral and the top prize at the St Albans International Organ Festival (£5,500).

Note: The author is indebted to Dr Frances Knight for the main body of this article.

Academical Dress

Hoods of the Correspondence College of Church Music

DipCCCM: black, faced 3” purple, the cowl bound 1½” gold, the gold edging folded to shew ¾” either side [f1][vi].

ACCCM: black, lined purple, bound 1½” gold on all edges, the gold edging laid flat inside the cowl and outside the cape so as to shew 1½” when worn [f1].

Hoods of the Williams School of Church Music

LWSCM: black, faced 3” violet, edged gold [f3].

FWSCM: black, lined violet, edged gold [f3].

Note 1: HonWSCM had no robes.

Note 2: There were no prescribed gowns.

The Curwen College of Music

Founded 1863 as the Tonic Sol-Fa College of Music.

Re-named the Curwen Memorial College in 1944, but also continued to use the original name.

Re-organised as the Curwen College of Music in 1972.

Warden: Dr Terry Worroll

259, Monega Rd, Manor Park, London E12 6TU

http://mysite.wanadoo-members.co.uk/Curwen

The Tonic Sol-Fa College of Music was founded by the Revd. John Curwen (1816-80) at Forest Gate, east London, in 1863. The instrument of government was drawn up in 1869 and incorporation followed in 1875. Curwen had taught himself to read music from a book by the originator of tonic sol-fa, Sarah Glover. He was responsible for developing and integrating the tonic sol-fa method into a comprehensive educational vision for all classes and ages of people that, in his plans for the College, would embrace the training of teachers, the education of students and the provision of a rigorous series of examinations using tonic sol-fa extending from the first grades up to Fellowship. From the outset, the College has always taken a strong interest in choral music. The activities of Curwen’s college were complimented by those of his publishing house, J. Curwen and Sons, which continued as a publisher of educational music until the 1970s.

It was found that the original premises were too far from the centre of London to carry out the College’s mission effectively and therefore new premises were sought. In the early years of the twentieth-century the College was to be found at 27, Finsbury Square, London EC1. From 1939-44 it was housed in Great Ormond Street and in 1944 moved to more spacious accommodation at Queensborough Terrace. During this period, the College was afforded continuity by its long-serving Secretary, Frederick Green, who had been involved with the College from its early years. At one point those wishing to submit for diplomas had first to become shareholders of the College.

In 1967 a decisive development in the College’s history was marked by the appointment of the Revd. Canon Dr. Paul Faunch as Principal of the TSC and Chairman of the separate Curwen International Music Association (a fellowship with especial interest in choral music for past and present students of the College, under the patronage of Dr Zoltan Kodaly). In 1972, he presided over a major re-organisation of the College which saw it re-named and renewed in its pursuit of Curwen’s method.

This period saw the College once again housed in the London suburbs, it having moved to Bromley. Previously, in the 1960s, largely due to the energetic influence of the late Dr Rupert Judge (d.1986), the Curwen College had became affiliated to the Geneva Theological College (q.v.), which affiliation continued until the Geneva Theological College became a part of Greenwich University, Hawaii (now Norfolk Island), in 1990. At this time the College’s activities were diverse, so that it offered not only tuition for its own examinations (which were also available to external candidates), but also preparation for GCE Music and other public examinations. Further training for qualified teachers was offered by means of the School Teachers’ Music Certificate, which offered an introduction for those who wished to teach class singing. There were then twelve different pathways to the College’s diplomas.

Concurrently with the 1972 re-organisation a number of members of the College broke away to form a new Curwen Institute (under the leadership of the educationalist Bernarr Rainbow) which has since concentrated its work on the applicability of the Curwen method to primary education. It has awarded a diploma in tonic sol-fa teaching (presently suspended) as listed below.

Dr Faunch continued at the helm of the College until his death in 1997. In the succeeding period, under the guidance of Dr Terry Worroll, the present Warden, the College has been the subject of an ongoing revision, reflecting its contemporary nature as an examining body rather than a teaching institute.

Academical Dress

Current robes (1997-)

Gowns:

AMusCCM: London BA in black [b4] ([b1] until 2003).

LCCM: London BA in black [b4].

FCCM, HonCCM and HonFCCM: CNAA MA in black [m10].

Hoods:

AMusCCM: light blue, faced 2” crushed strawberry, the cowl bound ½” old gold [s1 until 2002; s2 since 2002].

LCCM: light blue, faced 4” crushed strawberry, the cowl bound ½” old gold [f1].

FCCM: light blue, lined crushed strawberry, bound 1” old gold on all edges [f1].

HonCCM: light blue, lined old gold, faced 4” crushed strawberry [f1].

HonFCCM: light blue, lined old gold, bound 1” crushed strawberry on all edges [f1] (now obsolete).

Note: in 2002, the award of HonFCCM was withdrawn; now all new Fellows, whether admitted ordinarily or honoris causa, wear the FCCM robes.

Previous robes (1972-97)

Gowns:

ACCM and HonCCM: a black gown with bell-sleeves [d2].

LCCM: London BA in black [b4], with brown cords and buttons on the sleeves and yoke.

FCCM: Oxford lay gown in black [d4], with brown watered facings.

Hoods:

ACCM: brown watered taffeta, lined dark brown [s1].

LCCM: brown watered taffeta, faced 3” old gold*

FCCM: brown watered taffeta, lined old gold*.

HonCCM: brown watered taffeta, lined dark brown, bound ½” old gold on all edges.*

*These were made in the Warham Guild shape until 1997, when they were changed to [f1].

Robes of the Tonic Sol-Fa College (18—1972)

Gowns:

FTSC: a black gown of Oxford BA pattern [b1], with three black cords and buttons on each sleeve.

Others: a black gown with bell sleeves [d1].

Hoods:

ATSC/AMusTSC: no hood.

LTSC/LMusTSC: light blue, bound 2½” dark pink on all edges [f1].

FTSC: light blue, lined dark pink [f1].

HonTSC: light blue, bound ½” dark pink, and faced 1” dark blue velvet [f1].

DipMusEdTSC: light blue, lined slate blue[vii], faced outside 1” dark pink and 1” slate blue [f1].

Original robes (1863-18–) (as given in Haycraft)

Hood:

FTSC: ruby poplin, bordered white fur [s1].

Northam gives:

FTSC: puce silk edged fur. [?]

The Ede and Ravenscroft Chancery Lane “bible” gives:

Gowns:

ATSC: black, with blue cord and button on yoke.[b1 or d4?]

LTSC: black, with blue cord and button on sleeves [b4]

FTSC: was as given above, but then as London MA, but with an upright cut to the armhole, extending to the sleeve head, and a black cord and button on the yoke.

Hoods:

ATSC: none.

LTSC: blue, bound 3” Sheffield Arts pink.

DipMusEd: lined Wales Divinity silk.

Revd. Philip Goff’s small MS book gives:

Hoods:

LTSC: London music blue bound 3” Cambridge Laws pink inside [s1]. Altered in 1937 to London music blue, bound 3” in and out on all edges Sheffield arts pink (crushed strawberry). [f1].

FTSC: London music blue lined Cambridge Laws pink [f1]. Altered in 1937 to London music blue lined Sheffield arts pink (crushed strawberry). [f1]; the neckband is pink.

Robes of the Curwen Institute (1973-?)

Hood:

Diploma in Tonic Sol-Fa: black, lined pink and edged with blue silk [s1].

Derby Institute of Music

A diploma of this institution is in the possession of Dr Terry Worroll. He writes:

“Its President was The Most Hon. The Marquess of Hartington. The diploma I have was awarded to Francis Cotter Lapthorne (he was known as Frank) in November 1950. The diploma (Associate) was awarded honoris causa! The designatory letters were AIMD.

The names of the ‘Founder Patrons’ are given at the top of the certificate which is printed on very good watermarked paper. The watermark has a crown in it (possibly the Marquess’s very own paper?) but it is upside-down or, rather, it has been printed upside-down.”

If academic dress was used, it is not known.

Examining Board for Music

Founded 1996. Now defunct.

The Examining Board for Music was founded by Paul Carter and Lee Longden (q.v. under Cambridge School of Music) as an attempted breakaway movement from another institution with which Paul Carter had been involved. As far as can be ascertained, few if any diplomas were awarded and the Board never commenced serious activity. It became defunct within a short time of its inception.

Academical Dress

Gown:

a black gown of Dublin MA pattern [m3]. Honorary fellows wear a gown of American Intercollegiate Code doctors’ pattern in cherry, with black velvet sleeve-bars and facings.

Hoods:

AEBM: black, faced 2” gold [s1].

LEBM: black, lined gold [s1].

FEBM: black, lined gold faced 2” cherry [s1].

HonFEBM: black, lined cherry faced 2” gold [s1].

Faculty of Church Music

Founded 1956; since post-1968 part of the Central School of Religion (q.v.)

In 1980 it incorporated the Society of Church Musicians, founded c.1970.

Registrar and Treasurer of the CSR: Revd. Geoffrey Gleed,

27, Sutton Park, Blunsdon, Swindon, Wiltshire SN2 4BB

What is now the Faculty of Church Music of the Central School of Religion was originally formed as a diploma-awarding body called the Faculty of Church Music in order to provide the Free Churches with an alternative to the Guild of Church Musicians (q.v.). The first President (from 1957) was the Rt. Revd. G.F.B. Morris, who was a Bishop of the Church of England in South Africa and a leading evangelical. The Acting Chairman in 1958 was Alfred H.C. Stevens and the Council included Dr C. Bendall, C.M. Hansen and Dr F.R. Thornton. The founding Honorary Secretary and Executive Officer was Dr Douglas Geary, who in 1967 became President of the Central School of Religion (q.v.) A few years after this the FCM was absorbed into the CSR, where its diploma programmes continue alongside the degrees in Church Music that were introduced in 1980. The current Director of the FCM, Dr Andrew Padmore, was formerly Organist of Belfast Cathedral.

Former Presidents of the FCM include Revd. Dr John Styles, formerly Precentor of St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh and also sometime Principal of Victoria College of Music (q.v.) and Revd. Canon Dr Paul Faunch, who was also Warden of the Curwen College of Music (q.v.)

The awards of the original grades of Associate and Fellow were made after examination; this was changed in 1958 to a system of accreditation of prior learning and experience and this method of award has continued ever since, supplemented by teaching and coursework. The award systems were revised in about 1997. A scheme of examinations for lay readers and their counterparts in the Free Churches has also been operated, leading to the former Bronze and current Silver and Gold Medals of the FCM in the Spoken Word and to the AFCM and LFCM in the same discipline.

The Society of Church Musicians was formed along similar lines to the FCM circa 1970 and merged with the FCM in 1980. This merger saw the FCM introduce a greater level of support and teaching in theoretical aspects of church music.

Honorary Fellows of the FCM have included Rodney Baldwyn, Richard Fenwick, Colin Mawby, Lt-Col. Dr Ray Steadman-Allen (q.v. under National College of Music and London Society for Musicological Research), John Ewington (q.v. under Guild of Church Musicians) and Professor Ian Tracey. The award of Life Member was previously made in recognition of meritorious service; it has not been awarded in recent years.

Academical Dress

Robes of the Faculty of Church Music

Gowns:

1958-

a black gown with bell-sleeves [d2], faced navy blue.

1956-58

AFCM: black stuff, with the sleeves looped by a twisted purple cord and button, and a twisted purple cord and button on the yoke [b4?].

FFCM: black stuff, with the sleeves looped by a twisted purple cord and button, and a pink cord and button on the yoke [b4?]

Hoods:

1999-

AFCM: navy blue silk, faced 3” black velvet [f3].

LFCM: navy blue silk, lined black velvet [f3].

FFCM: black velvet, lined navy blue silk [f3].

1980-99

AFCM: navy blue, lined self-colour [s1].

LFCM (introduced post-1980): navy blue, faced 3” black velvet [s1].

FFCM: black velvet, lined navy blue [s2].

1958-80

AFCM: pink rayon, lined purple [f1].

FFCM: pink rayon, lined purple, the cowl bound 1” fur [f1].

1956-58

AFCM: black stuff, lined purple, the cowl bound 1½” pink rayon [shape unknown]

FFCM: pink rayon, lined purple [shape unknown].

Note 1: in 1980 the original hoods for AFCM and FFCM were transferred to become the hoods for MMus and BMus of the Central School of Religion (q.v.) and the FCM adopted the hoods of the SCM (see below).

Note 2: post-1980, holders of the ChM diploma were entitled to bind the cowl of the hood with 1” fur; life members with 2” old gold. This no longer applies.

Note 3: Canon Dr Paul Faunch had an FFCM hood in black velvet lined cherry [s2]. This may have been a prototype, or the cherry may have faded from navy.

Robes of the Society of Church Musicians

MSCM: as for AFCM (1980-99).

FSCM: as for FFCM (1980-99).

Faculty of Church Organists

Founded 1989. Currently dormant.

The Faculty of Church Organists was founded by Dennis Puxty (q.v. under Guild of Musicians and Singers). Originally it was limited to four Fellows: Puxty, Nicholas Groves (q.v. under Norwich School of Church Music), Lee Longden (q.v. under Cambridge Society of Musicians) and Dr Maurice Merrell, with a fifth Fellow later added in the person of Professor Ian Tracey. Dennis Puxty acted as Presiding Fellow until his death, when this position was taken over by Professor Ian Tracey. The Faculty is not active at present.

Academical Dress

Gowns:

MFCO: a black gown of Cambridge BA pattern [b2] (not awarded).

FFCO: a black gown of Cambridge MA pattern [m2].

Hoods:

MFCO: black, lined black watered, the cowl bound 2” lilac [s1].

FFCO: lilac, lined black watered, the cowl faced ½” old gold [s2]. Originally this hood had no gold facing and was made in the Glasgow shape [f9].

Faculty of Liturgical Musicians

Founded 2001.

Assistant Director: Revd. Andrew Linley,

37, Acacia Road, Enfield, Middlesex EN2 0LY

http://mysite.wanadoo-members.co.uk/facultylm

Originally founded as a subsidiary society of the Central Institute London[viii], the FLM has been independently administered since 2003. Fellowship of the FLM was originally open only to existing members of the CIL who held a musical qualification; now the CIL restriction has been lifted and all who are musically qualified may apply. Associateship is open to all who support the aims of the Faculty. There are no fees payable for membership. The FLM exists to promote liturgical music and support those involved in its practise.

The Director of the FLM, Stephen Crosbie, is organist and choirmaster of Kirkcudbright Parish Church, Dumfries.

Academical Dress

Hoods:

FFLM: dark red cotton viscose, the cowl faced 3” red shot green silk, the neckband lined and bound 3/8” red shot green silk top and bottom [f3].

AFLM: dark red cotton viscose, faced red shot green silk [s1].

Forest Gate College of Music; see Incorporated London Academy of Music

Glasgow Athenæum School of Music; see Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama

Guild of Church Musicians

Founded 1888 as the Church Choir Guild

Known as the Incorporated Guild of Church Musicians from 1905.

Now known by its present title.

General Secretary: John Ewington, OBE,

St Katharine Cree, 86 Leadenhall Street, London EC3A 3DH

01883 741 854

www:churchmusicians.org

The Guild of Church Musicians was founded as the Church Choir Guild under the patronage of the Archbishop of Canterbury (Dr Frederick Temple) and Sir George Elvey (Organist of St George’s Chapel, Windsor). It exists to promote Church Music in all its forms and to raise the technical and general proficiency of those who practise it.

Formerly, the Guild offered examinations leading to the award of its diplomas as an incorporated institution. Now it administers the awards of the Preliminary Certificate (designed for younger musicians), the Archbishops’ Award (introduced 1994), which examines by tests of practical musicianship, portfolio submission and viva voce, and the more searching Archbishops’ Certificate, (administered by the Guild since 1961), which consists of the requirements for the Award plus two prepared essays and a written examination in worship and church music. The award of FGCM is a higher award available through distance learning. Holders of the Preliminary Certificate and Archbishops’ Award may wear a badge suspended from a ribbon of the Guild’s colours. The Guild’s examinations are open only to its members.

To aid those preparing for its awards the Guild runs courses and publishes works of guidance. One such is the recent “Landmarks in the development of Christian Worship and Church Music” by John Ewington, OBE, and Revd. Canon Arthur Dobb, which is of particular help to ACertCM candidates.

Membership of the GCM was originally open to members of any church in communion with Canterbury; since 1988 it has been open to all Christians. There is currently a substantial membership overseas. In the centenary year of 1988 the then Archbishop of Canterbury invited the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster to become joint patron of the Guild. The Archbishop of Canterbury is now no longer patron.

The Guild’s magazine, “Laudate”, is sent to members three times a year, together with the annual Year Book.

The President of the Guild is Dr Mary Archer and the Warden is the Dean of Monmouth.

Academical Dress

Fellowship (FGCM):

Hood:

royal blue, lined self-colour, faced 3” terra-cotta [f1][ix]. There is no gown specified.

Associateship (AGCM)[x]

not known.

The Guild administers the Archbishops’ Certificate in Church Music (ACertCM), for which the hood is black lined black stuff, the cowl faced 1” spectrum blue, bound terra-cotta cord on all edges [was [s2] modified; now [f1]]. There is no special gown. The recently-introduced Archbishops’ Certificate in Public Worship (ACertPW) is also administered by the Guild; its hood is black lined black stuff, the cowl faced 1” terra-cotta, bound spectrum blue cord on all edges [was [s2] modified; now [f1]].

See under Royal School of Church Music for the Archbishop’s Diploma in Church Music (ADCM, formerly ACDCM).

The diplomas of the Incorporated Guild were as follows:

Gown:

Oxford BA pattern in black [b1], with terra-cotta velvet stripes placed horizontally on the sleeves, 6” x 1”; 2 for AIGCM, 3 for LIGCM and 4 for FIGCM.

Hoods:

AIGCM: black, bound ½” terra-cotta on all edges [f1].

LIGCM: as AIGCM, with a extra band of terra-cotta, 1” wide, set inside the cowl 1” away form the binding [f1].

FIGCM: royal blue, lined self-colour, bound ½” terra-cotta on all edges [f1].

Previous hoods (these had changed by 1947):

AIGCM: black corded, faced old gold, the neckband edged crimson silk [s1].

LIGCM: black, lined old gold [s1].

FIGCM: crimson, lined gold shot silk, the neckband edged ¼” gold shot silk [s1].

HonFIGCM, also Fellows by examination who were Life Members: as for FIGCM, but also bound fur [s1].

Original robes (1888-18–)

Hood:

FCCG: crimson silk, bound fur [s1].

There were no robes for other awards.

Robes as given in Northam

Guild of Church Musicians

Gowns:

FGCM (Hon & council): black, with three strips of black velvet, 6” x 1”, with pointed ends. [b1]

FGCM(ChM): black, with three strips of black velvet, 6” x 1”, with pointed ends. [b1]

FGCM(Org): black, with three strips of black velvet, 6” x 1”, with pointed ends. [b1]

Hoods:

FGCM (Hon & council): crimson corded silk, lined shot gold silk, edged fur.

FGCM(ChM): crimson corded silk, edged fur

FGCM(Org): crimson corded silk, the neckband bound ½” shot gold silk, edged fur

Church Choir Guild

Robes as for GCM above, but designated FCCG. There was a black square cap with crimson tassel. ACCG: a gown as for FCCG/FGCM, but with two strips of velvet. A cap with black tassel; no hood.

Later in the book is another entry for the FCCG, where the hood is described as being lined with London Science shot gold. The hood shape is a special simple, like Wales [s5], but with the liripipe removed.

Also on the same page is an entry for the GCM:

FGCM: London music blue[xi], lined London science gold [f5].

AGCM: black, lined Dublin MA blue, bound all edges 1” in and out with fur. [s1 or 2].

Guild of Concert Performers

Founded by James Holt (q.v. under North and Midlands School of Music) in about 1999.

Academical Dress

FGCP: not known.

The Guild of Musicians and Singers

Founded 1993

Master: Dr David Bell

8, Clave Street, London E1W 3XQ

020 7488 3650

www:musiciansandsingers.org.uk

It was with an awareness of the traditional role of guilds and fraternities in the lives of professional musicians that the late Dennis Puxty founded the Guild of Musicians and Singers. Dennis Puxty was both an accountant and an organist, and he established as a guiding principle of the Guild that it should draw its membership equally from professional and amateur musicians, allowing through its meetings the productive discourse that characterizes a learned society. Other leading members have included Dr David Bell, late organist to Herbert von Karajan, and Dr Maurice Merrell, chairman of the organ builders Bishop and Son.

The twice-yearly meetings of the Guild take place in central London and are committed to celebrating a high standard of musical performance throughout. To that end, recent programmes have included recitals on both the church and theatre organs, a piano recital of Chopin and concerts by chamber and brass ensembles. Illustrated lectures and talks are also an important feature of the Guild’s activities.

The Guild’s newsletter is lively in style, including both articles on performance-related subjects and reviews of live and recorded music.

The membership now stands at around 300 and includes a number of distinguished musicians. Candidates are elected to one of three levels of membership. As well as its distinctive Academical Dress, the Guild has its own tie.

Academical Dress

Gown:

a black gown of London BA pattern [b4], with crimson facings and purple cords and buttons on the sleeves.

Hoods:

AGMS: crimson, lined purple [s1].

LGMS: crimson, lined purple [f1].

FGMS: crimson, lined and the cape bound 1” purple [f1].

Note: founding fellows wear the FGMS hood with 1” fur on all edges; councillors with 1” fur on the cowl.

Guild of Organists

Date of foundation unknown, but active in the late nineteenth-century. Now defunct.

The Guild was confined exclusively to the Episcopal Church of England and those churches in communion with it.

Academical Dress

Hood:

FGldO: black poplin, lined crimson satin, faced 6” fur [s1].

Northam gives the following:

FGldO: black lined rose pink edged fur.

The Guildhall School of Music and Drama

Founded 1880 as the Guildhall School of Music

Known by present title since about 1935.

Principal: Professor Barry Ife

Silk Street, Barbican, London EC2Y 8DT

020 7628 2571

www:gsmd.ac.uk

The Guildhall School of Music and Drama evolved from the Guildhall Orchestral Society and was founded by the Corporation of the City of London. The Corporation’s Music Committee has controlled the affairs of the School since its foundation.

Having initially been accommodated in a disused warehouse in the City of London, in 1886 the School moved to premises on the Thames Embankment, with a further extension to these premises reflecting an expansion in student numbers following in 1889. Throughout the early life of the School part-time students only were accommodated in the School’s programmes of study. In 1920 full-time courses were introduced by public demand, with drama now occupying a substantial part of the School’s activities. The School has since 1977 been accommodated in large purpose-built premises in the Barbican Centre, a striking concrete listed building in the heart of the City.

In addition to the performers’ course, the School formerly offered a three-year course of graduate status leading to the diploma of GGSM intended for school teachers. Since 1991 it has offered degree courses validated by the University of Surrey and City University, including a DMA course which is jointly taught by the two institutions. The Concert Recital Diploma is reserved for elite postgraduate students and is the equivalent of the European premier prix. The School has also established a reputation as a centre for training in Music Therapy at postgraduate level. The student body is substantial and international in nature; the School has earned a reputation for being both informal and innovative.

The School also operates its own long-standing system of local graded music examinations and external diplomas.

The professorial staff has included a number of distinguished musicians of international standing, amongst which may be counted the violinists Yfrah Neaman and David Takeno and the clarinettist Jack Brymer. Past students of the GSMD can be found in all the major orchestras and many have also pursued successful careers as soloists and in music education. Jazz is now a significant part of the School’s activities.

The office of Principal has been filled by a number of distinguished musicians and musical administrators, including Joseph Barnby, Allen Percival and Sir John Hosier.

Academical Dress

Gowns:

LGSM: a black gown of Oxford BA pattern [b1].

AGSM: as GGSM, but without the braid.

GGSM: a black gown of Oxford BA pattern [b1] with 3 bars of black braid in each sleeve, 4½” wide, set 2” apart. There is a red and white flash on each facing.

FGSM: a black gown of the Oxford MA pattern [m1], with 3 vertical cords and buttons from the armhole to the shoulder, 1 red between 2 white.

HonGSM: no robes.

Hoods:

LGSM: black, lined white, with a red chevron [s1].

AGSM: black, lined red, with a white chevron [s1].

GGSM: black, lined red, with a white chevron [f1].

FGSM: black, lined and bound red, with three chevrons, white, blue, white, each 1” wide on the lining [f1].

Note: previously only those holding Teachers’ diplomas were permitted to wear Academical Dress; those with Performers’ diplomas wore no robes. In 1970, the GGSM diploma was the only one to use robes.

Hampstead Academy; see Incorporated London Academy of Music

Huntingdonshire Regional College, School of Music

Awards ceased at some point after 1988.

The Director of Music, Dr Roger Tivey, made a very small number of awards to colleagues and close friends.

Gowns:

HonDMus: light violet watered silk, the facings and sleeves covered with magenta[xii]. [d2]

Honorary Fellowship: none specified.

Hoods:

HonDMus: light violet watered silk, lined and bound ¼” magenta. [f1]

Honorary Fellowship: mid-green panama, lined white silk. [a1]

Imperial Conservatoire of Music

Early twentieth-century.

Academical Dress

Gown:

FICM: black, with gold cord and green button on each sleeve. [b4]

Hood:

FICM: green, lined old gold watered. [s1]

Incorporated Association of Organists

Founded 1913 as the National Union of Organists.

Known by present title since 1929.

Hon. General Secretary: Richard Popple,

11, Stonehill Drive, Bromyard, Herefordshire HR7 4XB

01885 483 155

www:allegro.co.uk/iao

This hood is unofficial, and is believed to have been designed by a member of the IAO. Both it and the use of the letters MIAO to signify membership have never been sanctioned in any way by the Incorporated Association of Organists. For this reason the history of the IAO is not included here.

Academical Dress

Hood:

MIAO: light green, part lined and bound fur [s1].

Incorporated Guild of Church Musicians; see Guild of Church Musicians

Incorporated London Academy of Music

Founded 1861.

In 1904 it incorporated the London Music School, founded 1865, the Forest Gate College of Music, founded 1885, and the Metropolitan College of Music, founded 1889. In 1905 it incorporated the Hampstead Academy.

Since 1935 known as the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art.

www:lamda.org.uk

The Incorporated London Academy was founded by Henry Wylde and soon established a high reputation as a centre for general musical training. Having incorporated a number of smaller institutions in 1904-05, the Academy gained a new principal in Dr Thomas Henry Yorke Trotter, who was instrumental in developing new approaches to music education for children. The Academy was at this time based at St George’s Hall, Langham Place, London W1.

In 1935, by which time the Academy was under the direction of Wilfrid Foulis, its name was changed to reflect the importance of dramatic training in its mission; speech and drama had in fact been taught since the Academy’s early years. The outbreak of war in 1939 saw the Academy close and move from London for the duration of the hostilities. When it re-opened in 1945 it abandoned musical training altogether and began to operate purely as a drama school, and thus it continues up to this day. Since its re-opening, the College has awarded additional diplomas to the one listed below; these are omitted from the listings because they are awarded purely in speech and drama and do not use Academical Dress.

Academical Dress

Hood:

ALAM: black, lined blue [s1]. This hood is no longer used.

ICMA (Independent Contemporary Music Awards)

Founded 1984-5

Registrar: Margaret Woolway, PO Box 134, Witney, Oxon. OX29 7FS

07000 780728/08704 599698

www:icma-exams.co.uk

It may justly be said that ICMA was one of the first examining bodies to take seriously the concept of examinations combining both serious and popular music, through the grades to diploma level, a concept that has since been widely adopted by the “traditional” institutions. They were the first to offer an options list of supporting tests for practical examinations, and candidates are able to offer alternative pieces for approval to play at the examination.

ICMA is notable for its highly flexible approach to examining, arranging times at the candidate’s convenience and conducting the examination in surroundings familiar to the candidate. It has a substantial and loyal following throughout the UK.

In addition to its principal work of examining, ICMA offers an advice line, a regular newsletter and endeavours to organise both formal and informal social events for students and teachers.

As well as their main office in Witney, ICMA also maintains a base in Scotland.

Academical Dress

There have been four rescensions, as follows:

2002-

All awards unchanged from the 1998 rescension, except:

FDipMusP/T was replaced by AdvDipMusP/T – with no change in the prescribed robes.

Gowns:

HonPDMusEd, PPICMA (which replaced the former PDMusEd): Cambridge MA in black stuff [m2].

All other honorary awards except HonFMusICMA (which is unchanged): Cambridge BA in black stuff [b2].

Hoods:

PPICMA: grey watered silk, lined red watered silk, faced 2” white watered silk inside cowl and on outside of cape [f1].

HonPDMusEd: red watered silk, lined grey watered silk, faced 2” white watered silk inside cowl and outside cape [f1].

All other honorary awards except HonFMusICMA (which is unchanged): red watered silk, lined grey watered silk [s1].

1998-

Gowns:

Certificated Teacher (CT,ICMA) DipMus and FDipMus; also HonICMA: Cambridge BA in black stuff [b2].

DASM, PDMusEd and HonFMusICMA: Cambridge MA in black stuff [m2].

Chief Executive: as for 1993-98 rescension.

Hoods:

CT: grey watered silk, lined self-colour, the cowl bound red cord [s1].

DipMus: grey watered silk, lined red watered silk [s1].

FDipMus: grey watered silk, lined red watered silk, faced on all edges with 2” white watered silk [s1].

DASM; PDMusEd: grey watered silk, lined red watered silk, faced 2” white watered silk inside cowl and on outside of cape [f1].

HonICMA: red watered silk, lined grey watered silk, faced on all edges 2” white watered silk [s1].

HonFMusICMA: red watered silk, lined grey watered silk, faced 2” with white watered silk inside cowl and outside cape [f1].

Chief Executive: as for 1993-98 rescension.

Note: a “hire hood” used to cover all diplomas is also used; it is of grey stuff, lined red for earned and red stuff lined grey for honorary diplomas; it is of Aberdeen pattern [a1].

1993-98

Gowns:

CertMus: a black gown of basic Cambridge undergraduate pattern [u2].

DipMus, HonICMA: a black gown of Cambridge BA pattern [b2].

FDipMus, DASM, HonFMusICMA, ProfDipMusEd: Cambridge MA in black [m2].

Chief Executive: a black gown of Cambridge MA pattern [m2] with cherry watered facings. There is a white cord and button on the yoke.

Hoods:

CertMus: grey silk, lined self-colour, bound pink silk, 2” inside and ¼” outside [s1].

DipMus: grey silk, lined white silk, bound kingfisher blue silk, 2” inside and ¼” outside [s1].

FDipMus: grey silk, lined white silk, faced 2” gold silk inside cowl and outside cape [f1].

DASM: as FDipMus, but faced bright cherry watered silk.

ProfDipMusEd: as FDipMus, but faced dark cherry watered silk.

HonICMA: originally red silk, lined grey silk [s1]; later white silk, lined grey silk, faced 2” gold silk on all edges [s1].

HonFMusICMA: white watered silk, lined grey silk, faced 2” gold silk inside cowl and outside cape [f1].

Chief Executive: cherry watered silk, lined white silk, faced 2” grey silk inside cowl and outside cape [f1].

1985-93

Gowns:

CertMus, DipMus, FDipMus: Cambridge BA in black [b2].

AdvDipMus, HonFMusICMA: Cambridge MA in black [m2].

Hoods:

CertMus: gold silk, lined black silk [s1].

DipMus: gold silk, lined black silk, the cowl bound 2” fur [s1].

FDipMus: gold silk, lined red silk, the cowl bound 2” fur [f1].

AdvDipMus: gold silk, lined pale blue silk, cape and cowl bound fur [f1].

HonFMusICMA: gold silk, lined black silk, cape and cowl bound fur [f1].

Note: originally there were also honorary diplomas of HonAICMA, HonLICMA and HonFICMA.

Lancashire College of Music (1935)

Academical Dress

Hood:

LLCM: black lined black, with 2 strips of black, 4” x 36” hanging in front from the join of the neckband and hood, with 2 bands of violet ribbon. The ends of the strips are ‘fishtailed’.

Lancashire College of Music (1986); see North and Midlands School of Music

London Academy of Music

Now part of the North and Midlands School of Music (q.v.)